Between the emotion

And the response – T.S. EliotMistah Kurtz– he dead. – Joseph Conrad

A version of this essay was delivered at the military sociology miniconference at the annual meeting of the Eastern Sociological Society, 2011.

War is fundamentally a cultural phenomenon. It is profoundly entangled with shared meanings and understandings, stories both old and new, and the evolution of the same. These stories and meanings concern how war is defined, what it means to be at war, how enemies are to be identified and treated, how war itself is waged, and how one can know when war is finished – if it ever is. The shared meanings and narratives through which the culture of war is constructed are diverse: oral stories told and retold, myths and legends, historical accounts, and modern journalistic reports – and it’s important to note how the nature of those last has changed as our understanding of what qualifies as “journalism” has changed as well.

Video games are worth considering in this context, not only because of their pervasiveness but because of their narrative power. They share much in common with film: interaction with them is mediated by a monitor, and they almost always feature a narrative of some kind that drives the action on the screen. However, video games are also different from other forms of media in that they are simulations – they go beyond audio-visual narrative and into at least an attempt to approximate a particular kind of experience. Further, unlike movies and TV, a feature of the experience they offer is active participation. This isn’t to say that movies and TV are passive; they’ve been too often dismissed as such, when viewing those forms of media in fact often involves complex patterns of interpretation and meaning-making. However, the difference is still worth some attention.

I want to argue that this difference has particular implications for how we as a largely civilian population understand war and reproduce the meanings we attach to it. Further, I think that how our games tell stories about war reveals some powerful things about how storytelling in war has changed over time – along with war itself – and how we can understand our own collective psychological reactions to those changes. Finally, I argue that our relationship to war in the context of games highlights some of the ways in which war is digitally augmented – not only on the battlefield and among military population but here among civilians.

Given that we’re talking about games in the larger context of media and warfare, I’ll begin by outlining some of the ways in which media narratives – especially film – have historically contributed to the cultural construction of meanings of war.

As I said above, meaning-making and the construction of understandings of war are traditionally narrative in nature, or at least narratives of various kinds make up a great deal of what there is. Myths and legends are some of the oldest forms of this, and help to construct and maintain cultural ideas regarding what war is like, how it is to be fought and how a warrior should conduct themselves, and what is at stake in war (territory, property, beliefs, etc.). In addition to myths and legends—and sometimes inseparable from them—are historical accounts of war, which relate details about the wars that a nation or a people have been involved in over the course of the past and are therefore pivotal in a people’s understanding of how they arrived at their present condition, who their enemies were and are, who they themselves are in opposition to others, and what they hold valuable and worth fighting for—as well as what they might fight for in the future, and who they might fight for it.

This is an important thing to make an additional note of: images and stories of war tell not only about the wars that have been fought, but about what wars might be fought in the future; they contain information regarding what is both possible and appropriate in terms of war-making. But I want to focus this more narrowly in the recent past, so I rather than the older forms of war narrative, I’ll focus on propaganda, journalism, and film/television.

Wartime propaganda reached a new level of pervasiveness and complexity in the twentieth century, due in large part to emerging media which provided new venues for its spread to the public. Poster were naturally widely used, but film provided the most powerful new medium in which for propagandists to work, and movie theaters were increasingly sites for the proliferation of government sponsored information regarding how wars were being fought, what they were being fought for, and the nature of the enemy. Some of the government sponsorship was direct; some less so—It’s important to note that at this point, the lines between news, entertainment, and overt propaganda were often indistinct at best. World War II was framed as a struggle of good against evil, with the Axis powers presented as fundamentally alien and Other in comparison to virtuous Allies. These narratives were engaged in both constructing and reproducing an understanding of the war as a struggle against a barbaric enemy that could not be reasoned with and which bore no resemblance to the “good” side.

One example of this kind of meaning-making can be found in the Why We Fight film series, commissioned by the US Army shortly after the beginning of World War II and directed by the famed Frank Capra. These films, which were required viewing for American soldiers, presented the Axis as a vicious and barbarous marauding power, entirely bent on subjugating the world. Particularly important in the creation of the films were heavily cut and edited sections of captured Axis propaganda – Capra engaged in the kind of reframing via remixing that we see more commonly today in reference to a wide range of media and cultural sources.

