In this interview with Yagmur Karakaya, Prof. Olick demystifies processes involved in collective memory, discusses the role of emotions and nostalgia in remembrance, and introduces the notion of regional constellations of memory. Olick also untangles the fruitful concept of “legitimation profiles”, which he applies in his latest book to the ways Germany confronts the specters of its Nazi past.

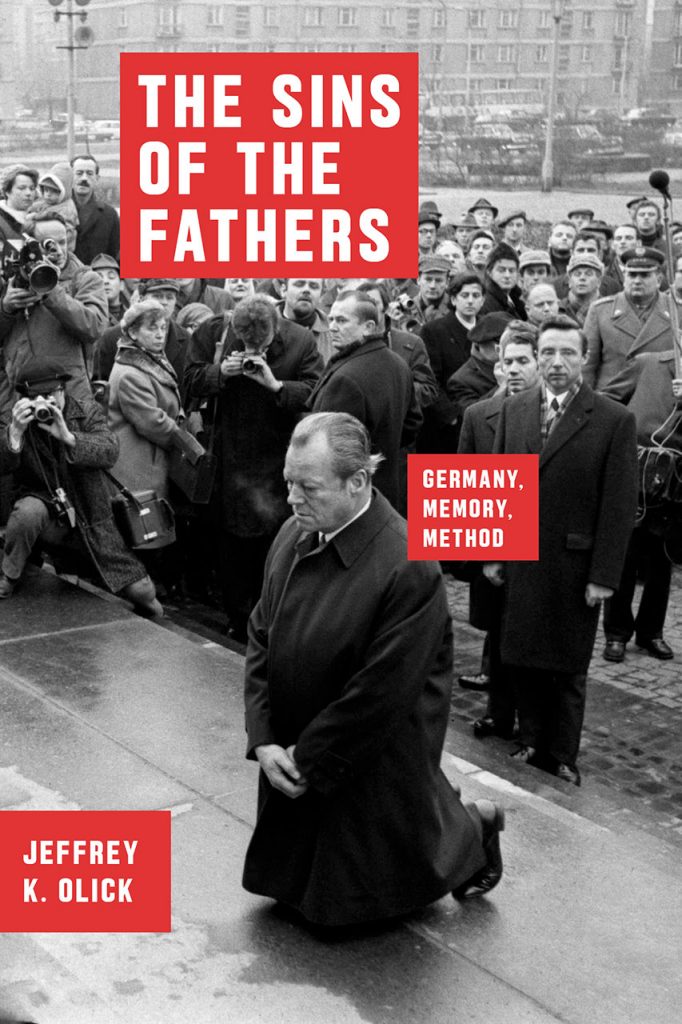

Jeffrey Olick is a professor of sociology and history and chair of the sociology department at the University of Virginia. He is a cultural and historical sociologist whose work has focused on collective memory and commemoration, critical theory, transitional justice, postwar Germany, and sociological theory more generally. His books include “The Politics of Regret: On Collective Memory and Historical Responsibility,” and “The Sins of Fathers: Germany, Memory, Method”.

(Editor’s note: This is a condensed version of our interview with Dr. Olick. Follow the link at the end to read the interview in its entirety.)

In your work, you introduce concepts that disentangle the often mystified term ¨collective memory.¨ Can you elaborate on those?

Collective memory tends to imply that there’s one collective memory that everyone shares or that collective memory is this mystical group mind. And I don’t think of it that way. So in my own work, I refer to what I call “mnemonic practices” practices and also “mnemonic products” and “mnemonic processes.” And there are wide numbers of different mnemonic practices, and products, and processes. So for instance, remembering your phone number is a particular kind of mnemonic practice. Remembering who the president is is another one. Remembering that time we went on a hike is yet a different one. Remembering that America had a civil war is yet a different one. So is giving a speech or painting a painting about the past, or telling a story, or recalling a set of numbers and facts. These are all different mnemonic practices. The question from memory studies is how they relate to each other or don’t. There’s also a variety of mnemonic products. You know, a statue is a mnemonic product. A historical movie is a mnemonic product. An essay is a mnemonic product; so is a story I might tell at a dinner table. These are different mnemonic products. The question is, how are they, in the words of media scholars, how are they intermedial? How does the telling of the story at the dinner table, affect people’s experiences and the way in which a museum is constructed? So the question is how do all of these different mnemonic products, practices, and processes relate to each other? Which is, I think, a more differentiated way of speaking about the many things that constitute what we label with the term collective memory.

So, I have a “personal interest” where do you see emotions in all this? Like where do you see and how do you think we can theorize in emotions into this interaction between individual and collective memory or mnemonic practices?

So I would say, first of all, that memories preserve emotions and can call up emotions in interesting and complex ways. So that, for instance, remembering something that angered you in the past, can make you angry again. Emotion also feeds into the ways in which we decide something is worth remembering. The notion of the trope in politics, particularly the politics of genocide, “Never Forget.” That implores us, it demands us, it demands something of us, it riles us up, it creates a strong sense of obligation. So emotions feed into both what we remember and memory feeds into and creates emotions when we do remember. One of the interesting things though is the ways in which both memory and emotion can be separate. So I can remember that I was really angry at my partner or my kid or something like that, but I’m not angry anymore about it. I can remember that I was, but it’s gone away. I remember what caused it, and isn’t it strange that I was so angry at the time, but I don’t feel that anger anymore. By the same token, I can remember the feeling of anger sometimes. I wake up (this is a terrible thing to say about myself), sometimes I wake up angry and I can’t put my finger on what it is I’m angry about… So these work in complex ways, but I should also point out that so much of the discussion in memory studies is about trauma, and negative memories, and outrage, and things like that. There’s also memories of joy and happiness. It’s very important in certain circumstances to hold onto positive memories; that something actually worked really well or was really nice. Of course, the one lesson of a long life is that it’s very hard, you can’t step in the same river twice, that even something you remember as great, may not have been all that great in fact. So this is one of the distortions of nostalgia, which is an emotional distortion. You venerate a past and you load extra emotions onto a past that may or may not have been actually a part of the process in the first place.

In your book “The Sins of the Fathers” you develop a new concept, legitimation profiles. Can you explain it for us, and talk about its applicability to different cases?

The Sins of the Fathers is organized on two analytical principles: profile and genre.

In recent talks, you have introduced the concept of “regions of memory”. How does it fit within the overall trend of

There’s been an argument about, with the mass media and the worldwide knowledge about certain historical events, there’s been

Find the complete interview here.

Yagmur Karakaya is a

Comments