In July, I had the privilege of presenting at the International Association of Genocide Scholars‘ twelfth meeting in Yerevan, Armenia. The conference’s theme of comparative analysis of twentieth century genocides brought experts from around the world to Armenia’s capital city for five days of presentations, learning, and networking. More than 180 attendees, representing more than two dozen countries, shared their research and insight into many of the twentieth century’s most infamous atrocities.

The conference began on Wednesday, July 8th with a welcome from Armenian President Serzh Sargsyan to attendees. In his address, President Sargsyan discussed the legacy of the Armenian Genocide, not only for the Armenian people, but all of humanity. He also spoke about moving forward, highlighted by his announcement of the creation of a new biannual conference sponsored by the Armenian Republic that will discuss the lasting effects of genocide and how the global community can overcome episodes of violence. A full transcript of President Sargsyan’s address can be found on the Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute’s website.

The conference kicked off Thursday morning with more than 20 breakout sessions exploring themes like prevention, intergenerational trauma, perpetrator justice, and gender and sexuality. I presented research I did this past spring, comparing themes of nationalism in pre-genocide late Ottoman and early American politics. University of Minnesota alumna and current Ohio State sociology professor Dr. Hollie Brehm presented her research analyzing rates of violence at a community level during the Rwandan Genocide.

My favorite session was the cultural genocide breakout. The presentations primarily focused on the continuing destruction and appropriation of Khachkars, ornate stone crosses, and Armenian churches that are scattered across modern Turkey. The presenters brought different and insightful perspectives to the session; an art historian talked about the effect the destruction from an artistic perspective and an Armenian PhD student shared her research from the viewpoint of the Armenian people. There was a great conversation that followed, discussing the limits of the legal definition of genocide versus Raphael Lemkin’s original ideas. The session was moderated by Dr. Adam Muller of the University of Manitoba. Dr. Muller will be visiting the University this fall to discuss his virtual museum project which sheds light on the residential schools for Canada’s First Nations people.

On Thursday evening, we were given a tour of the renovated Armenian Genocide Museum and Tsitsernakaberd, Armenia’s official memorial site. Visiting the museum had a tremendous effect on me. It was a reminder of the human toll of the first genocide of the twentieth century, something I had only experienced through books and documentaries. The museum recently opened its expanded exhibit with new photographs, artifacts, and testimonials in time for the commemorative events marking the 100th anniversary of the genocide. The tour was led by Dr. Hayk Demoyan, the director of the museum and organizer of the conference.

On Thursday evening, we were given a tour of the renovated Armenian Genocide Museum and Tsitsernakaberd, Armenia’s official memorial site. Visiting the museum had a tremendous effect on me. It was a reminder of the human toll of the first genocide of the twentieth century, something I had only experienced through books and documentaries. The museum recently opened its expanded exhibit with new photographs, artifacts, and testimonials in time for the commemorative events marking the 100th anniversary of the genocide. The tour was led by Dr. Hayk Demoyan, the director of the museum and organizer of the conference.

The conference came to an end on Sunday with the unveiling of a stamp by the IAGS executive committee and the Armenian Postal Service, commemorating the conference. Sunday was also Vardavar, the Armenian water festival in which kids toss water on unsuspecting passersby. The soakings made for a refreshing end to an incredible, and hot, conference in Yerevan.

Created in 1994, the International Association of Genocide Scholars is one of the world’s largest groups dedicated to gaining a greater understanding of episodes of genocide and mass atrocities. In 2001, the University of Minnesota hosted the conference. IAGS’ next conference will be in July 2017 in Phnom Penh at the newly opened Sleuk Rith Institute which is Cambodia’s permanent research center dedicated to the Cambodian Genocide.

Joe Eggers is a graduate student at the University of Minnesota, focusing his research on cultural genocide and indigenous communities. His thesis project explores discrepancies between the legal definition and Lemkin’s concept of genocide through analysis of American government assimilation policies towards Native Nations.

The three-day program was opened by the Arsham and Charlotte Ohanessian Lecture, also serving as keynote for the international student conference, delivered by Professor Bedross Der Matossian, University of Nebraska-Lincoln. His talk was titled

The three-day program was opened by the Arsham and Charlotte Ohanessian Lecture, also serving as keynote for the international student conference, delivered by Professor Bedross Der Matossian, University of Nebraska-Lincoln. His talk was titled  The discussions continued the next morning at Ft. Snelling State Park, where Professor Iyekiyapiwin Darlene St. Clair, St. Cloud State University, led a tour of Dakota sites and history connected to both the genesis and genocide of the Dakota people: “Bdote” is the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers, the sacred site of Dakota creation stories and the location of Fort Snelling, where many Dakota were imprisoned and died in in the 1860s.