It’s worth noting at this point that dehumanization of the enemy only implies what is at stake but suggests how the enemy is to be treated. An inhuman enemy that is fundamentally evil in the way that the propaganda on both sides depicted can only be eliminated. Killing is constructed as the only possible or reasonable action to take.

War film has a long history, especially in the United States, and different wars are dealt with differently in film, depending on both the war and the era in which the film is made. As the realities of how war is understood change, its depictions undergo a corresponding change in media intended for mass consumption. We can understand this as a response to cultural changes that precede the depictions—but the depictions also help to construct and reproduce the meanings emerging from the changes.

Many of the films depicting World War II were “romantic” in nature, featuring heroic sacrifice in which American determination and courage led to victory. The films both emphasize the conception of the Allied – and specifically American – forces as good people engaged in a righteous cause, and make powerful suggestions about the way in which war can be won. The emphasis on the sacrifice of the body and the meaning of injury is significant: death in war is not only not entirely a negative, but one can have confidence that the sacrifice is undertaken on behalf of ethical leaders and a good cause, and injury and death of a nationalized body take on a justifying function within conflict.

During the Cold War era, we see everything change, specially in the period immediately following the Vietnam War. Many of these films break with the tradition of honorable and necessary sacrifice by presenting Chinese and American soldiers as pawns without agency led by people who don’t value suffering or sacrifice. Films that deal directly with the conflict in Vietnam follow a similar formula, presenting death in war as fundamentally devoid of ideological significance, and criticizing the leaders whose decisions put men in the position to die in battle. Sacrifice is even presented as possessing no deeper significance at all, and the soldiers in war as little more than animals being slaughtered in a conflict of which they have no real understanding. War films made during this period therefore present a trend characterized by deep ambivalence to the meaning of war, to how it is fought and against whom, and to the trustworthiness of the political and military leaders of the nation.

We see this again more recently regarding both the first and the second Gulf Wars, with films depicting of war as surreally pointless. However, some (like 2008’s The Hurt Locker) take a more analytical, documentarian bent. I think the latter especially is a significant development, and can be explained at least in part by the increased prevalence of documentary journalistic accounts in the exposure to current and recent conflicts on the part of the general public. But documentation doesn’t equal a lack of mediation; it’s a form of meaning-making in and of itself, and it makes certain kinds of interpretation possible while precluding others.

The first Gulf War occurred at the dawn of the era of satellite TV and 24-hour news networks. It was arguably the beginning of war-as-spectacle: packaged for mass consumption, more immediate and more real—and yet more removed and more surreal. Despite the amount of news coverage, the image of war with which the American people were presented was bizarrely constructed, with, as Elaine Scarry noted, a marked lack of injured and dead bodies in the discourse around the war. There was no need to present sacrifice as honorable or righteous, since there was no sacrifice. With no concrete depiction of enemy casualties, the enemy remained an undefined, nebulous idea. Jean Baudrillard famously claimed that as a war, it “did not take place” at all, that the media event that was packaged and sold to the American public was a simulation of war that was too bodiless and too asymmetrical to be called a war at all.

Most recently, war film is increasingly technology-focused—and increasingly uncertain and paranoid in its depictions of the experience of war. As in the first Gulf War, the enemy is not clearly defined but is instead heavily abstract, though represented in conflict with Othered individuals: Terror is the enemy, not any specific persons or group of people. Additionally, following the phenomenon of ambient documentation on both an individual and institutional level, the military is shown filming itself, from high-altitude surveillance to video taken by soldiers on the ground and photos captured on cell phones. There is an essential lack of any heroic narrative in most films about the second Gulf War, and though much of the film footage is ostensibly meant to be realistic, it is in turn reflecting an unreal reality that’s simulated in nature, atemporal, and presented in a confusing multiplicity of narrative forms.

