Genocide studies

To interpret images of genocide consequently involves a double competence, which puts genocide specialists (historians, anthropologists, sociologists, psychologists, among others) and image analysts (semiologists, film or photography historians, new media specialists) in a separately delicate situation. The task demands the command of theory and methods within multiple scholarly fields, including specific instruments for the analysis of visual texts. The question continues to be: what can the image contribute –as iconography and as a visual narrative– to the comprehension of genocide and mass violence that could not be gained from other available documents which were traditionally studied by the discipline of history. This is a

To probe this question my colleague Vicente Sánchez-Biosca, and I have curated a special issue of the International Association of Genocide Scholars’ journal dedicated to the exploration of images in genocide studies – with a special focus on memory – and its methodological considerations.

“You Could See Rage”: Visual Testimony in Post-genocide Guatemala by Lacey M. Schauwecker. The author analyses the link between narrative and audio-visual testimonies to study the Guatemalan genocide, using the notions of visuality and countervisuality. In this context, she examines how survivor Rigoberta Menchú and performance artist Regina José Galindo utilize the testimony to express rage. Thereby, Schauwecker associates this type of testimony with the witnesses’ right to testify on their own terms beyond institutional processes and imperatives.

Nineteen Minutes of Horror: Insights from the Scorpions Execution Video by Iva Vukušić is the third article. In there, the author notes that the video recorded by the Scorpion unit during the Srebrenica genocide in the summer of 1995, provides unique insights into the nature of the crime, as well as the behavior of the perpetrators, and it constitutes a significant contribution to our knowledge of the events.

Christophe Busch’s article focuses on photographs taken by Nazi perpetrators. In Bonding Images: Photography and Film as Acts of Perpetration the author analyses how photography is utilized to create an in-group, noting that, as images are performative, the imagery bound the in-group.

The figure of the perpetrator is also analyzed by Ana Laura Ros in her analysis of the documentary film El Mocito. In her article El Mocito: A Study of Cruelty at the Intersection of Chile’s Military & Civil Society. The author argues that the film poses questions about responsibility for, and complicity with, the cruelty that took place during the military regime and beyond, which all members of Chilean society must consider.

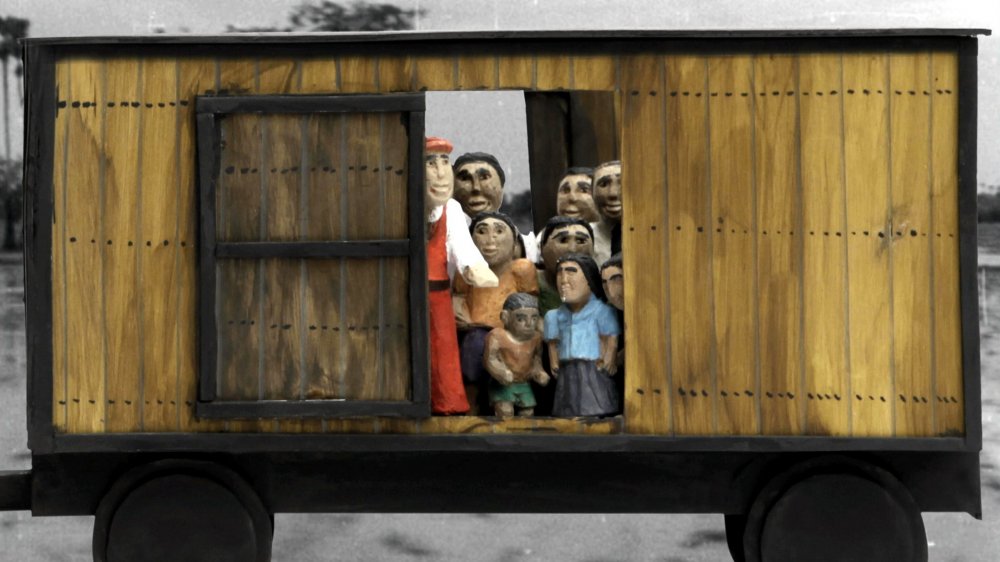

In Vicente Sánchez-Biosca’s article, Challenging Old and New Images Representing the Cambodian Genocide: ‘The Missing Picture’, the author examines the film “L’image Manquante” by Rithy Panh to highlight the way in which the French-schooled Cambodian director approaches the classical question inherited from the Holocaust of the non-representability of a genocide.

In Cockroaches, Cows and “Canines of the Hebrew Faith”: Exploring Animal Imagery in Graphic Novels about Genocide, Deborah Mayersen suggests that graphic novels about genocide feature a surprisingly rich array of animal imagery. While there has been substantial analysis of the anthropomorphic animals in Art Spiegelman’s Maus, Mayersen argues that the roles and functions of non-anthropomorphized animals have received scant attention. In this vein, in her article she carries out a comparative analysis of ten graphic novels about genocide to identify and elucidate the archetypical functions of nonanthropomorphized animals.

Nora Nunn’s article, The Unbribable Witness: Image, Word, and Testimony of Crimes against Humanity in Mark Twain’s King Leopold’s Soliloquy (1905), studies the crimes committed in the Belgian Congo Free State through the work of Mark Twain. The author suggests that this text aimed to evoke its Euro-American audience’s empathy by activating their imaginations. In this way, Nunn considers how the visual imagery in Twain’s text engenders questions about fact, testimony, and witnessing in the realm of human rights and mass violence

The final article, Memory

I encourage you to view the special issue of the journal and continue to explore the significance and role of images in genocide and mass violence studies. Our edited volume of Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal was published last year, and is freely accessible through the International Association of Genocide Scholars website.

Lior Zylberman has a Ph.D. in Social Sciences (UBA), is a professor of Sociology (UBA) and a researcher at the CONICET (National Scientific and Technical Research Council) and at the Center for Genocide Studies (UNTREF). His research topic is the representation of genocides in documentary film and he has published numerous articles on the subject.

Comments