The discussions continued the next morning at Ft. Snelling State Park, where Professor Iyekiyapiwin Darlene St. Clair, St. Cloud State University, led a tour of Dakota sites and history connected to both the genesis and genocide of the Dakota people: “Bdote” is the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers, the sacred site of Dakota creation stories and the location of Fort Snelling, where many Dakota were imprisoned and died in in the 1860s. Yagmur Karakaya is a PhD student in Sociology at the University of Minnesota. She is interested in collective memory, popular culture and narratives of history. Yagmur is currently working on her dissertation project on Ottomania, which focuses on contemporary interest in the Ottoman past in Turkey. She is interested in how different groups of minorities engage with the ways in which Ottoman past is recalled and how they situate themselves in this narrative. During her Badzin Graduate Fellowship year, she will focus on the commemoration of the Holocaust in Turkey, and the relative silence on the Armenian genocide situating both of these phenomena in the current political interest in the Ottoman past. This project will engage with current debates regarding memorialization and denial in the field of Holocaust and genocide studies within the context of Turkey. She will be focusing on two major non-Muslim minorities in Turkey: the Jewish and Armenian population, conducting interviews with the members.

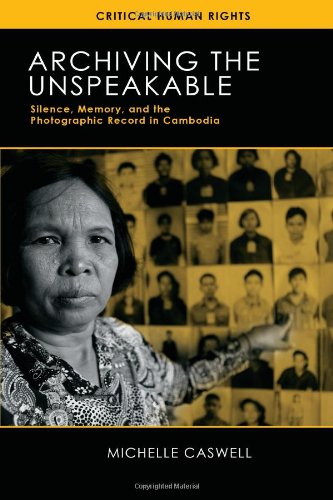

Yagmur Karakaya is a PhD student in Sociology at the University of Minnesota. She is interested in collective memory, popular culture and narratives of history. Yagmur is currently working on her dissertation project on Ottomania, which focuses on contemporary interest in the Ottoman past in Turkey. She is interested in how different groups of minorities engage with the ways in which Ottoman past is recalled and how they situate themselves in this narrative. During her Badzin Graduate Fellowship year, she will focus on the commemoration of the Holocaust in Turkey, and the relative silence on the Armenian genocide situating both of these phenomena in the current political interest in the Ottoman past. This project will engage with current debates regarding memorialization and denial in the field of Holocaust and genocide studies within the context of Turkey. She will be focusing on two major non-Muslim minorities in Turkey: the Jewish and Armenian population, conducting interviews with the members. Roughly 1.7 million people died in Cambodia from untreated disease, starvation, and execution during the Khmer Rouge reign of less than four years in the late 1970s. The regime’s brutality has come to be symbolized by the multitude of black-and-white mug shots of prisoners taken at the notorious Tuol Sleng prison, where thousands of “enemies of the state” were tortured before being sent to the Killing Fields. In Archiving the Unspeakable, Michelle Caswell traces the social life of these photographic records through the lens of archival studies and elucidates how, paradoxically, they have become agents of silence and witnessing, human rights and injustice as they are deployed at various moments in time and space. From their creation as Khmer Rouge administrative records to their transformation beginning in 1979 into museum displays, archival collections, and databases, the mug shots are key components in an ongoing drama of unimaginable human suffering.