Finally, it’s worth noting that with the proliferation of image-altering apps like Instagram, images of war can be used in an attempt to recapture a kind of authenticity that’s both comforting and simplifying (a return to the manichean worldview of WWII) – that “faux-vintage” images of war are a reaction to war that’s becoming increasingly “unknowable” and removed from the perception of many, if not most.

War games themselves are extremely old, with one of the earliest known being chess. In his book Wargame Design, James Dunnigan notes that in terms of its practical design, chess bears a close resemblance to how wars were actually fought at the time, on flat terrain in slow incremental movements with lower class and less powerful front line soldiers defending a king who is less powerful militarily but immensely powerful as a figurehead and symbol.

Dunnigan goes on to explain that most wargames were designed and played by civilians with little military experience, but that by the 19th century, wargame play and design began to shift into the realm of the military itself. An important point to note here is that wargames were not only used by members of the military as a hobby and pastime, but in training and battle-planning. This meant that the games themselves, which had suffered in terms of realism from the limitations in knowledge on the part of their civilian designers, now put a premium on being as realistic a simulation of warfare as possible. They required that their designers and players have a detailed understanding of strategy and tactics, as well as military organization and maneuvers.

Use of wargames on the part of the military began in Prussia and then spread to other European states once it was proven to be an effective technique. It was also made use of in the United States, but its use was generally confined to specific battles. After the end of WWII and as the Cold War began in earnest, this changed, with military wargames taking on a wider scope in both time and space, and a greater consideration of political structure.

At this point it’s important to note the technological context of war itself, and how it was changing during the mid-20th century. It’s a well-known idea within military history and sociology of war circles that WWII introduced a technological component to the fighting of wars that had hitherto been minimal or absent; the idea that wars in general and killing in particular could be refined to a science, calculated and controlled, increasingly mechanized, with a significant degree of physical and emotional distance between killers and killed. Zygmunt Bauman famously tied the existence of the Nazis’ factory-style genocide with major elements of modernity. Joanna Bourke has identified the significance of technological discourse in the ease of killing and the reduction of death in war to numbers and statistics. Emotional pain and guilt on the part of soldiers engaged in bombing missions can literally be measured in terms of altitude from the target, and the aerial bombing of civilian targets became an acceptable method of warfare during both World Wars.

Probably the most important element in the changing landscape of warfare was, as Jeremy Antley points out in his comment on my last post, the existence of nuclear weapons. The line between combatant and noncombatant was already blurry; the spectre of nuclear warfare essentially erased it. Moreover, of all the techniques and weapons of war developed up to that point, nuclear war was the most explicitly scientific in nature, the province of physicists as much as generals.

All of this is to say that as the Cold War kicked into high gear, war and technology – and particularly death and technology – were arguably more inextricably enmeshed than they ever were before. War and technology have always had a close relationship, and the development of new weapons and fighting techniques has always been primary, but now killing was made explicitly calculable – and, by extension, controllable. War was something that could be planned for and explored through gaming and simulation – a set of variables that could be altered to construct a vast range of different scenarios. As wargames shifted from the tabletop to the computer, the variables and scenarios increased in both number and complexity, and simulations could be run at high speeds. The Cold War itself was primarily about strategy, both in the short and long term, about anticipating the movements of the other player in the game.

This reached a significant apex during the first Gulf War, which was extensively planned beforehand with the use of wargaming, specifically a manual game called “Gulf Strike”. The first Gulf War was particular in the history of American warfare, not only in its prominent use of wargames, but in its reliance on and use of digital technology. As a military operation, it was designed to showcase the United States as possessing the technologically dominant military of the future, precise and calculated and efficient, with high results and low casualties. As I mentioned in my previous post, it was this new form of warfare – referred to by the military itself as “full spectrum dominance” – that led Jean Baudrillard to claim that what was presented to the American public was not a war at all but a simulation of the same, bloodless and clean, and also entirely asymmetrical. It was iconic war-as-game, and many of the soldiers who were part of the operation remarked on it as such, that it felt more like a video game more than what they had been taught to think of as war.

