In the previous installment of this series, I set up what I characterize as the two primary areas of argument that stand against my primary claim: that social media technology and other forms of ICT, far from constraining emotional connections and the emotional power of solidarity-creating rituals, actually serve to facilitate emotions and the powerful connective work that emotional interaction does.

There are a number of ways that one could argue this is done, and Jenny Davis makes an especially pertinent argument in her post about the social cost of abstaining from digitally augmented forms of interaction. For the purposes of this piece, I want to focus my attention on the capacity of ICTs to facilitate the generation of emotional energy around contentious political action – especially contentious political action in a context of violent repression.

Recall that in my previous post, I split the arguments on which I focused into two camps: the idea that emotional energy in social interaction – particularly in solidarity rituals – requires bodily co-presence in order to be effective, and the idea that technology – both in terms of documentation of violence and in terms of violent action itself – creates emotional distance from events and, in effect, prevents any significant emotional connection to them. In this post, I’ll argue against those points. Let’s get to it.

Augmented Co-Presence

One must allow that many of the things that work to create emotional energy (EE) and emotional connections to events and to one’s fellow participants in an event do not translate particularly well over digital media – the roar of a crowd, the smell of a large gathering of people in a particular place and at a particular time, the feeling of a crush of bodies, and the sensation of physical danger should the gathering be met with violent repression. But the lack of these things does not preclude the capacity of ICTs for facilitating the generation of EE.

One of Randall Collins’s qualms, as I characterized it last week, lies in the fact that the generation of EE within an interaction is often about rhythm, about the reciprocal give-and-take that is the distinguishing feature of most social interaction, and which shifts into a massive scale when operating at the level of a crowd that acts and reacts to second-by-second changes in an environment. What Collins is assuming – problematically – is that ICTs do not lend themselves to this kind of immediacy. Perhaps at the time of his writing, they didn’t, but the last few years have seen an explosion of social media that functions quite neatly in real-time; indeed, such is a central part of their appeal. Twitter and livestreaming, two of the primary tools of Occupy in the United States and other movements elsewhere in the world over the last year, work so well precisely because they are so immediate. Watching events update in real-time on one’s Twitter feed has the capacity to both captivate and generate tremendous emotion: I recall evenings spent staring at updates coming in regarding attacks on civilians in Syria and falling into the grip of powerful horror and rage. During the rash of Occupy evictions last fall, following livestreams of the police actions became a powerful form of engagement for those who could not be there in person, a kind of witness-as-participation that one could criticize as slacktivism but which is still undeniably powerful in that it engages the emotions.

This form of engagement serves not only to generate powerful emotion through watching events in real-time, but also to help create discourses around who the players are and what is at stake. For many people, it seems to have been hard to watch footage of police in full, militarized riot gear advancing on unarmed Occupy Oakland protesters and not form some ideas regarding who the “Us” is, who the “Them” are, and what “They” are doing to “Us”. The accuracy of these ideas could and should be debated, but their power should be recognized. As such, this kind of witness-engagement goes beyond the generation of emotion and into attributions of identity, which is a crucial mechanism for mobilization within social movements.

Finally, what an observer sees when they follow a Twitter feed or a livestream is powerful not only because of its immediacy, but because of the ways in which it does not resemble a traditional media narrative. This takes us to:

