Counting the number of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people is harder than you might think. I’ve written before on just how important it is to consider, for instance, precisely how we ask questions about sexuality. One way scholars have gotten around this is to analytically separate the distinct dimensions of sexuality to consider which dimension they are asking about. For research on sexuality, this is typically done by considering sexual identities as analytically distinct from sexual desires and sexual behaviors. We like to imagine that sexual identities, acts, and desires all neatly match up, but the truth of the matter is… they don’t. At least not for everyone. And while you might think that gender might lend itself to be more easily assessed on surveys, recent research shows that traditional measures of sex and gender erase our ability to see key ways that gender varies in our society.

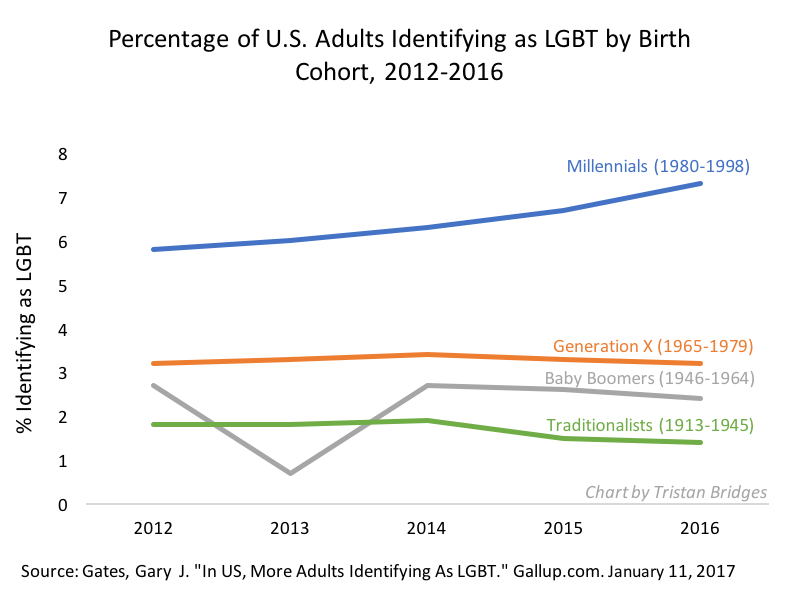

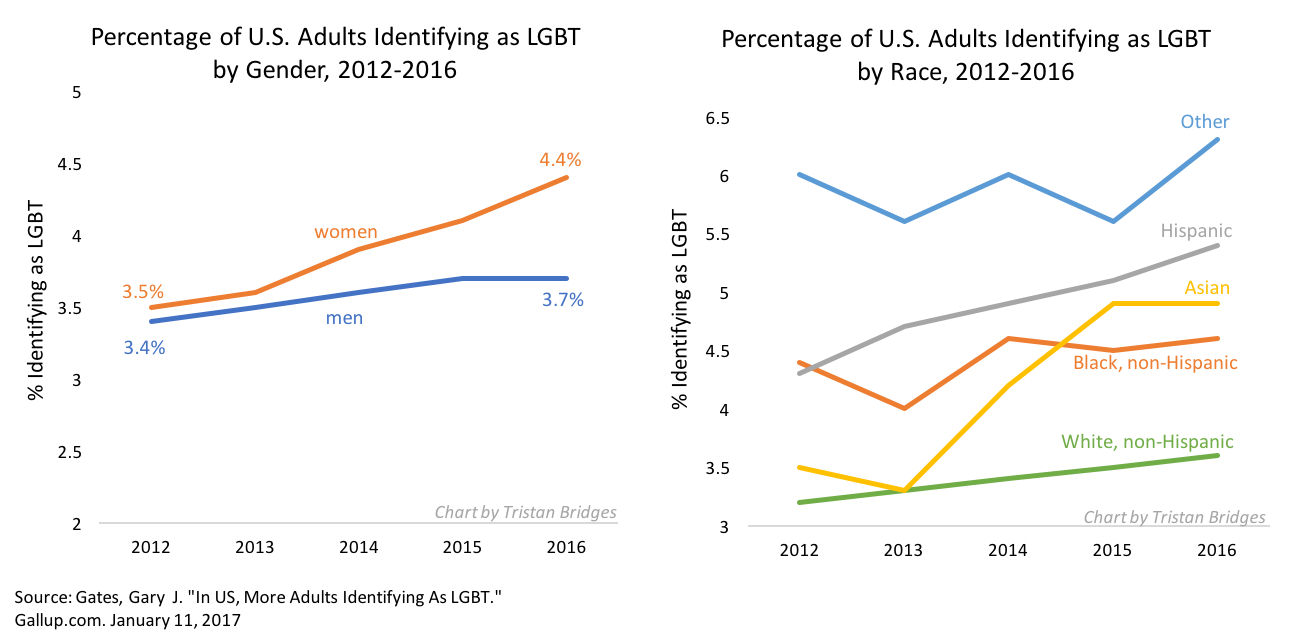

Gallup just released a new publication authored by Gary J. Gates. Gates has written extensively on gender and sexual demography and is responsible for many of the population estimates we have for gender and sexual minorities in the U.S. This recent publication just examines shifts in the past 5 years (between 2012 and 2016). And many of them may appear to be small. But changes like this at the level of a population in a population larger than 300,000,000 people are big shifts, involving huge numbers of actual people. In this post, I’ve graphed a couple of the findings from the report–mostly because I like to chart changes to visually illustrate findings like this to students. [*Small note: be aware of the truncated y axes on the graphs. They’re sometimes used to exaggerate findings. I’m here truncating the y axes to help illustrate each of the shifts discussed below.]

The report focuses only on one specific measure of membership as LGBT–identity. And this is significant as past work has shown that this is, considered alongside other measures, perhaps the most conservative measure we have. Yet, even by that measure, the LGBT population is on the move, increasing in numbers at a rapid pace in a relatively short period of time. As you can see above, between 2012 and 2016, LGBT identifying persons went from 3.5%-4.1% of the U.S. population, which amounts to an estimated shift from 8.3 million people in 2012 to more than 10 million in 2016.

The report also shows that a great deal of that increase can be accounted for by one particular birth cohort–Millennials. Perhaps not surprisingly, generations have become progressively more likely to identify as LGBT. But the gap between Millenials and the rest is big and appears to be growing. But the shifts are not only about cohort effects. The report also shows that this demographic shift is gendered, racialized, and has more than a little to do with religion as well.

The gender gap between proportion of the population identifying as LGBT in the U.S. is growing. The proportion of women identifying as LGBT has jumped almost a full percentage point over this period of time. And while more men (and a larger share of men) are identifying as LGBT than were in 2012, the rate of increase appears to be much slower. As Gates notes, “These changes mean that the portion of women among LGBT-identified adults rose slightly from 52% to 55%” (here).

