Is technology – especially communications technology – a necessary component of contemporary fiction? This is the question posed by Allison Gibson in an excellent piece posted earlier this week; it shouldn’t really surprise most people that she comes down on the side of “yes”, but the question – and its implications – are worth some more serious consideration. Especially when one considers setting, or (I don’t love the term but it has a certain utility) “genre”.

The ubiquity of communications technology and social media would seem to make its inclusion in contemporary fiction a no-brainer, writes Gibson, but with ubiquity comes an element of the mundane. There are all kinds of tasks that people perform as a matter of course in everyday life that nevertheless aren’t included in your average narrative, partly for reasons of brevity, but also – and this is the crucial point – because they don’t do anything to progress the story, and when you’re writing fiction, pretty much anything that doesn’t do that singular job in some capacity probably shouldn’t be there. The thing about communications technology is that it’s about communication – like the fortuitous arrival of a letter or a mysterious telephone call, an email or text message between characters serves a specific narrative function, whether that function is to reveal important information about the characters themselves or to introduce something that will move the plot along. “Think of it this way,” writes Gibson, “in most cases, a bowel movement will not move the plot forward; an email will.”

Additionally, as many writers have observed, convincing storytelling is fundamentally about telling the truth – not in the sense of relaying a factual account of a series of events but in constructing a world and populating it with characters that behave in ways that your reader will find convincing. Good storytelling is breathing reality into the unreal; a false note breaks the spell, because it fills an attentive reader with the inescapable feeling that what they are reading is, on some level, unbelievable. A contemporary story without any reference to technology is probably going to feel that way. A character shouldn’t be ignorant of crucial information that could be easily obtained through a Google search unless there’s a good reason for her to have neglected to Google it. Two characters separated and trying to work out logistics should be able to communicate via cell phone unless one of them has lost theirs or forgotten to charge it. These are tiny mundanities, but their absence would be conspicuous.

Their absence – or their misuse. I think we can all call to mind instances in movies and TV shows where the internet makes an appearance in such a way that you wonder if the scriptwriter has actually ever used the internet at all, or just means to eventually check out that information superhighway that all the kids are talking about.

Writing technology into contemporary fiction, Gibson notes, introduces its own set of unique issues: how central to make the tech? How much do you refer to it? What is it actually there to do, if it’s more than to add depth or realism to worldbuilding? And what do you do when the tech you’re writing about is out of date by the time the book comes out (I think a lot of people outside of the publishing industry may not know how long it takes to get a book published. It can take years. And that’s after you sign contracts.)?

One example of a book series that is laughably, insanely bad at this is the Evangelical apocalyptic Left Behind by Tim LaHaye and Jerry Jenkins (which is being wonderfully and ongoingly deconstructed over at The Slacktivist). The series was started before the age of cell phones but continued throughout their spread, and is supposedly set in the near future – and there is nary a cell phone to be found in most of its scenes, despite the fact that characters spend mind-numbing amounts of time on the phone addressing relatively bland things in very bland ways. LaHaye and Jenkins actually present a great example of how overreliance on technology to move the plot along creates major storytelling problems; a few crucial phone calls help bridge gaps between scenes and events and tie things together as well as move them forward, but scene after scene of endless phone conversations quickly becomes tedious in the extreme. And the fact that the technology is badly dated only calls attention to this.

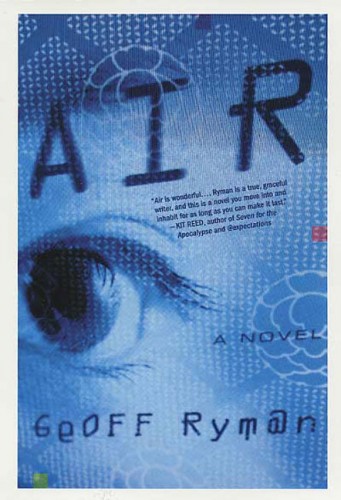

If nothing else, the technology problems in Left Behind illuminate a slightly different problem than your technology going out of date by the time of release: how exactly do you play techno-futurist when writing in the near future? Or the far future? Every science fiction writer pretty much ever has had to either grapple with this problem or choose to ignore it (guess which tends to produce better SF) but SF writers are usually inherently dealing with technology in a different way than their contemporary fiction brethren. When we write SF, often we’re explicitly writing about technology, or at least about the effects that technology has on people and their lives. One is therefore extrapolating forward based on very incomplete data, and often one gets things wrong – many people in the early 20th century predicted that we’d have flying cars and moon bases by now but almost no one conceived of anything like the internet. Some writers have gotten things very close to right, in terms of feelings and concepts if not in the details of the technology itself – William Gibson and Geoff Ryman are two names that spring immediately to my mind.

Science fiction writer Larry Niven has laid out some guidelines for what writers should pay attention to if they want to make informed guesses about future tech – and ultimately these guidelines have far more to do with the enduring qualities of people than with technology itself:

- Look for the goals humankind will never give up. Instant travel, instant education, longevity. Then try to guess when it will appear and what it will look like.

- Pay close attention to parasite control. There is always someone who wants the money for something else.