Most recently this trend has arguably continued with the increasing prevalence of drone “warfare” and unmanned aerial vehicles, where warriors are no longer even physically present on the battlefields where they “fight”. It could be argued that in many ways this kind of technological war actually brings the experience of fighting closer to the soldiers controlling the drones, but the point again is the degree to which the fighting of war is now augmented – war by physical and digital means now inseparable.

Computer simulation and wargaming continues to perform a major function in the US military’s preparation for war. DARPA developed a vehicle simulator called SIMNET as early as 1980, and in 1990 SIMNET was integrated into STOW, the armed forces’ “Synthetic Theater of War”, which provides a significant digital component for military exercises.

Wargames and simulations have not only been used by the military in training and strategic planning, but more recently in recruiting. “America’s Army”, a first-person shooter released in 2002, was funded and released by the Army itself, and was explicitly designed to present the modern US Army to civilian youth. The game was created for the specific purpose of depicting an officially sanctioned image of the Army to the public – a exercise in meaning-making in terms of the public’s understanding of the experience of being a member of the armed forces. The fact that the Army chose a video game as a medium is also important; essentially, “America’s Army” functions as a meaning-making training simulator, not only conveying a particular understanding of the armed forces, but preparing potential recruits for the real-life training they might soon experience.

Above, I noted the power of stories in meaning-making and the production and reproduction of cultural understandings. I also noted that games are usually driven, implicitly or explicitly, by narratives. At this point I want to go a step further and argue that games play a role not only in learned meanings but in learned behaviors, and in how we contextualize those behaviors. The fact that simulation is used as an integral part of military training (and psychotherapy) is a strong indicator that it can be an effective tool in terms of shaping behavior and understandings of behavior, as well as the context in which that behavior occurs.

In First Person: New Media as Story, Performance, and Game, Simon Penny explains (parentheses mine):

When soldiers shoot at targets shaped like people, this trains them to shoot real people. When pilots work in flight simulators, the skills they develop transfer to the real world. When children play “first-person shooters”, they develop skills of marksmanship. So we must accept that there is something that qualitatively separates a work like the one discussed above (of an art installation where the viewer can physically abuse the projected image of a woman) from a static image of a misogynistic beating, or even a movie of the same subject. That something is the potential to build behaviors that can exist without or separate from, and possibly contrary to, rational argument or ideology.

This is not by any means to argue that playing wargames will always make someone want to fight wars, any more than it is to argue that playing a FPS will in and of itself make a teenager want to take a gun to school (I think we can all agree that’s a fairly tired argument at this point). It’s merely to point out that simulations have power – power to shape meaning, our perceptions of ourselves and others, and our understandings of our own behaviors, as well as what behaviors are appropriate and reasonable in specific contexts.

So, to make a long post short: there is something particular going on in regards to simulations and wargames in the context of technological warfare in the 20th and early 21st centuries, and especially wargames and simulations that are digital in nature. This something has a tremendous amount to do with the construction of meaning, with behavior, and specifically with our understanding of what wars mean and what it means to fight them.

I want to also note at this point that I’m not out to make any kind of conclusively causal argument. I’m not interested in claiming that video games definitely change how we think of war, or that how we think of war definitely shapes what kinds of games we play, or that either have anything definite to do with how we actually fight the wars we choose to fight. I think any or all of those are interesting arguments, but I also don’t think I have the data to support strong statements about them either way. Instead, what I want to suggest – and what I’ll be employing specific examples in support of – is simply that there’s Something Going On at the intersection of simulation/technology, culture, storytelling, and war, and that this Something is probably worth further thought and investigation.

A primary indicator of a story’s power to shape meaning is its prevalence – how many people are telling it how many times and in what context. It makes sense, therefore, that if we’re going to look closely at what might be happening at the point of intersection I refer to above, we should focus at least in part on war-themed games that have enjoyed considerable popularity.

(I should offer another caveat here: this is by no means and in no way a representative sample. If you wanted to write a truly thorough examination of war-themed video games and American culture, it would take the space of a book to do so. But I think these are revealing cases, albeit a small n.)

