A new article reports the findings from a longitudinal study that followed 667 women who had early- and later-term abortions for three years after their procedure. Dr. Corinne Rocca and her colleagues asked women if they felt that the abortion was the “right decision” at one week and approximately every six months thereafter.

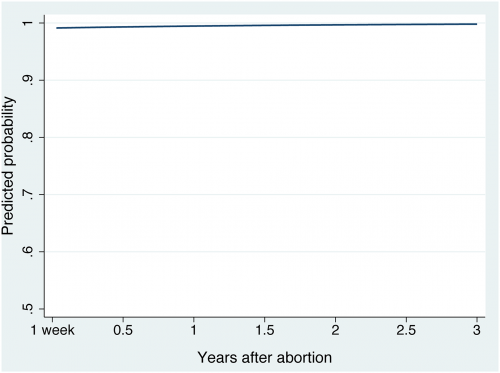

This is your image of the week:

Percent of women reporting that abortion was the right decision over three years:

Over 99% of the women said that the abortion was the right decision at every time point. The line that looks like the upper barrier of the graph? That’s the data.

Overall, measures of negative emotions were relatively low — an average score of under 4 on a 16-point scale at one week and declining to about 2 at three years — and were higher for women who had a more difficult time deciding whether to get an abortion or who subsequently had planned pregnancies. Whether the abortion occurred in the first trimester or near the legal limit did not correlate with emotional response.

In contrast, women reported twice as many positive emotions at one week. Over time, positive feelings about the abortion declined along with negative ones, suggesting that the experience became less emotionally charged overall with distance from the procedure.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.