In 2006, the body of Joyce Carol Vincent was found in her apartment. The TV was still on and she was surrounded by unwrapped Christmas presents.

She had been dead for three years. No one had noticed.

This might seem like odd subject matter for a game, but in fact a game was planned around it, to coincide with the release of a documentary about Vincent entitled Dreams of a Life. I finally watched it last night and then, as I often do when I watch movies that affect me strongly on an emotional level, I went looking for more information. What I found was a Kotaku article from last year that tells the story of the development of the game, a story that ultimately ends in (partial) failure. What interests me, aside from how astonishing it is to me that someone would even try to make a game about Vincent’s life and strange death, is why the game failed in the end.

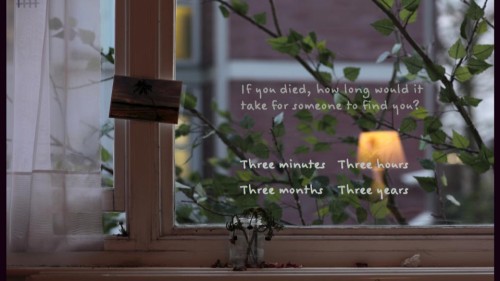

Most obviously, of course, it’s heavy subject matter that touches on some of the social facts that generate tremendous anxiety and fear for a great many of us – for the same reason that Vincent’s story struck a chord for so many people when it became known. Who are my friends? How close are we, really? Will they remember me when I’m gone? Will they even notice? If I was hurt or in trouble, how many of them would help me? Just how expendable am I in their eyes? Will I someday be completely alone?

But the primary reason why the game failed is actually much simpler and more fundamental: Games aren’t (currently) structured in a way that allows for an effective story to be told about something like this, and that structure has as much amount to do with the assumptions that we bring to the medium as the objective structure of the medium itself. More specifically, the kind of storytelling that the subject matter seemed to call for would fail in its intended effect the second that the player started thinking of it as an actual game.

The idea behind the game was that players would be brought face to face with some of the questions listed above and would be offered the chance to connect something of theirs to a person in their past – which, it quickly became clear, just wouldn’t work. Basically, as designer Margaret Robertson explained:

We were confident that posing those questions would get people to think about things they’re not usually thinking about. The problem was that, the minute we enclosed them in a game structure, we tainted their answers. Even if this is a game that isn’t about winning or losing or dying or enemies or anything like that, the minute you understand that your progress is being impeded and that your inputs and choices are going to free that progress, you want to free that progress. We can’t not want that. So the minute you say: ‘Who do you want to give the ring to?’ I’m thinking, ‘Well, shit, what does the game want me to say here?’

This reveals something significant about the logic behind games, and, more generally, how we interact with most forms of technology – and how that menu of interactions is limited to what we can imagine. We understand games as fundamentally puzzles, albeit puzzles with potential narrative significance. Puzzles need solving. Solving them allows for progress through the game; we unlock more content by successfully completing certain tasks. When we’ve solved everything and progressed as far as we can, we’ve won the game.

In other words: Games, by definition, have winstates. And we expect them to. The instant we’re engaging with a game, we’re instinctively trying to discern what the winstate is and how we can reach it.

This is true even of games that are intended to be experiences of a created world as much as they are puzzles – games like Myst, and more recently That Game Company’s Flower and Journey. We’re still trying to do whatever it is we need to do in order to progress through the world. Journey is probably one of the most emotional games I’ve ever played, yet it’s still made up of a series of puzzles.

So what we’re dealing with here is actually one of the limits inherent in games: The point at which winstates stop being the goal and start becoming distractions. Because it’s still very hard for most of us to shed the fundamental assumption that they are the goal.

This becomes especially problematic when what we’re doing to achieve the winstate is objectively kind of horrible. I’ve heard it observed that when you kill a character in a shooter, you’re not really killing someone in your head – even someone fictional, and as I’ve argued before, fiction is a significant component of reality – so much as you are solving a puzzle. Killing someone is just what you need to do in order to progress through the game; in Call of Duty, you kill a bunch of dudes to get to the next area so you can kill a bunch more dudes, and so on ad nauseum. If you want to, say, tell a story about exactly what it means to commit murder on this scale, the emotional and ethical weight of those murders is still going to be diminished by what it actually means to kill in the context of a game. By what we assume it means.

Some games have commented on this pretty effectively by questioning precisely what it means to kill in this way with this level of significance. Spec Ops: The Line, for example, gives the player the standard kill-dudes-next-area-kill-more-dudes shooter experience and then turns around and heaps abuse on the player for doing exactly what the game constrains them into doing, as well as on the very assumptions with which we all engage with shooters. It’s a game that actively hates itself for what it is and hates the player for playing it. It knows why its own structure and relationship with a player constrain the kinds of stories that can be told and the kinds of actions that can be performed. It’s not trying to break out of those limitations; it’s questioning whether a breakout is even possible.

Our actions are naturally constrained by what we perceive as not only appropriate but possible. We can’t do certain things with certain technologically mediated forms of storytelling because there are limits to what users can imagine within the context of those media. What I want to emphasize here is that this is a very real problem for anyone trying to do anything innovative with design; too innovative, too unfamiliar, and the user won’t possess the baseline assumptions, imaginings, and understandings necessary to experience the medium in the way the designer intended. This is a particular problem with operating systems, as the backlash to the rollout of Windows 8 reveals. Even if people can figure out a new thing, they might not find it a comfortable space to be in if that space doesn’t conform to their expectations of what that space can and should be like. Having to expand the bounds of what one expects is not always – if ever – a pleasant experience. And sometimes it simply can’t be done.

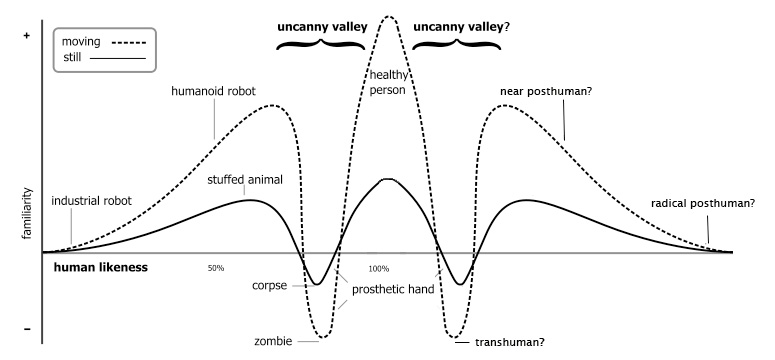

But I want to return to storytelling in particular, and especially about what it means to tell stories with emerging forms of technology, with things that are still arguably in flux. Computer and video games are still very much a new medium; we’re still figuring out what they can even do, and there’s been a lot of debate around what’s really possible. Our perceptions of what’s possible tend to be persistent; with visual media, there are certain assumptions coded within different forms, and when there’s a mismatch between those assumptions and what the artist is using them to do, the effect can be jarring.

Our assumptions about how to engage with different technologies will almost certainly expand along with how we use them (and in many ways changing assumptions will probably be the driving force behind new kinds of use). We’ll probably see a day when games aren’t defined by winstates. In the meantime, however, death can only mean so much.

Sarah confronts the narrative limitations of 140 characters on Twitter (@dynamicsymmetry)