The recent controversy about local news stations in the Sinclair Broadcasting Group reading a coordinated, nationwide message against “fake news” raises questions about the state of news consumption in the United States. Where are Americans getting their news from? If more people are reading the news online, did the Sinclair message have a large impact?

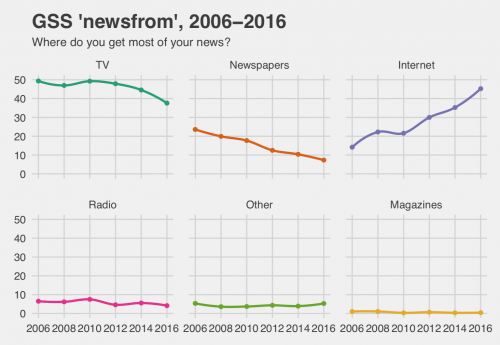

The General Social Survey asks respondents where they get most of their information about the news. This graph shows big changes in Americans’ primary news source, including the rise of online news and the decline of television and newspapers. Notably, in the 2016 GSS, the Internet overtook TV as Americans’ primary source of news for the first time.

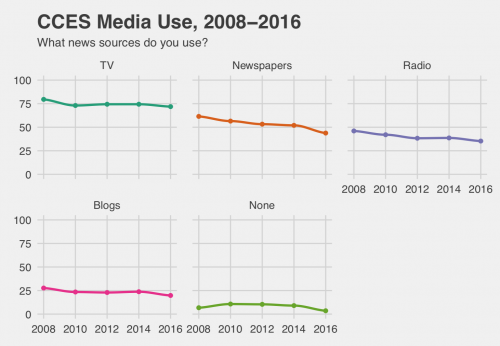

Another survey, The Cooperative Congressional Election Survey, takes a different approach. They ask respondents to select whether they use newspapers, blogs, television, or other sources for their news information. When a survey doesn’t ask respondents to pick a primary source, we see that use rates are more steady over time as people still use a variety of sources.

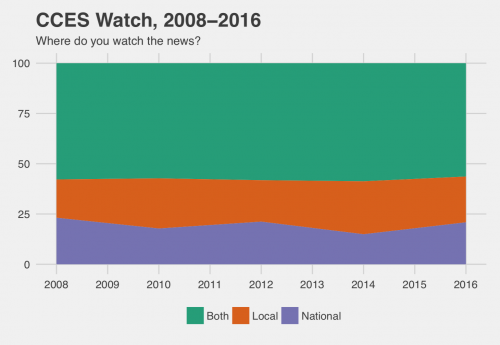

Reported rates of news watching have also stayed pretty stable over the last eight years, with about three-quarters of Americans getting some of their news from TV. Of people who watch news on TV, many respondents report that they watch both local and national news, and this choice has stayed relatively stable over time. Since local news is still a steady part of our news diet, the Sinclair broadcast had a much broader potential reach than we would typically assume about news today.

Ryan Larson is a graduate student from the Department of Sociology, University of Minnesota – Twin Cities. He studies crime, punishment, and quantitative methodology. He is a member of the Graduate Editorial Board of The Society Pages, and his work has appeared in Poetics, Contexts, and Sociological Perspectives.

Evan Stewart is a Ph.D. candidate in sociology at the University of Minnesota. You can follow him on Twitter.

Andrew M. Lindner is an Associate Professor at Skidmore College. His research interests include media sociology, political sociology, and sociology of sport.

Inspired by demographic facts you should know cold, “What’s Trending?” is a post series at Sociological Images featuring quick looks at what’s up, what’s down, and what sociologists have to say about it.