Within the genre of war-themed games, very few titles in the last decade have enjoyed the kind of success that the Call of Duty games can claim. The initial entries into the CoD series were set in WWII – as have been many other games – and to refer back to my first post in this series, I think a lot of that can be attributed to how we think of that war. Comparisons can be drawn between WWII games and films, with the themes of noble sacrifice and heroism, and a Manichean standoff between good and evil discussed above. World War II has been described as “the last good war”; this makes it a culturally comfortable reference point for imagining what armed conflict is like.

But CoD‘s most popular titles have been more contemporary in terms of setting – CoD 4: Modern Warfare and its two sequels have been immensely popular, with the first MW selling in excess of 13 million units worldwide. For the purposes of this piece, I’ll be focusing on the first two installments in the series.

Both MW and MW2 put the player in the point-of-view of different soldiers at different points in the story, both US Special Forces and British SAS. Both games also emphasize concepts that are vaguely consistent with what has been calledthe “New War” theoretical approach – the idea that regarding war in the latter half of the 20th and the early 21st centuries, states are less important, and that the borders between state and state, between soldier and civilian, and between state actor and non-state actor are increasingly porous. In both games, the player’s enemy ranges from an insane Middle-Eastern warlord who has masterminded a coup, to the leader of a Russian ultranationalist paramilitary group; in each case it’s understood that the enemy is not a state as such. Indeed, the movements of states often feel abstract and distant from the action in which the player finds themselves involved, however important they might be to the overall plot (indeed, at one point in MW2 the player takes part in a battle between the US and an invading Russian force; however, Russia is invading in retaliation for a terrorist attack perpetrated by Russian ultranationalists and framed on the United States). The player engages in small military operations, fighting against other small groups of soldiers, often to retrieve vital pieces of intelligence or personnel.

Despite the blurriness of combat identities and the de-emphasizing of state-level actors, the actions of the various soldiers that the player personifies are framed by other characters – such as commanding officers – as important, even crucial to the stability of the world. Some of this can be explained through simple narrative convention: in order to engage the player in the story, the player needs to feel that the action in which they are taking part is supremely significant in some way. But some of it also resonates with contemporary understandings of war, with decisive action taking place on a micro rather than a macro level, in small-scale conflicts rather than on massive battlefields between entire armies.

Another thing that makes MW and MW2 so noteworthy is what they suggest about what is permissible in war. MW2 in particular takes a brutally casual approach to the torture of detainees in one scene, where, after you have captured one of the associates of the game’s main villain, you leave him with your fellow team members. As the camera pans away, you see your captive tied to a chair with a soldier looming over him, holding clamps that spark with electricity. While your character does not carry out the torture, the torture is implied to have both taken place, and is implicitly presented as both necessary and reasonable. The game narrative encourages acceptance of this rather than questioning of it, partly because the action proceeds so rapidly from that point that meditation on what has occurred is not really possible. It’s worth noting at this point that game narrative, action, pacing, and design are often difficult to distinguish without doing violence to their meaning; in this case they’re one and the same. A particular narrative interpretation of a particular event is emphasized at least in part because of the mechanics of cutscenes and gameplay.

To turn back to the issue of nobility and sacrifice in war films, it is interesting to compare some of what I discussed in part I of this series with the first two installments of Modern Warfare. Sacrifice in older American war films – particularly death in battle, particularly for the sake of one’s comrades – is regarded as noble, sacred, and not to be questioned. It’s regarded as worthy in itself, and a worthy act by worthy soldiers fighting for a worthy cause at the command of worthy generals and political authorities.

