The 2018 General Social Survey data was just recently publicly released. We were eager to see how things shifted, especially for the demographic questions on sexual identity. As of 2018, it has officially been one decade that GSS has been asking respondents to characterize their sexual identity on the survey, you can self-classify as “heterosexual or straight,” “gay,” “lesbian,” “homosexual,” “bisexual,” or “don’t know.” This is only one way to measure sexual identity among many, but the growth in LGB identity has been generally comparable across instruments in the past.

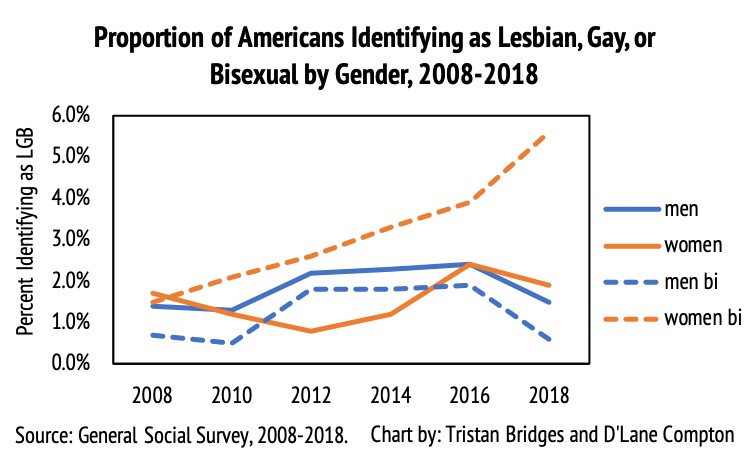

As Tristan has noted before, reporting on shifts in the LGBT population treats the group as homogenous and artificially presents growth in LGBT identity as though it might be equally distributed among the L’s, G’s, B’s, and T’s. But that’s not true. Bisexual women account for the lion’s share on the growth in LGBT identification. And, as Tristan and Mignon Moore showed in 2016, young Black women account for a disproportionate amount of the growth in LGB identification.

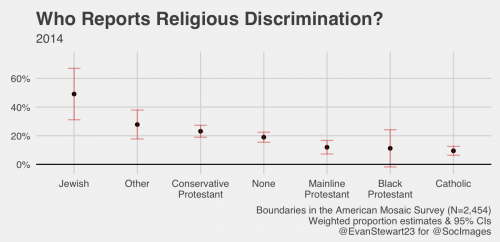

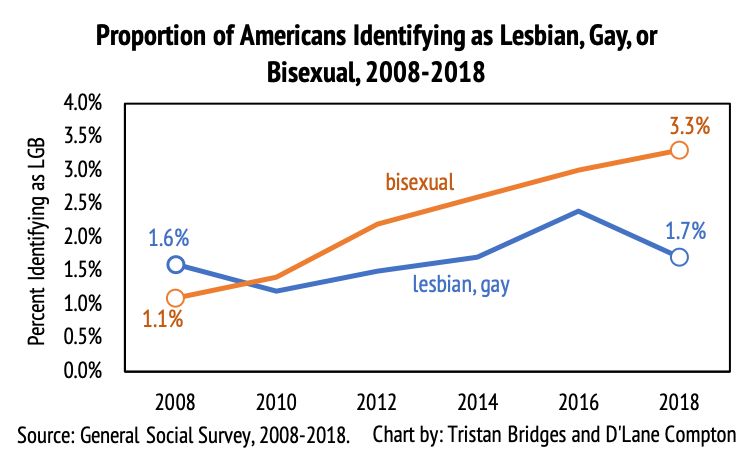

Data from GSS shows an increase in LGB identification between 2008 and 2018. Below, we charted shifts in those identifying as lesbian and gay alongside those identifying as bisexual. Consistent with what Tristan showed in 2016, bisexual identification continues to be increasing at a steeper rate.

In fact, when you look at the proportions identifying as lesbian and gay or bisexual in 2008 and compare those with the proportions identifying as lesbian and gay or bisexual in 2018, lesbian and gay identifications have not really moved much. But bisexual identities continue to increase every year.

This is consistent with other national survey work. For example, using the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG), Compton, Farris and Chang (2015) found that almost nine percent of women in the sample and about four percent of men in the sample in 2008 and 2002 reported behavior as bisexual; that is, having sex with at least one male and at least one female partner in their lifetime. Rates of self-identification as bisexual were much lower (in 2008 0.43% of women and 0.38% of men). Perhaps with increases in social tolerance people are more likely to claim bisexual identities today, regardless of their participation in the behavior.

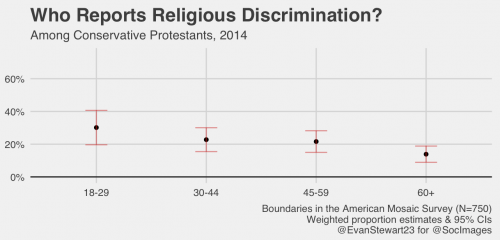

Previous work has also suggested that much of the growth in LGB identities is happening among women. The GSS data show that the shift appears to be primarily happening among bisexual women. Indeed, bisexuality continues to be a more popular sexual identity than lesbian among women, but a less popular sexual identity than gay among men, as others have shown. As of 2018, almost 6% of women responding to the survey identified as bisexual compared with 1.5% in 2008. Comparatively, shifts in lesbian identities among women and both gay and bisexual identities among men really haven’t shifted much.

