Daniel Reynolds is the Seth Richards Professor in Modern Languages at Grinnell College in Grinnell, Iowa. His works

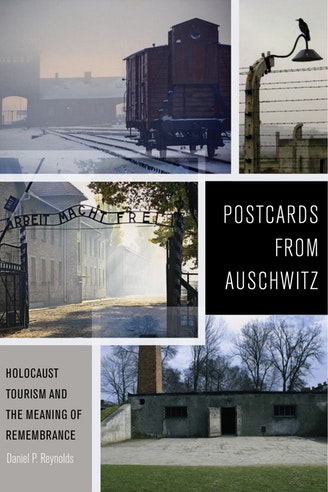

In November, the Center for Holocaust & Genocide Studies welcomed Dr. Reynolds for a lecture where he touched on the themes of his latest book and Holocaust tourism’s effect on how we remember.

Kathryn Huether: I wanted to start with Michael Rothberg’s text regarding migration and the Turkish immigrant in Germany, in your book you discuss the distinction between a Holocaust tourist and pilgrim, and it just reminded me of the “double paradox” that Michael Rothberg highlights. Could you speak more of your distinction between the pilgrim and tourist?

Daniel Reynolds: Yes, I guess I would be sure to say that it is a distinction but not

Right. Yes. And do you think that perhaps certain sites are more conducive to that—because certainly, Auschwitz-Birkenau is where most people go…but sites such as Treblinka offers much more reflection, but it is harder to get to?

Yes, it is harder to get to. And I think that it is definitely a part of it. When I think of pilgrimage, it’s funny, when I think of sites of pilgrimage I think of Bethlehem and the Church of Nativity which gets packed with people. There are ways in which sites that we think of as typical destinations of pilgrimage actually highlight some of the more unpleasant attributes of tourism that we criticize, i.e. the crowds. But yea, I would agree that different sites lend themselves to more reflective experiences. I think Treblinka for me was very moving, and Belžec, of

That’s great. I wanted to bring it back to your book and much of your argument is based on this concept that you call phenomenology of tourism. Could you speak more of that?

So phenomenology of tourism, I’m not a trained ethnographer—I don’t have tons of interviews with tourists that I’ve conducted and I don’t have a method for quantifying anything experientially…I am not so interested in showing how some tourists feel one way versus how many think the other way. I am more interested in demonstrating the range of possibilities for responses. And I think phenomenology, which is how we come to know of the world, not just through logic and rational thought, but also through sensory perception and affect [, in relation] to tourism is always an embodied encountered in space. So you’re always experiencing the site

I agree—it’s very close to what I’m working on now. And I wanted to push this a bit further, you focus your phenomenological reading on the visual, and of course there are multiple senses that are impacted—last summer I was able to visit the preservationist department at Auschwitz-Birkenau with my fellowship group from the Auschwitz Jewish Center, and the preservationists dedicate a large part of their efforts to preserving objects such as shoes, suitcases, shoes, toothbrushes, etc.—but this act of preservation is strongly connected to the visual, and one of the preservationist said that within fifteen years “this toothbrush will be gone, this suitcase deteriorated.” And, I feel a bit dark saying this, but one of my colleagues asked, “what are you going to do with the human hair when that is gone as well?” Are you going to replace it with fake hair, for instance as the infamous gate that reads “Arbeit Macht Frei” is no longer the original, replaced after the original was stolen—so, is there something about the “authenticity” of the object that needs to be present, juxtaposed to sites such as Treblinka, when the materiality and object centered preservation is nonexistent? How is the visual of Treblinka, for instance, different from that of Auschwitz-Birkenau?

That’s great, yea, that touches on a lot of things…the ephemerality of

Yes, but even then, the presentation of the exhibits is very curated. The room with the shoes, the coloring is very specific, organized so that a pristine red heel sits on the top, you can see children’s shoes right up front…

Yes, yes that they are an assemblage—that is very important to acknowledge. And I know that the hair is treated with certain chemicals so that it is preserved longer…Yea, I think that probably, these sites are going to have to find another way to convey what they are trying to convey. The image that is largely associated with Holocaust sites is the thousands of shoes, and I sometimes think that

No, no, that’s okay. Do you think that perhaps the emphasis placed on preserving these objects, I don’t want to say takes away from, I don’t want to say “better presentation,” but like at Auschwitz there are so many people there and everyone is walking around with headphones over their ears and it is so crowded. It is the actual site itself, but perhaps there is a more effective way of presenting that without millions of people at the site?

Yea, I think maybe what this gets at, is that there are two impulses in this museum curation. First, what is an aesthetic choice, what makes the best arrangement of

Yes, so continuing off of that, with the graduate students we were talking about the Jewish Museum in Berlin and POLIN—Museum of Polish Jews in Warsaw, and you stated that you thought POLIN was more effective, but also I think it’s really interesting because Berlin has actual artifacts and POLIN does not, given the history of Polish Jewry and such, but could you speak more to that distinction and your preference for POLIN?

Okay, so it’s been a few years since I’d been to POLIN, and I was happy to hear your response to it, so I have a reason to go back. You know, I think that the building in Berlin is a really powerful space—the architecture is wonderful.

Did you use an audio guide by chance?

I did, and of course I didn’t follow it step by step, but I used it at both museums.

Yea, I don’t think most people follow it.

I wasn’t well versed in Polish Jewish history, so I think I learned something—but I was just really impressed by the space, and

Right, it was made to be one…in its mission, Daniel Libeskind designed it to reflect the Holocaust.

Right, it’s hard to be both. And some might say that perhaps that is how the museum is effective, because it is jarring.

That’s kind of what I argue, yes, that it is because you don’t really settle on either end…

Yes, I think I would just like the museum directors to be more direct about the fact that it is both.

Oh, I agree, they did actually change the audio guide, and I think this incorporates the narrative more. But back to POLIN, I also used the audio guide, and I did not have a contemplative experience, I thought the sound was overwhelming, but of course, that’s what I’m paying attention to specifically.

Yea, I need to go back. It’s not like the thumping heartbeat of Warsaw at the Warsaw Rising Museum.

Did you listen to it really closely? Because each strand is supposed to be a distinctive song from wartime Poland.

Fascinating, yet that museum is filled with points of inquiry.

But I wanted to bring it back once again to the sensorially aspect, and to Treblinka, which doesn’t have the materiality of Auschwitz-Birkenau. And presently, a visitor can download an audio guide from the app “AudioTrip,” which I think adds an acoustic architecture, a materiality of sorts.

[Listen to segments of the audio guide here]

Yea, I think that certainly takes away from the experience. I was not fond of the fake wind whistling through the barren landscape—that’s not what you experience, particularly if you go there in the summertime, which has lush trees and green grass. And the idea that you would have manufactured forest sounds, and block out the real forest sound, doesn’t make sense to me. I think that

Kathryn Agnes Huether is a Ph.D. student in Historical Musicology with a Graduate Minor in Cultural Studies at the University of Minnesota. Her dissertation research is an extension of her work on Holocaust memory and sonic

Comments 1

LouAnn Atkinson — April 29, 2019

What an insightful interview conducted by Kathryn Huether. She was able to bring so many observations to the vanguard through the discussion with Daniel Reynolds. I am sure the experiences at many of the Holocaust sites will change significantly in years to come, especially for tourists and pilgrims who visit, as a result of this interview.