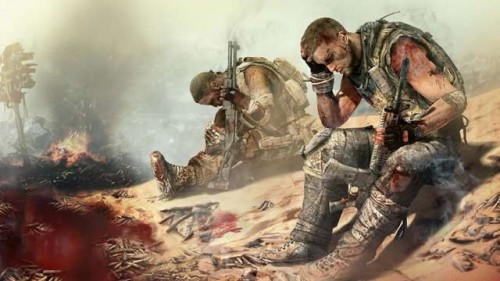

MW and MW2 fall somewhere between war as depicted in heroic war films and in tragic war films. Soldiers, especially the soldiers the player takes on the role of, are presented as competent, well-trained, courageous, and effective, as well as possessing at least a surface-level knowledge of the significance their actions have. When SAS Sergeant John “Soap” MacTavish attacks Russian ultranationalists, he knows that it is because they are seeking to acquire a nuclear missile with which to threaten the US – he further understands that the situation is exacerbated by post-Cold War instability as well as a military coup in an unnamed Middle Eastern nation. When, in the same game (MW), USMC Sergeant Paul Jackson is sent to the Middle East to unseat the author of the coup, he understands that nuclear proliferation is the same threat, and that he and his comrades are literally defending the safety of the world. When, in MW2, you take on the role of Sergeant Gary “Roach” Sanderson and seek to capture a Russian criminal by the name of Vladimir Makarov, you understand that he has authored the instigation of an invasion of the continental US by Russia—while, back in Washington DC, Private James Ramirez literally defends the capital from foreign troops. None of this is in question, and the characters are both informed of their mission’s importance and committed to seeing it carried out. Suffering and sacrifice for the sake of that mission are depicted as noble (though of course, if the player character is killed – with several exceptions that I will address – the game is over). Traditional patriotic values are not questioned in either game.

In MW,when Paul Jackson and his comrades attempt to push through an advancing wave of enemy soldiers to rescue a downed Apache pilot, the player is clearly meant to be moved by their courage and their loyalty to each other. In MW2 the scenes of an invaded Washington DC – complete with a burning Capitol and White House – are clearly meant to be horrific by virtue of being nationalistic symbols that have been injured and destroyed by an enemy force, while the soldiers fighting to push back the invaders are brave defenders of the homeland.

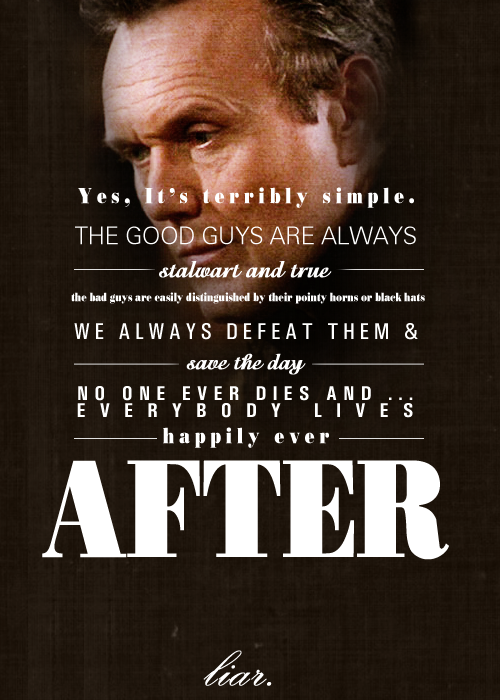

However, where the games both approach tragedy is in their depiction of the essential senselessness in war, and of the betrayal of soldiers by their commanders. In Modern Warfare, Sergeant Paul Jackson succeeds in rescuing the downed pilot, only to have his own helicopter brought down by the shockwave and ensuing firestorm when the warlord in charge of the country detonates a nuclear bomb. In one of the most haunting – and unusual – sequences of the game, the player crawls from the wreckage of the helicopter, struggles to his feet, and looks around at a burning nuclear wasteland before dying of his injuries. There is no way to survive the level, no weapons to wield and no one to kill, and not even really anything to do but to exist in that moment and bear witness to horror before expiring. The way the narrative frames the sequence is fairly clear: Paul Jackson is a heroic man engaged in a worthy fight, and yet the tragedy of his death is that it’s fundamentally senseless.

Likewise, at the end of his last successful mission to one of Makarov’s safehouses, Sergeant Gary “Roach” Sanderson is brutally murdered by his commander, Lieutenant General Shepherd, who is revealed to have been using Roach and his comrades for his own ends. Again, there is no way to survive the episode; the betrayal of a soldier by his commander is part of the story and cannot be avoided. The plot element differs from much of what one finds in tragic war films in that both the soldiers on the ground and the ideals for which they fight are depicted as essentially honorable; it’s the men in power who should be questioned and held up for suspicion.