- You’re obliged to predict not just the automobile but the traffic jam and the stranglehold on gas prices.

- Nobody invents anything unless there is at least the illusion of a profit.

So even if SF writers are free to invent and speculate and not be held especially accountable for guessing wrong, one can still make guesses that feel more true than not. We live in a world where documentation and communication are both massively prevalent and that’s reflected in our technology; present me a future world where that isn’t true and I’ll need you to give me some good reasons why not. Likewise, general trends seem to be moving in the direction of technology becoming ever-smaller and more portable; mobility appears to be a crucial element for most things. Anyone writing about the near or even the far future of human society is going to have to address that on some level. Increasingly the devices we use are linked and the information we store on them is accessible from a number of points; this all means something in terms of how we move through and interact with each other and the world. It’s small, in many cases it’s mundane, but it’s these things that create a world that feels real to us. Neglect it at your peril.

I ran into this myself when working on the worldbuilding for my forthcoming book Line and Orbit, which is set in the distant future and works with – really, relies on – a number of common space opera tropes. As such, my coauthor and I weren’t hugely concerned with exacting scientific accuracy or highly realistic speculations about technology, but in one particular scene, I did have to deal with the idea of cell phones. What the hell would they look like? How would they work? How would they resemble what we have now, and how might they be different? In the end I went with an implant in the brain itself, but it felt incomplete and possibly not as richly imagined as it might have.

Also, what happens to the internet once humanity is spread across multiple worlds? That’s a question I never really dealt with at all, but I think it’s an interesting one.

Regardless, as I indicated earlier, this is where I feel that SF particularly shines, and why I think that it still allows us to tell powerful, important stories: more than contemporary fiction, it allows us to perform thought experiments with technology and society – and with technology and individuals. It’s really more than guessing; at its best it’s highly theory-driven imagining. What if a version of the internet that exists inside people’s brains came to a remote village in Asia? (Geoff Ryman – Air) What if interfacing with computer networks was a profoundly physical experience? (William Gibson – The Sprawl Trilogy) What does an AI growing inside a human mind think and feel? (Catherynne M. Valente – Silently and Very Fast) What happens to digital news media if current trends continue unchanged? (Paolo Bacigalupi – “The Gambler”)

And then there’s steampunk, which – at its best – attempts to reimagine past technologies with expanded forms and functions.

Ultimately human storytelling of any kind is going to have to grapple with human experience. Technology is a necessary part of that experience, in the past, present, and almost certainly in the future. Storytellers of any stripe shouldn’t shy away from that. When done well, the products are remarkable and true, and one can’t ask for much more from one’s stories.

Sarah Wanenchak writes and lives SFnally under another name that shouldn’t be too hard to track down if you try. Incidentally, Line and Orbit will be released by Samhain Publishing in late 2012/early 2013.

There has been much debate surrounding the role of social media in the 2011 Egyptian Revolution. Though the movement that led to the ousting of President Hosni Mubarak has been dubbed the “Facebook Revolution,” it is not the first time that foreign media has been quick to connect a social networking site with a popular uprising. The 2009 Iranian protests were labeled the “Twitter Revolution,” and ever since there are those who are adamant that social media is a vital instrument for mobilizing the masses while others argue that social media is just a new means of communication in a history of popular uprisings that fared quite well without these new technological innovations. This paper explores the impact of social media on the development of Egyptian civil society and mobilization by the opposition. It shows that while social media is not necessary for organizing revolutions, it served two important functions leading up to the Egyptian Revolution. It aided in building a politically conscious civil society over the course of a number of years prior to the Revolution and it lowered the threshold for engaging in political participation and dissent by providing a relatively safe, easily accessible space for political debate in a country that outlawed gatherings of five or more people.

There has been much debate surrounding the role of social media in the 2011 Egyptian Revolution. Though the movement that led to the ousting of President Hosni Mubarak has been dubbed the “Facebook Revolution,” it is not the first time that foreign media has been quick to connect a social networking site with a popular uprising. The 2009 Iranian protests were labeled the “Twitter Revolution,” and ever since there are those who are adamant that social media is a vital instrument for mobilizing the masses while others argue that social media is just a new means of communication in a history of popular uprisings that fared quite well without these new technological innovations. This paper explores the impact of social media on the development of Egyptian civil society and mobilization by the opposition. It shows that while social media is not necessary for organizing revolutions, it served two important functions leading up to the Egyptian Revolution. It aided in building a politically conscious civil society over the course of a number of years prior to the Revolution and it lowered the threshold for engaging in political participation and dissent by providing a relatively safe, easily accessible space for political debate in a country that outlawed gatherings of five or more people. The compression of space and time brought about by globalization, and the consequent intensification of interactions beyond traditional barriers has given rise to global issues which require global solutions. Chief among these are moral issues, which are back at the center of academic debates on the inherited vernacularity or universality of moral values. By deploying and extending the usage of Chomsky’s Universal Grammar to the realm of morality, this paper will draw on empirical data gathered in Iran to argue that human beings are born with a universal moral faculty which underlies human actions and omissions. Virtual space, thanks to its decentralized, rhizomatic and discursive nature – as opposed to the arborescent structures of the state apparatus – is the platform upon which this potentiality can operate. Webs of non-formal learning and networking provide single individuals/communities, from antipodes of the world, the means of communication necessary for initiating an open dialogue beyond institutionalized stereotypes which have traditionally fueled the machines of states’ biased politics. Based on the data collected from an online survey in Iran, the paper concludes that although Iranians, for many reasons, are being detached from and deprived of free movement and interactions, they nevertheless manage to bypass existing barriers and contribute significantly to the actualization of an emerging global moral brain – a process which testifies to the existence of a universal moral grammar.

