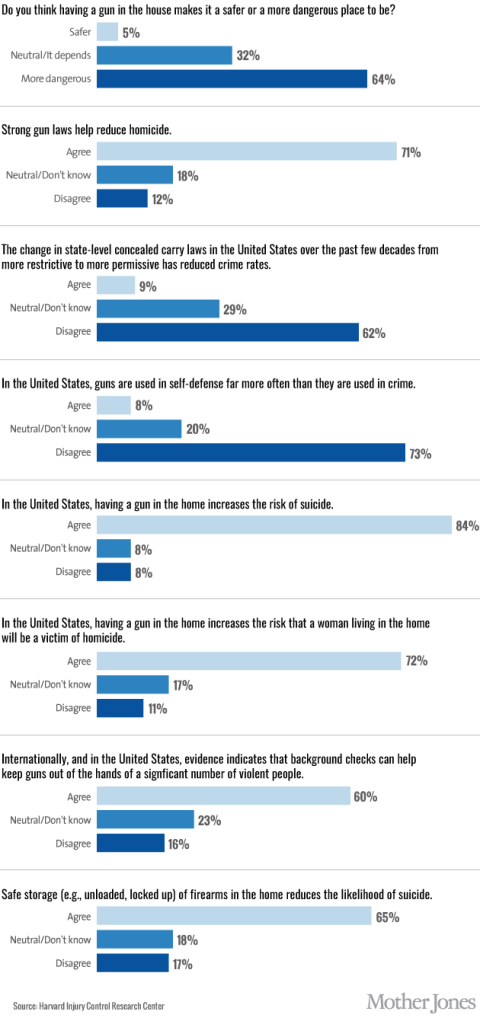

In the face of contentious debate about the value of guns, public health professor David Hemenway decided to have the experts weigh in. He modeled his research on the study of climate change experts that produced the familiar statistic that 97% of them believe that humans are causing climate change. He identified 300 scholars who have published about firearms in the fields of public health, public policy, sociology, and criminology. About 100 each have replied to nine surveys asking their opinions about common controversial statements.

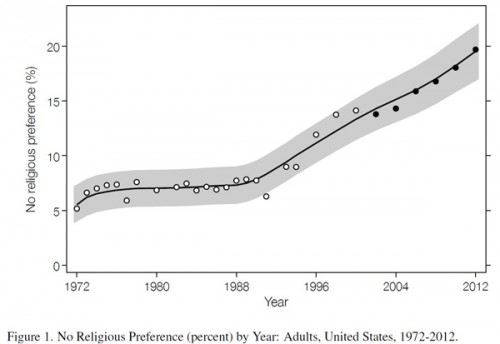

Here is your image of the week:

At Mother Jones, Julia Lurie writes: These data “show that a clear majority of experts do not buy the NRA’s arguments.”

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.