This last is especially telling, given a number of the dominant narratives that have emerged out of the Iraq War – that of American troops acting in good faith but betrayed by negligent and/or greedy politicians and commanders. In that sense, Modern Warfare is folding one narrative into another in a kind of shorthand; by now, this is a story with which we’re all familiar on some level, which makes it available for the game’s writers to use in a play for the player’s emotions. Deeper characterization isn’t necessary; you never really get a clear sense of who any of these people are. Deeper understanding of the geopolitics behind what’s happening is likewise de-emphasized; though the actions of the player’s character might be of immense importance and the character himself seems to understand why he’s been given the orders he has, all the player really needs to know is that they’re important, not why they’re important. The cultural shorthand of “betrayed soldier” is all that really matters, and once it’s been employed, the game can and does move on.

It’s important at this point to examine the question of choice, and how choice is understood to function within video games, particularly games about war. Choice in gaming has become something of a selling point; witness the proliferation of sandbox games, as well as games that at least attempt to present the player with some kind of narratively meaningful moral decision-making (see Bioshock and Bioshock 2). But what’s interesting about games like Modern Warfare is what they suggest about the choices that a player doesn’t have.

Someone who plays a video game is interacting with a simulated world, and the rules of that world dictate what forms of interaction are possible with which aspects of the game world. Game code determines how a player moves, what they can touch and pick up, what they can eat or use as tools—and what they can injure or kill or destroy. This is additionally significant because when a certain action is permitted on a certain object, code—the rules of the game—often dictates that it is the only action that can meaningfully be performed on that object. An object in the game world that can be consumed can frequently only be consumed; there is no other possible use for it. Likewise, a character in the game world that can be killed can often only be killed; with exceptions, they cannot be talked to, reasoned with, or negotiated with, and inaction on the part of the player usually leads to the player’s demise and the end of the game. Especially in combat-themed first person shooters, the rules are often quite literally as simple as “kill or be killed”, and regardless of danger to one’s character, destruction of some kind is commonly necessary to advance the game action. War as depicted in video games is therefore war without real agency: fighting and killing an opponent is the only rational or reasonable course of action, if not the only one even possible. Game code is not neutral; it tells a story, it sets constraints on how that story can be interpreted, and it determines what forms of action are appropriate or intelligible.

The thing for which Modern Warfare 2 is probably best known is the infamous “No Russian” level. In this level, the player has infiltrated a group of Russian nationalist terrorists who plan to open fire on civilians in an airport. They then do just that – and the player cannot stop it. They can take part in the slaughter or they can stand by and do nothing, but they can’t save anyone, and they can’t fire on the terrorists. The player is therefore being explicitly put in a position where agency is poignantly lacking (recall the nuclear wasteland level in MW), where civilians scream, beg for mercy, and attempt to crawl away, all while the player can do nothing narratively meaningful.

But the player can still shoot. The fact that they’re holding a weapon and can make use of it is significant in itself – there is agency, just agency of a particularly horrible kind. Mohammad Alavi, the game designer who worked on No Russian, explains it this way:

I’ve read a few reviews that said we should have just shown the massacre in a movie or cast you in the role of a civilian running for his life. Although I completely respect anyone’s opinion that it didn’t sit well with them, I think either one of those other options would have been a cop out… [W]atching the airport massacre wouldn’t have had the same impact as participating (or not participating) in it. Being a civilian doesn’t offer you a choice or make you feel anything other than the fear of dying in a video game, which is so normal it’s not even a feeling gamers feel anymore…In the sea of endless bullets you fire off at countless enemies without a moment’s hesitation or afterthought, the fact that I got the player to hesitate even for a split second and actually consider his actions before he pulled that trigger– that makes me feel very accomplished.

