We recently got the news that Apple and Facebook were going to offer women egg freezing as a fringe benefit of employment. The internet exploded with concerns that the practice discouraged women from becoming mothers at a “natural” age, either by offering an alternative or by sending a not-so-subtle message that childbearing would hurt their careers.

I wasn’t so sure.

First of all, it didn’t seem to me that these women were likely to delay their childbearing till, say, after retirement. So what did it matter to these companies if they had kids at 33 or 43? If anything, an employee taken out of commission at 43 would be even a greater loss, since they’d accumulated more expertise and pulled a higher salary during maternity leave.

Second of all, the discussion seemed to assume that every 30-something female employee was in a happy and stable marriage to a man. The possibility that some women were 30-something and single — that freezing their eggs had nothing to do with their jobs and everything to do with a dearth of marriageable men — didn’t seem to enter into the equation. To me, that seemed like quite the oversight.

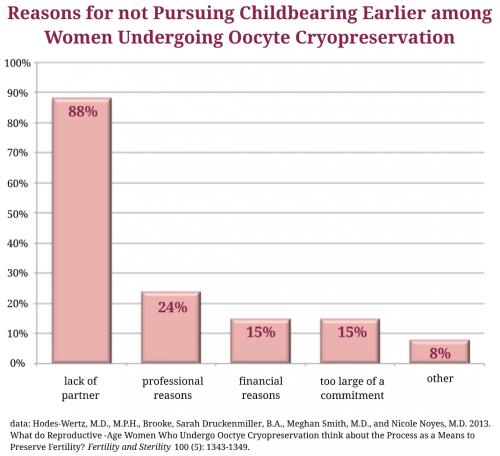

So, I was grateful when sociologists Tristan Bridges and Melody Boyd intervened in this debate. They found actual real data on why women choose “oocyte cryopreservation” and the big answer is not related to their job. As my never-married, 40-year-old self suspected, it was “lack of partner” 88% of the time.

Bridges and Boyd are working on an article re-thinking what it means for women to enter a market full of “unmarriageable men.” In the past, it was mostly working class and poor women who didn’t marry, in part because so few men of their own social status had stable enough employment to contribute to a household. Today women of other class backgrounds are also forgoing marriage, but it isn’t because the men around them don’t make money.

“Men who might be capable of financially providing,” they write, “are not necessarily all women want out of a relationship today.” Women of all classes increasingly want equality, but research shows that many men agree in principle, but fall back on traditional roles in practice.

Freezing one’s eggs is a feminist issue, but not the one that so captivated us a couple weeks ago. It seems to me that Apple and Facebook are simply offering this option as part of a benefits arms race. From that point of view, it’s about class and the widening gap between the rich and everyone else. When women choose this option, though, it’s likely because the gender revolution has stalled. Women have changed; men aren’t keeping up. In the meantime, ladies aren’t settling, even if they’re holding out hope.

Cross-posted at Gender & Society and Pacific Standard.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.