Originally posted at OrgTheory.

Let us start with some basic data.

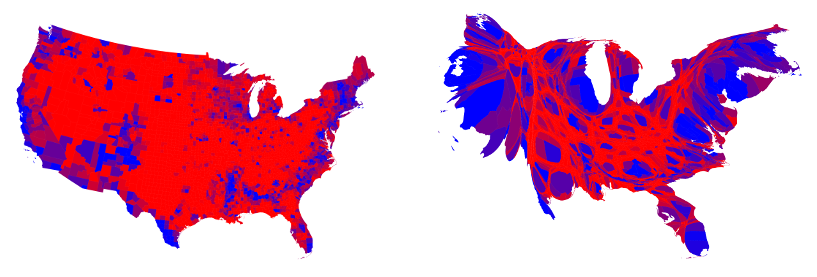

First, the Democratic party has won the plurality or majority of the Presidential vote 6 out of 7 times since 1992. Yet, they won the Electoral College only 4 out of 7 seven times.

Second, the Gallup polls shows that the Democratic party has a modest advantage in identification, with Democratic identifiers and leaners getting about 46% of the population vs. 40% for the Republicans. Yet, the Democrats only control 32% of the governorships (16 out of 50) and they control 29% of the state legislative chambers (29 out of 99). In the national Congress, Democrats do OK. Senate 48% (48 of 52) and House 44% (194 of 435). If we assume that non-party identifiers evenly split, the Democrats are somewhat under-performing, but just a little.

In terms of party control, it is only in Congress where Democrats perform as expected (or maybe slightly under-perform) but in the Presidency and the states, they really do lose more than they should.

Why?

And, please, no, it is not gerrymandering – the Presidency and the governorships are not gerrymandered. Gerrymandering has a modest effect at best. There really is a consistent under-performance.

I’ve been reading a few books that shed light on this really big structural feature of American politics. Each book offers a discussion of an issue in party politics and when you piece them together, you see how the Democratic and Republican parties differ:

In Local Party Organizations, Douglas D. Roscoe and Shannon Jenkins report on a survey of 1,220 party officials at the state and local levels and they ask a number of questions about the operation of local parties.

First, how did state parties help locals? GOP advantage – website development, newspaper buys, campaign expenses, social media; Democratic advantages – computer support, record keeping, staff. Second, GOP local parties were more likely to have “clear strategic goals” and a well managed organizational culture. Third, GOP organizations are more likely to have a complete set of officers, by laws, and headquarters, whiles Democrats are more likely to have a phone listing. Also, Democrats also tend to focus on labor intensive actions, like door-to-door and voter registration. Fourth, these activities often (but not always) correlate with electoral success.

Bottom line: GOP organizations appear to be a little more focused, organized, and strategic. Democrats seem to concentrate a bit more on things people can do (door to door, for example and record keeping).

In Asymmetric Politics, Matt Grossman and David Hopkins delve deep into the culture of the GOP and Democratic parties to argue that they are very different beasts. The GOP is ideologically driven and policy oriented, while Democrats are more oriented toward group solidarity and coalition maintenance. The book is massive and presents lots of data, such as public opinion data, voting patterns, and publications by interest groups and think tanks. Even though I disagree with some points, it is well taken. Democrats have a diffuse ideology and work on the coalition, while the GOP is more “mission oriented.”

David Ricci’s Politics without Stories is a study of political rhetoric and it has a simple message. Look at the philosophers, wonks and orators of the Democratic party and you see nuance and sophistication. Look the the GOP and you see more direct narratives. To quote the great Kieran Healy, Republicans “fuck nuance.“

What do we learn from this overview?

From top to bottom, the Democratic and Republican parties show important and consistent differences. Not just ideological differences, but qualitative differences in how their parties are organized and how they behave. Democrats, to simplify, are “people oriented” and focus on social practices and ideology that fits that general perspective. In contrast, Republicans are a little more task oriented, which translates into more focused and digestible rhetoric and more of an institutional interest in concrete results. There is probably more to this story, but this is a good start.

Fabio Rojas, PhD is Professor of Sociology at Indiana University. He is the author of From Black Power to Black Studies and Theory for the Working Sociologist, and co-author of Party in the Street: The Antiwar Movement and the Democratic Party after 9/11. He has also written an advice book for graduate students and tenure track professors called Grad Skool Rulz.