The Washington Post recently covered a leaked email exchange from the University of Maryland in which the school’s Mock Trial team assistant coach lamented the “mediocre” to “poor” performance of Latinx students and asked if any of them had to be included to satisfy diversity requirements for the makeup of the team. While an embarrassing situation for both the students and the authors of the e-mail exchange, this event reflects recent research in law and society that addresses questions of race, gender, immigrant background, and inequality in the legal profession and among law school students.

While law firms put a high value on American law school training, not everyone gets the same benefits from a legal education. Students of color who are the children of immigrants earn less after graduating from law school. Implicit biases can also determine who gets hired at elite jobs and exert pressure on these students while they are in school. This recent incident at Maryland shows how these patterns affect minority students’ everyday experiences in law school.

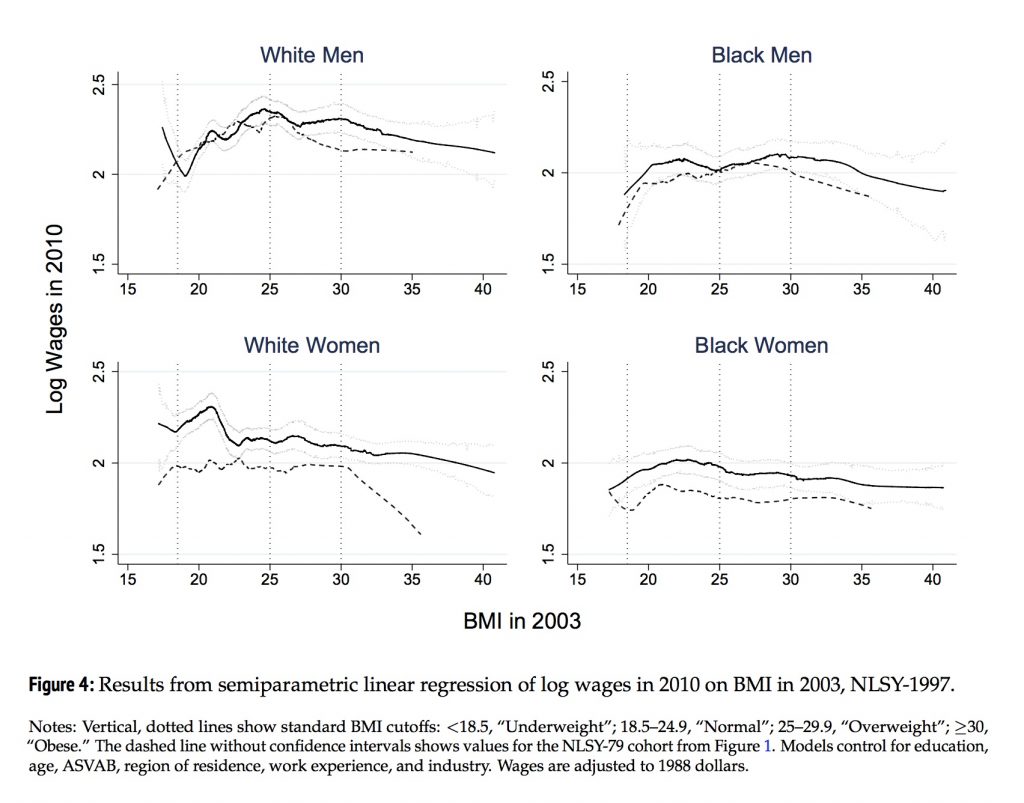

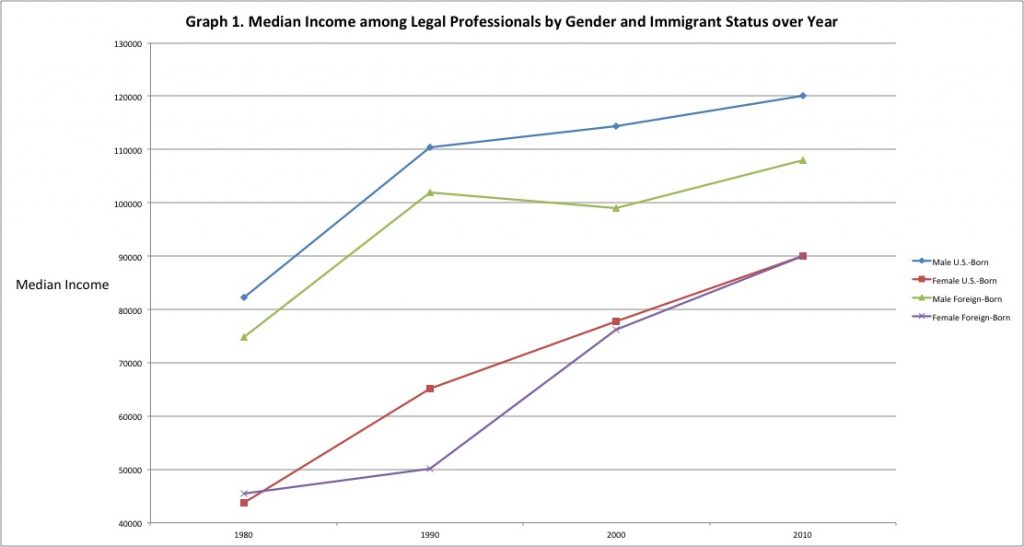

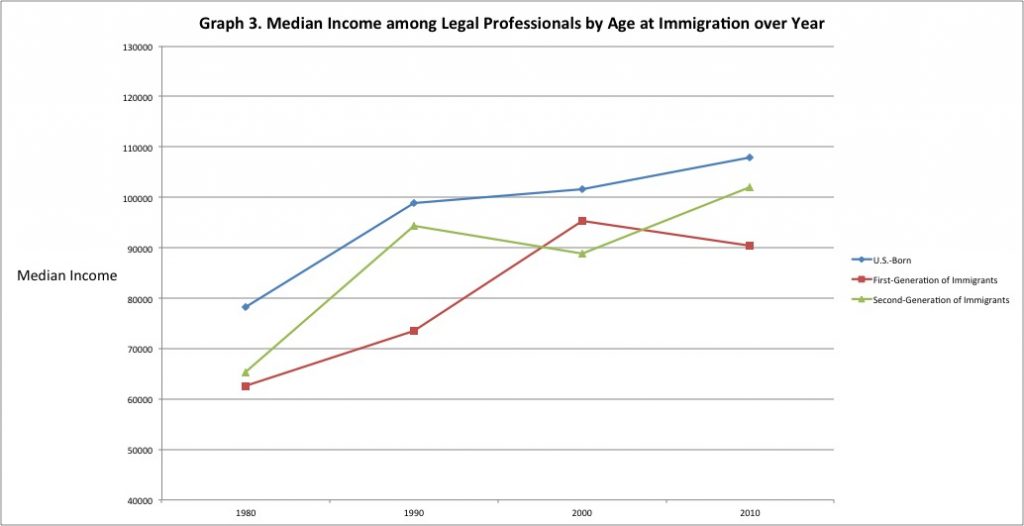

Our analysis emphasizes the persistent inequality in the median income level among lawyers in the United States. There are sizable differences in earnings across race and gender. We have found that, while immigrant status alone is not always negatively associated with income, it does compound the income disadvantage of immigrants when combined with race and gender.

Prepared by the authors. Source: U.S. Census and American Community Survey 1970-2010. All values are in 2010 U.S. dollars. These charts refer to individuals who were in the labor force, employed in the legal profession, and worked in the legal services industry.