The compression of space and time brought about by globalization, and the consequent intensification of interactions beyond traditional barriers has given rise to global issues which require global solutions. Chief among these are moral issues, which are back at the center of academic debates on the inherited vernacularity or universality of moral values. By deploying and extending the usage of Chomsky’s Universal Grammar to the realm of morality, this paper will draw on empirical data gathered in Iran to argue that human beings are born with a universal moral faculty which underlies human actions and omissions. Virtual space, thanks to its decentralized, rhizomatic and discursive nature – as opposed to the arborescent structures of the state apparatus – is the platform upon which this potentiality can operate. Webs of non-formal learning and networking provide single individuals/communities, from antipodes of the world, the means of communication necessary for initiating an open dialogue beyond institutionalized stereotypes which have traditionally fueled the machines of states’ biased politics. Based on the data collected from an online survey in Iran, the paper concludes that although Iranians, for many reasons, are being detached from and deprived of free movement and interactions, they nevertheless manage to bypass existing barriers and contribute significantly to the actualization of an emerging global moral brain – a process which testifies to the existence of a universal moral grammar. The historical events of recent years have originated many studies about the role of technology as a catalyst for civic organization and social mobilization. Some authors argue that technology enhances the construction of new forms of deliberative and participatory democracy. It is less common to find theoretical and empirical work about the subjects that take part in these movements. This paper argues that in the case of Mexico, with a significant digital, cultural and economic divide, instead of ‘smart mobs’ (Rheingold 2002) we are witnessing the emergence of a new digital elite. This cyberintelligentsia –composed of educated urban geeks- acts as a main instigator (Kanter 2010) of social cyberprotest. This paper reformulates Putnam’s (1976) approach to political elites and the different capitals (in the sense of Bourdieu 1983) to explain the emergence of digital elites as key actors in Mexican cybermovements and their role in public policy making. The paper concludes that although technology has opened the possibility for a group of citizens to influence decision-making, this does not entail a quantitative increase of citizen participation in public affairs.

The historical events of recent years have originated many studies about the role of technology as a catalyst for civic organization and social mobilization. Some authors argue that technology enhances the construction of new forms of deliberative and participatory democracy. It is less common to find theoretical and empirical work about the subjects that take part in these movements. This paper argues that in the case of Mexico, with a significant digital, cultural and economic divide, instead of ‘smart mobs’ (Rheingold 2002) we are witnessing the emergence of a new digital elite. This cyberintelligentsia –composed of educated urban geeks- acts as a main instigator (Kanter 2010) of social cyberprotest. This paper reformulates Putnam’s (1976) approach to political elites and the different capitals (in the sense of Bourdieu 1983) to explain the emergence of digital elites as key actors in Mexican cybermovements and their role in public policy making. The paper concludes that although technology has opened the possibility for a group of citizens to influence decision-making, this does not entail a quantitative increase of citizen participation in public affairs. In Deleuze’s society of control, inevitably permeated by cybernetic machines and computers – two exponents of digital culture –, digital communication acts increasingly, on one hand, as one of the main ways we have to keep in touch, create and access knowledge, produce cultural and informational goods; one the other hand, it acts as a way to exercise permanent control through the protocols. This paper discuss how, in this scenario, in which control protocols and cultural softwares are essential intermediaries in our communication, hacker activism (or hacktivism) becomes relevant, so that the hackers, because of their specific skills, become political actors that cannot be relegated. More specifically, we bring some results concerning the “hacktions” of Anonymous group in Brazil. Thus, we discuss the literature related do hacker culture and hacktivism in order to indentify the motivations and ideals of these actors, here perceived as a symbol of a new movement of resistance that, given the current circumstances, occurs not out of them, but through protocols.

In Deleuze’s society of control, inevitably permeated by cybernetic machines and computers – two exponents of digital culture –, digital communication acts increasingly, on one hand, as one of the main ways we have to keep in touch, create and access knowledge, produce cultural and informational goods; one the other hand, it acts as a way to exercise permanent control through the protocols. This paper discuss how, in this scenario, in which control protocols and cultural softwares are essential intermediaries in our communication, hacker activism (or hacktivism) becomes relevant, so that the hackers, because of their specific skills, become political actors that cannot be relegated. More specifically, we bring some results concerning the “hacktions” of Anonymous group in Brazil. Thus, we discuss the literature related do hacker culture and hacktivism in order to indentify the motivations and ideals of these actors, here perceived as a symbol of a new movement of resistance that, given the current circumstances, occurs not out of them, but through protocols.