Roughly 1.7 million people died in Cambodia from untreated disease, starvation, and execution during the Khmer Rouge reign of less than four years in the late 1970s. The regime’s brutality has come to be symbolized by the multitude of black-and-white mug shots of prisoners taken at the notorious Tuol Sleng prison, where thousands of “enemies of the state” were tortured before being sent to the Killing Fields. In Archiving the Unspeakable, Michelle Caswell traces the social life of these photographic records through the lens of archival studies and elucidates how, paradoxically, they have become agents of silence and witnessing, human rights and injustice as they are deployed at various moments in time and space. From their creation as Khmer Rouge administrative records to their transformation beginning in 1979 into museum displays, archival collections, and databases, the mug shots are key components in an ongoing drama of unimaginable human suffering. Holocaust Archaeologies: Approaches and Future Directions aims to move archaeological research concerning the Holocaust forward through a discussion of the variety of the political, social, ethical and religious issues that surround investigations of this period and by considering how to address them. It considers the various reasons why archaeological investigations may take place and what issues will be brought to bear when fieldwork is suggested. It presents an interdisciplinary methodology in order to demonstrate how archaeology can (uniquely) contribute to the history of this period. Case examples are used throughout the book in order to contextualize prevalent themes and a variety of geographically and typologically diverse sites throughout Europe are discussed. This book challenges many of the widely held perceptions concerning the Holocaust, including the idea that it was solely an Eastern European phenomena centered on Auschwitz and the belief that other sites connected to it were largely destroyed or are well-known. The typologically, temporally and spatial diverse body of physical evidence pertaining to this period is presented and future possibilities for investigation of it are discussed. Finally, the volume concludes by discussing issues relating to the “re-presentation” of the Holocaust and the impact of this on commemoration, heritage management and education. This discussion is a timely one as we enter an age without survivors and questions are raised about how to educate future generations about these events in their absence.

Holocaust Archaeologies: Approaches and Future Directions aims to move archaeological research concerning the Holocaust forward through a discussion of the variety of the political, social, ethical and religious issues that surround investigations of this period and by considering how to address them. It considers the various reasons why archaeological investigations may take place and what issues will be brought to bear when fieldwork is suggested. It presents an interdisciplinary methodology in order to demonstrate how archaeology can (uniquely) contribute to the history of this period. Case examples are used throughout the book in order to contextualize prevalent themes and a variety of geographically and typologically diverse sites throughout Europe are discussed. This book challenges many of the widely held perceptions concerning the Holocaust, including the idea that it was solely an Eastern European phenomena centered on Auschwitz and the belief that other sites connected to it were largely destroyed or are well-known. The typologically, temporally and spatial diverse body of physical evidence pertaining to this period is presented and future possibilities for investigation of it are discussed. Finally, the volume concludes by discussing issues relating to the “re-presentation” of the Holocaust and the impact of this on commemoration, heritage management and education. This discussion is a timely one as we enter an age without survivors and questions are raised about how to educate future generations about these events in their absence. with ‘Save Darfur’ emblazoned on them. Syria, Iraq, Liberia, South Sudan, and Central Africa Republic have overtaken Darfur in the attention sweepstakes in the news. In previous posts I have talked about Compassion Fatigue and the four horsemen of the apocalypse whenever atrocities were covered in the media. However, when is it ok to say enough is enough? When do we, as global citizens, stop shaking our heads and going “tsk tsk, it is so sad what is happening in that country”? These are questions I have asked myself over the past few years. As a graduate student, I have often wondered if my keeping an eye on Darfur is influenced by the fact that my research is in the region. Would it matter as much if my research was on, say, farming practices in Africa? I would like to think it would, if for no reason other than the fact that my country (Kenya) shares a border with South Sudan. I would like to think that whenever I opened the local daily at a coffee shop, or on my way to work in the morning, I would read the news about Darfur and seek out like-minded individuals to try and help in some way, shape or form. What form of help this would be I’m not sure as of yet. So to the question, what have I done for Darfur lately? My honest answer is not as much as I would have liked to do. As Darfur has morphed into a conflict occurring in the shadows (a dreadful prospect) my sense of hopelessness has also increased. What will your answer be?

with ‘Save Darfur’ emblazoned on them. Syria, Iraq, Liberia, South Sudan, and Central Africa Republic have overtaken Darfur in the attention sweepstakes in the news. In previous posts I have talked about Compassion Fatigue and the four horsemen of the apocalypse whenever atrocities were covered in the media. However, when is it ok to say enough is enough? When do we, as global citizens, stop shaking our heads and going “tsk tsk, it is so sad what is happening in that country”? These are questions I have asked myself over the past few years. As a graduate student, I have often wondered if my keeping an eye on Darfur is influenced by the fact that my research is in the region. Would it matter as much if my research was on, say, farming practices in Africa? I would like to think it would, if for no reason other than the fact that my country (Kenya) shares a border with South Sudan. I would like to think that whenever I opened the local daily at a coffee shop, or on my way to work in the morning, I would read the news about Darfur and seek out like-minded individuals to try and help in some way, shape or form. What form of help this would be I’m not sure as of yet. So to the question, what have I done for Darfur lately? My honest answer is not as much as I would have liked to do. As Darfur has morphed into a conflict occurring in the shadows (a dreadful prospect) my sense of hopelessness has also increased. What will your answer be? The symposium opened with a