One issue that has come up in the course of our study is the question of whether law school matters. We considered that the first generation of immigrants is likely educated abroad, whereas the second generation is potentially educated in the U.S. Although we do not have a direct measure of whether the immigrants in our sample have received their law degree from an American or a foreign law school, previous research has found that age at immigration is a valid proxy measure for place of education.

We do find a slight income advantage for those educated in the United States. However, as the incident in Maryland might suggest, education alone may not determine future professional success as a lawyer. Because the law school environment emphasizes network building and socialization through extra-curricular activities, such as moot court or mock trial, students who are not selected for these opportunities (especially on the basis of race!), may be additionally disadvantaged when looking for a job as well as in the marketplace.

We do find a slight income advantage for those educated in the United States. However, as the incident in Maryland might suggest, education alone may not determine future professional success as a lawyer. Because the law school environment emphasizes network building and socialization through extra-curricular activities, such as moot court or mock trial, students who are not selected for these opportunities (especially on the basis of race!), may be additionally disadvantaged when looking for a job as well as in the marketplace.

Alisha Kirchoff is a PhD student and Associate Instructor of sociology at Indiana University. Her research is in law and society, political sociology and comparative sociology. She is also currently working as a digital content producer for Contexts Magazine.

Vitor Martins Dias is a graduate student in the Department of Sociology at Indiana University-Bloomington. Prior to leaving Brazil to pursue his LL.M. at Indiana University Maurer School of Law, he received his LL.B. and LL.M., respectively, from Centro Universitário do Pará and São Paulo Law School of Fundação Getúlio Vargas. He is broadly interested in the areas of development, the legal profession, law and society, political economy, political sociology, and inequality.