In 2019 I attended a summer workshop for teachers held by the CHGS, titled “Teaching About Genocide.” As part of the workshop, we, along with two Native American activists-teachers, toured the Minnesota State Capitol with a docent. Entering the main chamber of the capitol, our guide gestured toward several portraits of white males who colonized Minnesota. She, an employee of the state, noted they were the men “who discovered Minnesota.” Here, in the most prominent institution of Minnesota government, a guide had normalized colonialism, except the normalization was now being heard by a critical audience. The statement seemed bracingly out of step with our appreciation of multiculturalism, the celebration of ethnic and racial diversity, and acknowledgment of the centrality of indigenous peoples to the shared fabric of American history.

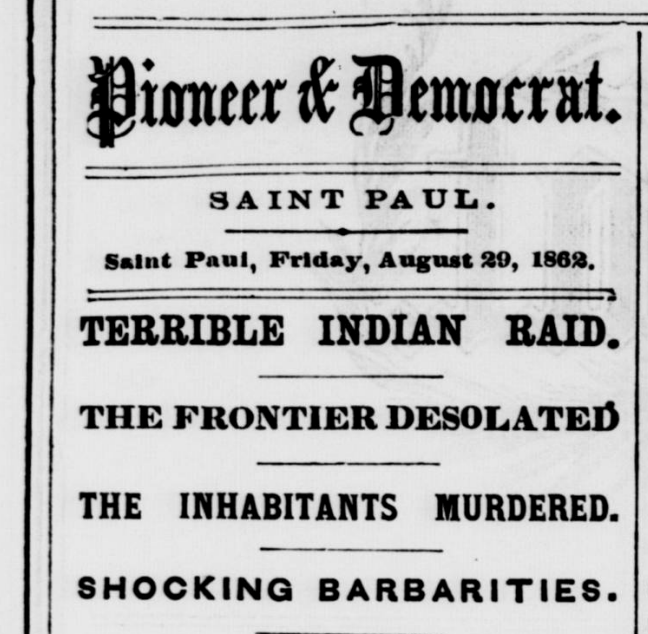

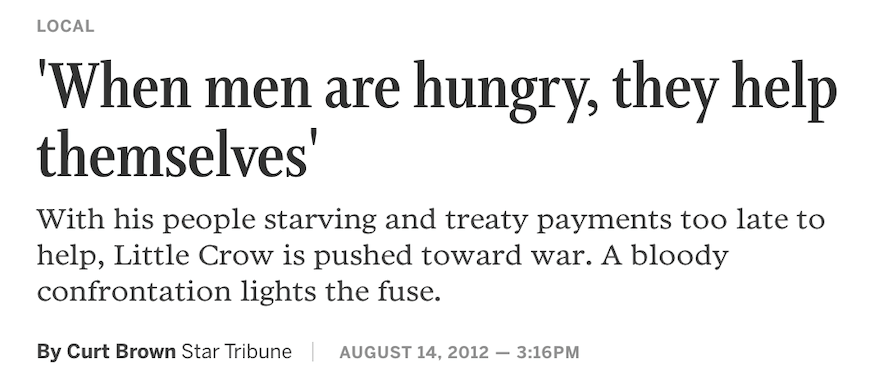

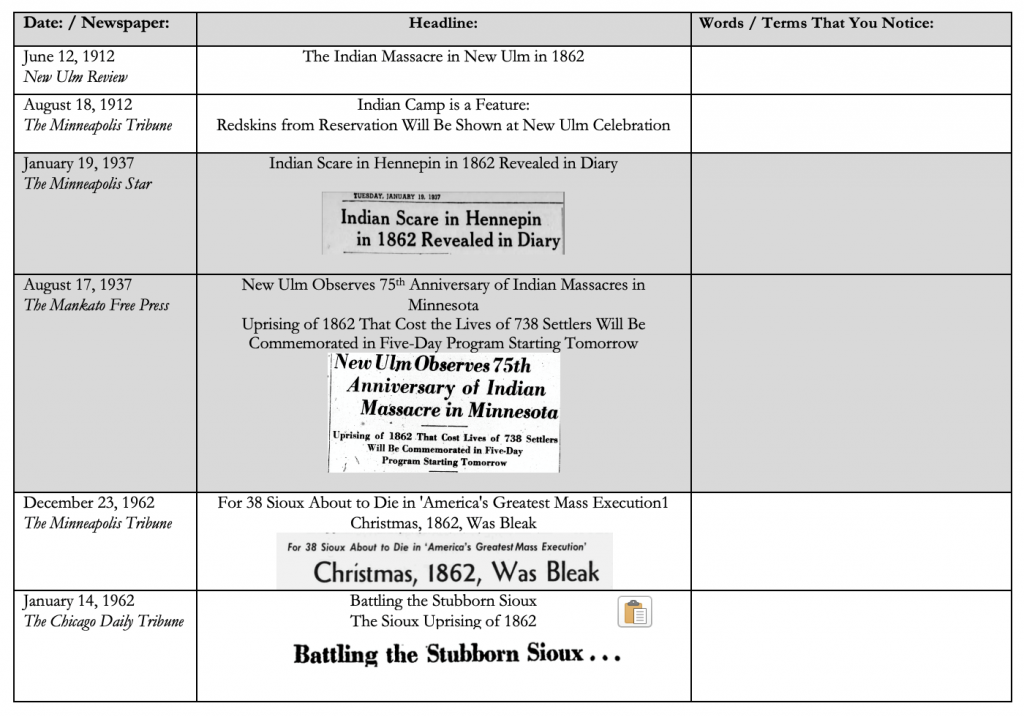

Our workshop helped us, as teachers activate new schemas for understanding colonialism in America. In psychology, a schema is a pattern of thinking organizing categories of information. In one workshop presentation, George Dalbo and Joe Eggers discussed “settler colonialism.” They used the concept as a framework for analyzing historical processes, in particular, the colonialization of indigenous people and land in Minnesota. Dalbo and Eggers noted that settler colonialism involves three stages: removing indigenous peoples, replacing them with settlers, and continually renewing and normalizing such colonialization. The workshop helped me develop a new schema. I spent the rest of the summer considering the continual renewal and normalization of colonialization. In particular, I began seeing how settler colonialism is made both visible and invisible in everyday life.

Visiting Duluth later that summer, I went to a prominent city park. There I saw a statue of Leif Erikson, which, an inscription said, was sponsored and erected by the Norwegian American League in 1956. After Erikson’s name was the statement, “discoverer of America.” Although there seemed to be attempts at darkening that phrase to be less legible, I saw both how normalizing such a statement otherwise was, and how transparent it was to anyone knowledgeable of settler colonialism. Yet here, the statue and statement stood in 2019, without any information qualifying or contextualizing it.

As Patrick Wolfe (2006) phrased it, “settler colonialism destroys to replace.” Regarding my focus here on monuments, there have been several recent debates about Civil War monuments as celebrations of slavery and racism, and how some feel those monuments should be either removed or contextualized through other plaques, information, or additional monuments. The monuments I saw over the summer celebrating settler colonialism, though, did not seem to be causing much debate. Instead, they seemed to be evidence of the normalization of colonialism, particularly central in Nebraska. One such bronze statue served to minimize the importance of indigenous histories, instead offering settler replacements and framings.