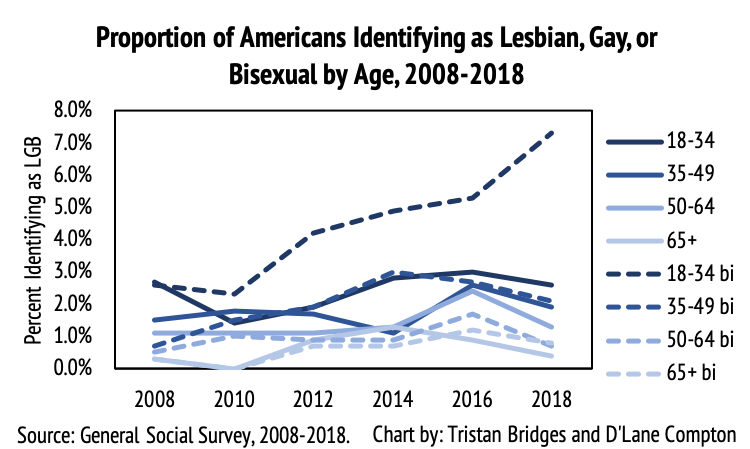

And similar to previous analyses (here, here, and here), this shift is particularly pronounced among the young. The figure below shows changes in lesbian and gay identities alongside shifts in bisexual identities for four separate age cohorts. The real shift in among bisexual identification among 18-34 year-olds. Between 7 and 8% identified as bisexual on the 2018 GSS survey. This is all the more interesting when you look at the 2008 data on these figures. Bisexuality did not stand out in these data in 2008. In fact, in 2008, more people identified as lesbian and gay than bisexual. This shift has emerged and grown in an incredibly short period of time.

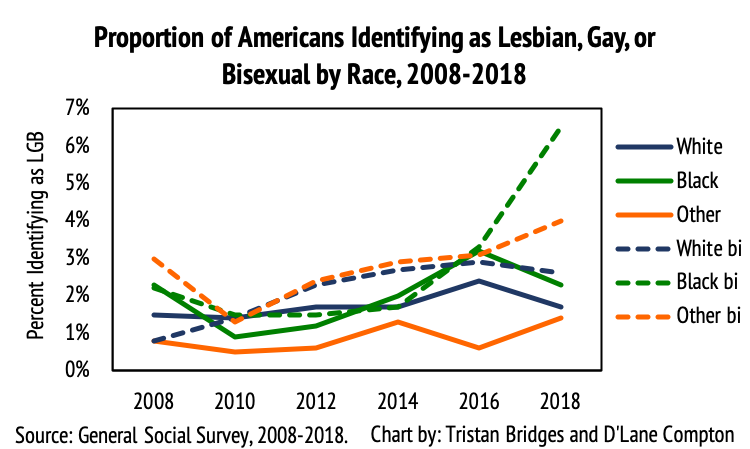

As other data have shown as well (see here and here, for instance), people of color account for a disproportionate amount of this shift. Black bisexuals accounted for almost 7% of Black respondents on the 2018 GSS. That’s a big shift as well. And while bisexual and lesbian/gay identities were moving along similar trajectories for Black Americans through 2016, as of 2018, bisexuality was much more common (as has been true for White respondents and those of other races… yes “other race” is actually the category GSS uses… and no, it’s not a good idea).

So what do we do with all of this? One thing that we ought to take from this is to take scholarship on bisexuality more seriously. As a sexual identity, bisexuality is less studied than it ought to be. But bisexuality has continued to grow and continues to represent a larger number of people’s sexual identities than lesbian and gay combined. This is interesting for a number of reasons, but one is that much of the growth in the LGBT community might actually be the result of changes in the population of bisexual identifying people (and this is a group that is disproportionately composed of women). Whether bisexual identifying people understand themselves as a part of a distinct sexual minority, though, is a question that deserves more scholarship. If we are going to continue to group bisexuals with lesbian women and gay men when we report on shifts in LGB populations, this might be something that deserves better understanding and more attention. Context matters in how we understand identities and how they change or evolve over time.

Originally posted at Inequality by Interior Design. Read more and dive into the details there!

D’Lane R. Compton, PhD is an associate professor of sociology at the University of New Orleans with a background in social psychology, methodology, and a little bit of demography, they are usually thinking about food, country roads, stigma, queer nooks and places, sneakers and hipster subcultures. You can follow them on twitter.

Tristan Bridges, PhD is a professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He is the co-editor of Exploring Masculinities: Identity, Inequality, Inequality, and Change with C.J. Pascoe and studies gender and sexual identity and inequality. You can follow him on Twitter here. Tristan also blogs regularly at Inequality by (Interior) Design.