Unmediated Vulnerability

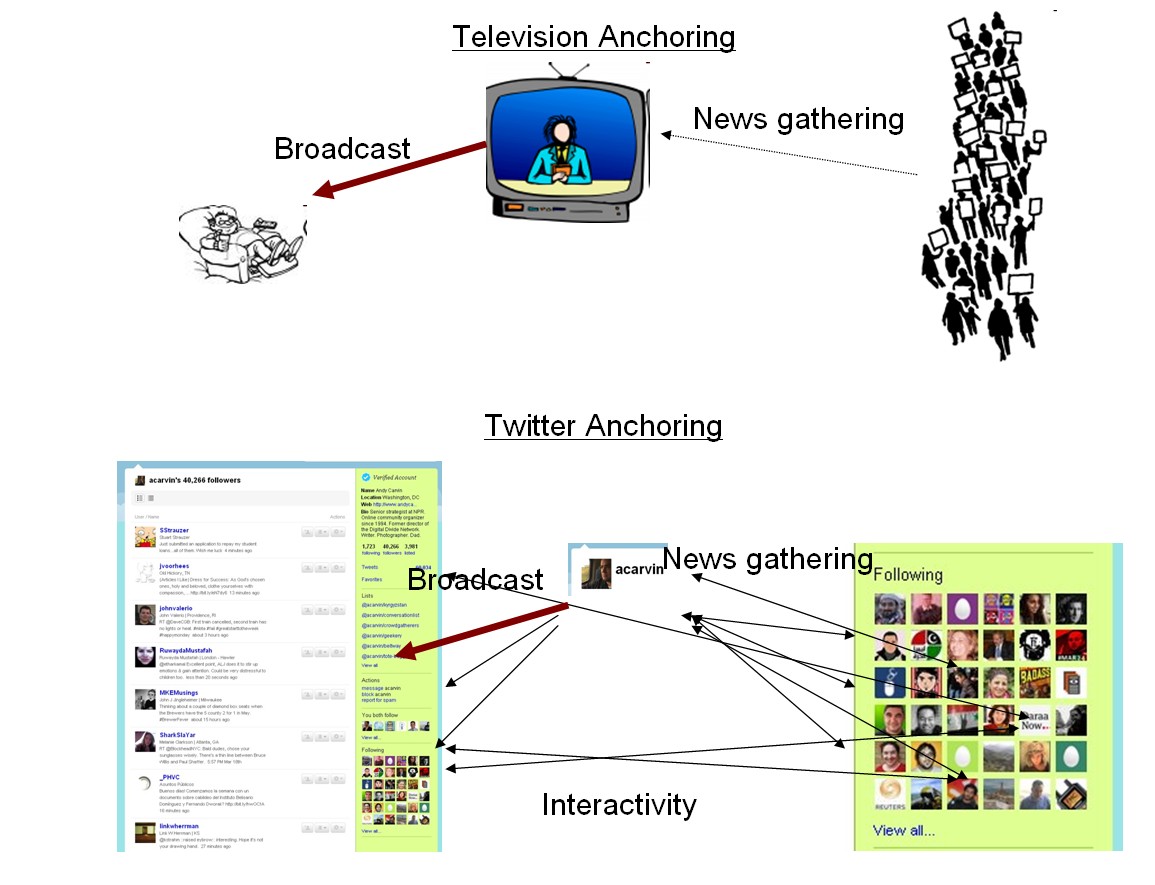

This header is a slight misnomer: it isn’t that tweets or livestreams are unmediated – they are, because all information is mediated by who is sharing it and how it’s being shared. Rather, this kind of streaming information is unpolished, devoid of the slick consumer packaging and careful editing that Baudrillard found so troubling in the First Gulf War. As Zeynep Tufecki notes in her excellent piece on this very phenomenon, the function of the traditional news anchor is almost always not to draw one into an event, but to create distance between the viewer and what is being viewed, through their carefully coiffed demeanor and the ways in which they hurry us from scene to scene in a news cycle.

Events mediated through ICTs destroy that distance by bringing us face to face with the “anchor” and their reactions to what they’re covering. The “anchor” is still mediating the information, but as we follow Tim Pool breathlessly through a crowded New York night or read Andy Carvin’s horrified tweets about videos coming out of Homs, we are invited to feel with and through them as we are immersed in an event together. Witness becomes powerfully participatory because emotion is now an intrinsic part of what we see, and that emotion is part of what we share and see shared. And because we can share the information and add records of our own reactions, the experience of digitally mediated witness becomes more participatory still.

What ICTs facilitate, then, is a form of observation that shades into active engagement, and works to create and spread powerful emotions and emotion-laden narratives around events, especially political and violent events. And the immediate nature of this technology allows this form of engagement to be rhythmic in much the same way that physical co-presence does: it can build to a crescendo of outrage and horror, leaving the engaged observers emotionally energized even at a distance and even after the event is over.

A final point that must be made at this juncture is that physical presence still matters in this case, in two primary ways. First, even in a digitally mediated event, there still must be something to mediate: someone watching a livestream of an Occupy eviction is still watching human bodies engaged in both danger and solidarity. Those bodies have symbolic weight and power, and often they have the most symbolic weight and power of any other part of the movement. A dramatic flush of international outrage was generated around the film of Neda Agha-Soltan bleeding to death in a Tehran street, but it was the physical suffering and death of her physical body that generated that rage. Outrage grew exponentially out of the footage and images of Lt. John Pike pepper-spraying seated UC Davis students, but again, that outrage was generated by and situated around the physical suffering of physical bodies.

Secondly, the power of the kind of EE generated by this form of witness necessarily lies in its capacity to mobilize people into a movement. This might consist of sharing information or providing financial support, but when Occupy encampments sent out eviction alerts through Twitter, what they primarily called for was the presence of physical bodies on the scene. The point is once again to emphasize the augmented nature of this form of contention: the physical and digital do not replace each other but work in tandem and are increasingly inseparable.

In scholarship on violence, social movements, and technology itself, emotion is consistently downplayed, implicit, or not recognized as a factor at all. But the events of the last couple of years should bring home to us that we need to expand our thinking on this point. When we speak of reality as “augmented”, emotions are necessarily part of that, as well as the work that emotions do. What remains to be done is much clearer specification regarding the specific mechanisms and processes involved in this, and what their long-term effects might look like in how we make sense of each other and our own experiences.