Essentially, the player can’t prevent horrible things from occurring. The most they can reasonably expect is to choose to participate in those things – or not. But when player agency is whittled down to that level, player responsibility also erodes; why should there be any sense of responsibility, given that one is playing in a world where the parameters have been narrowly set by someone else?

A more recent game that has some serious points to make regarding player agency is Spec Ops: The Line, a contemporary rehashing of Apocalypse Now, (which is itself of course a retelling of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness). Gaming writers have noted that it’s a game that seems to have active contempt for its players, drawing one in to thinking it’s a fast, flashy, Modern Warfare-style shooter before pulling the rug out and revealing to the player that every action they’ve taken since the game’s beginning was in fact utterly reprehensible. It’s a game that purports to be a giant comment on its own genre, and its success in doing so has apparently been mixed.

But one primary thing on which Spec Ops seems to comment is the question of what choices a player actually has in a war game – and, by extension, what choices a person has in a scenario like the one the game depicts. The player, the game seems to be saying at multiple points, has no choice; by choosing to play the game at all – by choosing to enter the scenario – they’ve locked themselves into a situation where not only is there no real win-state, but there is no inherent significance to any of their actions. The game – and the world – is not working with you but against you. Walt Williams, Spec Ops‘s lead writer, puts it this way:

There’s a certain aspect to player agency that I don’t really agree with, which is the player should be able to do whatever the player wants and the world should adapt itself to the player’s desire. That’s not the way that the world works, and with Spec Ops, since we were attempting to do something that was a bit more emotionally real for the player…That’s what we were looking to do, particularly in the white phosphorous scene [where a group of civilians is mistakenly killed], is give direct proof that this is not a world that you are in control of, this world is directly in opposition to you as a game and a gamer.

Video game blogger and developer Matthew Burns takes issue with this, pointing out that the idea of the removal of choice leading to a massacre of civilians has intensely troubling implications, not only for games themselves but for how we as a society understand the question of choice in extremis:

I present a counter-argument: in the real world, there is always a choice. The claim that a massacre of human beings is the result of anyone– a player character in a video game or a real person– because “they had no choice” is the ultimate abdication of responsibility (and, if you believe certain philosophers, a repudiation of the very basis for a moral society). It is unclear to me how actually being presented with no choice is more “emotionally real,” because while it guarantees the player can only make the singular choice, it is also more manipulative.

This, then, is what I think is the central question around video games, simulation, storytelling, and war: How do we understand the very meaning of action? How true is it that we always have a choice, and if we do – or don’t – what does that mean for responsibility, on the level of both individual and society? I argue that when we play games, even if we’re not playing very close attention to the story – even if there isn’t really very much of a story to speak of anyway – we still internalize that story on some level. We interpret its meanings and its logic; we have to, in order to move within its world. We are participants on some level, even if the extent of our participation is the experience of the gameworld. And when we’re participants in a story, that lends the story greater weight for us than if we’re merely passive observers – to the extent that one can ever be passive within the space of a story.

Like other forms of media, war-themed video games are arenas for reproductions of certain kinds of meanings and narratives about our culture and our wars. But more than that – and perhaps more than other forms of media – they are spaces for conversation and debate over how we process those meanings, and what it truly means to participate in something. In these games we talk about patriotism, honor, and sacrifice. But we also question ethics, choice, and the significance of death – and we as participants are brought uncomfortably close to those questions, not only in terms of the questions themselves, but in terms of what it means to ask them at all, and in the ways that we do. And as Spec Ops and No Russian reveal, many of the answers we find are intensely troubling. As Matthew Burns writes:

I played through No Russian multiple times because I wanted direct knowledge of the consequences of my choices. The first time through I had done what came to me naturally, which was to try to stop the event, but firing on the perpetrators ends the mission immediately. The next time I stood by and watched. It is not an easy scene to stomach, and I tried to distance myself emotionally from what was going on.

The third time, I decided that I would participate. I could have chosen not to; I could have simply moved on then, or even shut off the system and never played again. But a certain curiosity won out– that kind of cold-blooded curiosity that craves the new and the forbidden. I pulled the trigger and fired.

Also highly recommended: