The recent protests in response to the murders of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd in our own Minneapolis, coupled with the spread of Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests across the globe, have sparked a much-needed conversation within the field of Genocide Studies. The BLM movement calls for the end of anti-Black racism in the United States (and around the globe), and the movement has shined a light on an American legacy of systemic racism — or racism that is ingrained within our social, cultural, and political institutions.

As genocide scholars we know systemic racism. The United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination’s Declaration of the Prevention of Genocide has emphasized genocide’s connection with systemic racism, calling for the prevention of “persistent patterns of racial discrimination and other systemic violations of human rights that could lead to violent conflict and genocide.” We know that one of the critical early warning signs of genocide is a legacy of discrimination and persecution.

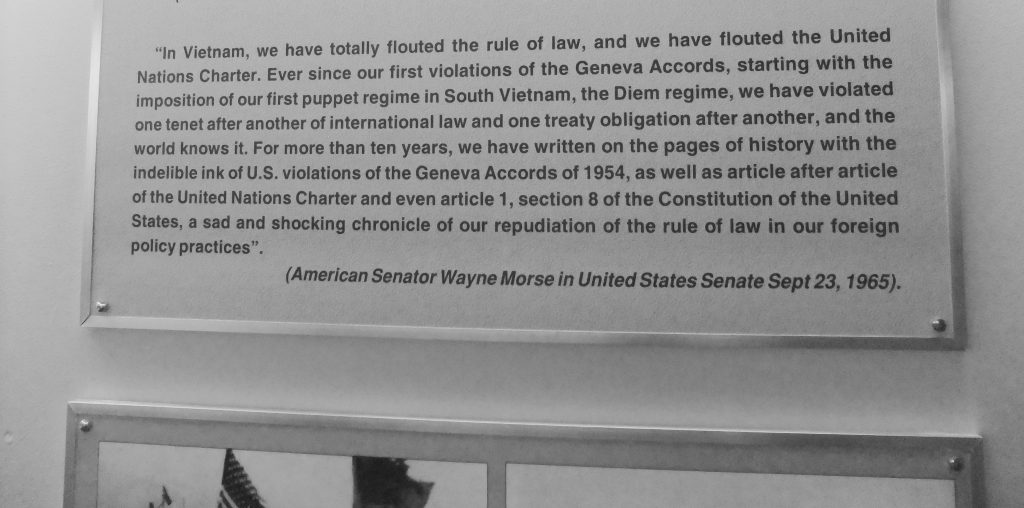

As genocide scholars, we have explored the origins and consequences of violence. We have looked at the historical, or rather modern, roots of racism (Weitz 2003), and how ordinary citizens and law enforcement officers are mobilized into extreme forms of violence (Browning 1992). We have learned how governments and individuals legitimize violence, often using fear to justify their actions (Straus 2006). We have learned about the banality of evil (Arendt 1964) and how seemingly neutral organizations can participate in mass violence (Kühl 2016). We have learned that just because a violent act is legal, doesn’t mean it is moral.

Classic social theorist, Max Weber (1946), defined the state by its monopolization on the legitimate use of violence. He argued that the state can protect its citizens from violence and commit violence against them or the citizens of other states. Yet in the era following WWII, the right of the state to perpetuate violence against its own people (particularly unarmed civilians) was questioned by the international community. As genocide scholars have discussed, Hitler’s murderous campaign against the Jews was not illegal, and while norms were certainly changing during this time, genocide was not an established crime (Savelsberg 2010).

It is only more recently, with the development and globalization of human rights and humanitarian law, that state sovereignty has begun to diminish. As a result, episodes of mass violence committed by states against their own populations are increasingly becoming understood and tried as crimes. We have seen this with the creation of the International Criminal Tribunals for both Rwanda (1994-2015) and the Former Yugoslavia (1993-2017). More recently, we have seen this with the International Criminal Court’s involvement with Darfur (2005) and the International Court of Justice with Myanmar (2019).

Yet, due to the extreme nature of genocide, scholars are often hesitant to explore and comment on other forms of violence that do not amount to genocide. But in doing so, we risk turning a blind eye to the various forms of ongoing violence being committed in countries such as the US. As those who understand violence to its most heart-wrenching detail, it is our responsibility to share our knowledge and speak out against the injustices happening in our own communities.

While it is never easy to study genocide, it is much easier to study violence when you are removed from it. As a result, scholars like myself often study episodes of mass violence that are either historically or geographically removed from our own lives. However, the knowledge from this field can and must be used to explore and critically analyze American history and White violence against Black Americans. CHGS will contribute to this conversation through a series of articles that discuss contemporary and historical forms of violence in the US in our series entitled: Anti-Black Violence in the US.

In this series we at the Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies will explore the connection between social movements and genocide, share photo essays from Black Lives Matter Protests around the country, and interrogate the violence being perpetrated against Black Americans. It is with this series that our blog will turn inwards, exploring our own backyard and the violence being committed here. It is our hope that this series will begin to explore both what our field can learn from the Black Lives Matter movement and the horrific death of Minneapolis resident, George Floyd and what we may contribute.

Jillian LaBranche is a Ph.D. Candidate in Sociology and a Research Assistant at the Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies at the University of Minnesota. Her research interests broadly include violence, knowledge, collective memory, and comparative methods. Her research seeks to understand how societies that recently experienced large-scale political violence teach about this violence to the next generation.