The gap between different racial groups identifying as LGBT has also shifted with non-Hispanic Whites still among the smallest proportion of those identifying. As you can see, the shift has been most pronounced among Asian and Hispanic adults in the U.S. Because White is the largest racial demographic group here, in actual numbers, they still comprise the largest portion of the LGBT community when broken down by race. But, the transitions over these 5 years are a big deal. In 2012, 2 of every 3 LGBT adults in the U.S. identified as non-Hispanic White. By 2016, that proportion dropped to 6 out of every 10. This is big news. LGBT people (as measured by self-identification) are becoming a more racially diverse group.

They are also diverse in terms of class. Considering shifts in the proportion of LGBT identifying individuals by income and education tells an interesting story. As income increases, the proportion of LGBT people decreases. And you can see that finding by education in 2012 as well–those with less education are more likely to be among those identifying as LGBT (roughly). But, by 2016, the distinctions between education groups in terms of identifying as LGBT have largely disappeared. The biggest rise has been among those with a college degree. That’s big news and could mean that, in future years, the income gap here may decrease as well.

There were also findings in the report to do with religion and religiosity among LGBT identifying people in the U.S. But I didn’t find those as interesting. Almost all of the increases in people identifying as LGBT in recent years have been among those who identify as “not religious.” While those with moderate and high levels of religious commitment haven’t seen any changes in the last five years. But, among the non-religious, the proportion identifying as LGBT has jumped almost 2 percentage points (from 5.3% in 2012 to 7.0% in 2016).

All of this is big news because it’s a powerful collection of data that illustrate that the gender and sexual demographics of the U.S. are, quite literally, on the move. We should stand up and pay attention. And, as Gates notes in the report, “These demographic traits are of interest to a wide range of constituencies.” Incredible change in an incredibly short period of time. Let the gender and sexual revolution continue!

Edit (1/17/17): The graph charting shifts by age cohort may exaggerate (or undersell) shifts among Millennials because the data does not exclude Millennials born after 1994. So, some of those included in the later years here wouldn’t have been included in the earlier years because they weren’t yet 18. So, it’s more difficult to tell how much of that shift is actually people changing identity for the age cohort as a whole as opposed to change among the youngest Millennials surveyed.

Tristan Bridges, PhD is a professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He is the co-editor of Exploring Masculinities: Identity, Inequality, Inequality, and Change with C.J. Pascoe and studies gender and sexual identity and inequality. You can follow him on Twitter here. Tristan also blogs regularly at Inequality by (Interior) Design.