The symposium opened with a nature of the field of transitional justice. Its assumptions, its philosophical sources and allegiances, its methodological orientations, and most of all, its understanding of how the past exists in, living through the present. Dr. Ryan Molz addressed the lustration policies in Macedonia, Croatia and Serbia, arguing that each of the states had a differing level of implementation of this vetting process due to internal factors, while external factors, such as the international community, have largely been unsupportive of lustration policies. Later, Prof. Adam Czarnota addressed the tension between a demand for formal “rule of law” in countries in transition and the realities of lived memory and informal rule of law already existing in the states. Czarnota noted that there is often a “supply of law”, but no matching demand in transitional contexts. Finally, Prof. Nadya Nedelsky spoke about Slovakia’s struggle with its past, pointing out that societal and academic discourse often do not intertwine on the ground, leading to deeply problematic issues, such as the downplaying of the Nazi-aligned state of the 1930s.

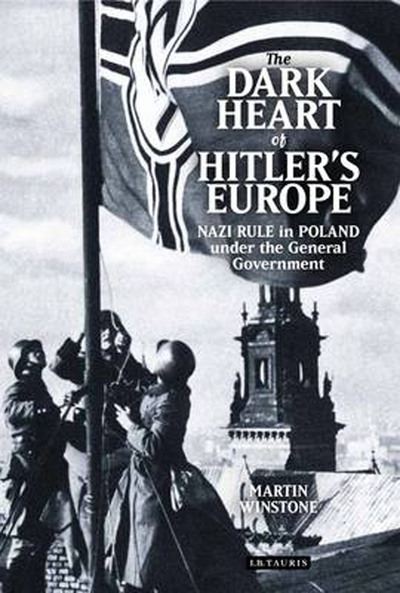

nature of the field of transitional justice. Its assumptions, its philosophical sources and allegiances, its methodological orientations, and most of all, its understanding of how the past exists in, living through the present. Dr. Ryan Molz addressed the lustration policies in Macedonia, Croatia and Serbia, arguing that each of the states had a differing level of implementation of this vetting process due to internal factors, while external factors, such as the international community, have largely been unsupportive of lustration policies. Later, Prof. Adam Czarnota addressed the tension between a demand for formal “rule of law” in countries in transition and the realities of lived memory and informal rule of law already existing in the states. Czarnota noted that there is often a “supply of law”, but no matching demand in transitional contexts. Finally, Prof. Nadya Nedelsky spoke about Slovakia’s struggle with its past, pointing out that societal and academic discourse often do not intertwine on the ground, leading to deeply problematic issues, such as the downplaying of the Nazi-aligned state of the 1930s. Even amidst the horrors of Nazi rule in Europe, the tragic history of the General Government – the Nazi colony created out of the historic core of Poland, including Warsaw and Krakow, following the German and Soviet invasion of 1939 – stands out. Separate from but ruled by Germany through a brutal and corrupt regime headed by the vain and callous Hans Frank, this was indeed the dark heart of Hitler’s empire. As the principal ‘racial laboratory’ of the Third Reich, the General Government was the site of Aktion Reinhard, the largest killing operation of the Holocaust, and of a campaign of terror and ethnic cleansing against Poles which was intended to be a template for the rest of eastern Europe.

Even amidst the horrors of Nazi rule in Europe, the tragic history of the General Government – the Nazi colony created out of the historic core of Poland, including Warsaw and Krakow, following the German and Soviet invasion of 1939 – stands out. Separate from but ruled by Germany through a brutal and corrupt regime headed by the vain and callous Hans Frank, this was indeed the dark heart of Hitler’s empire. As the principal ‘racial laboratory’ of the Third Reich, the General Government was the site of Aktion Reinhard, the largest killing operation of the Holocaust, and of a campaign of terror and ethnic cleansing against Poles which was intended to be a template for the rest of eastern Europe. Utjiua Muinjangue is the chairperson of the Ovaherero and Ovambanderu Genocide Foundation. Ms. Muinjangue spoke on behalf of the school of Social Work at the University of Minnesota on the genocide of the Herero on November 10, 2014.

Utjiua Muinjangue is the chairperson of the Ovaherero and Ovambanderu Genocide Foundation. Ms. Muinjangue spoke on behalf of the school of Social Work at the University of Minnesota on the genocide of the Herero on November 10, 2014.