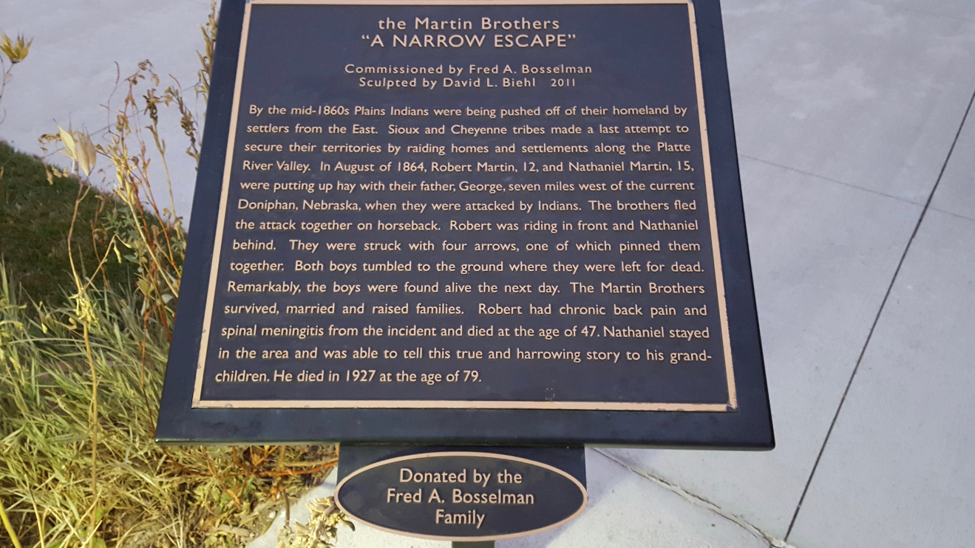

Returning to my hometown of Kearney, Nebraska, I focused on a prominent bronze statue at the entrance to the Archway Monument, a prominent tourist attraction on Interstate 80. The statue corresponds to a story told on a nearby plaque, titled “the Martin Brothers ‘A Narrow Escape.’” The statue and plaque commemorate an incident—in 1864, two children of white settlers who were riding a horse seven miles from Doniphan, Nebraska, had been “attacked by Indians,” having been “struck with four arrows,” and “left for dead,” but had survived to tell the “true but harrowing tale.” The phrasing on the plaque is noteworthy—besides the use of the term “Indians,” the plaque notes that Sioux and Cheyenne tribes were trying to “secure” their land. The plaque might have a different spin if, say, the word “defend” was to replace “secure.”

Through the schema of settler colonialism, other questions about the statue and plaque might emerge: what peoples here are depicted as being attacked? How does an understanding of colonialists as colonialists seem to grow distorted when a statue emphasizes their children as victims of an unprovoked attack? What is the background of those who created the statue? And what is the background of those donating the statue? The statue was made by Dr. David L. Biehl and commissioned by Fred A. Bosselman, both from farming families in Nebraska. Bronze copies of Biehi’s statue are also prominently displayed in central Nebraska at the Stuhr Museum of the Prairie Pioneer in Grand Island, and the Hastings Museum in Hastings (Pore 2012). Fred A. Bosselman, whose family donated the statues, is the founder of Bosselman Truck Plaza in Grand Island. Bosselman Enterprises now owns forty-five Pump & Pantry convenience stores across several states (Bosselman Enterprises 2020).

It makes sense that settlers and their descendants want to celebrate their history, endowing museums and public parks with statues depicting legendary stories and heroes. The problem comes when those statues are prominently displayed at state-sponsored institutions at the expense of other accounts and contextualized histories that would allow visitors also to consider settler colonialism. Simple public acknowledgments of settler colonialism alongside such statues, such as those discussed here, would be a seemingly small, but perhaps important, step toward repairing the dominant group’s relations with indigenous Americans. Such public acknowledgments might also help improve and add complexity to the knowledge citizens have of their country. Such acknowledgments might also perhaps address the guilt that surely underlies bald attempts at erasing and replacing the histories of peoples devastated by colonialism.

Kurt Borchard, Ph.D., is a Professor of Sociology at the University of Nebraska Kearney, where he teaches a course on the Holocaust. He has written extensively about cultural studies and homelessness.

Biehl, David L. 2013. The Martin Brothers. Lincoln, NE: Prairie Muse Books.

Bosselman Enterprises. 2020. Company History. Online. Available: https://www.bosselman.com/history/

Pore, Robert. 2012. Hall County History Comes to Life as Statue Dedicated at Stuhr Museum. The Independent (Grand Island). 6 July.

Wolfe, Patrick. 2006. Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native. Journal of Genocide Research 8(4):387-409.