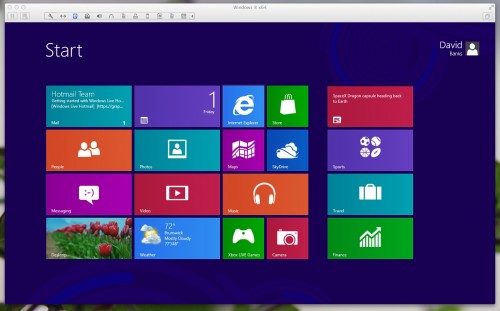

My first PC was a frankenstein PC running Windows 3.1. I played Sim City and argued with people in AOL chat rooms. My first mac was a bondi blue iMac that ran OS 9, more AOL, and an awful Star Trek: Voyager-themed first-person shooter. I was 13. In the intervening years, I’ve had several macs and PCs, all of which have seen their fair share of upgrades and OS updates. Even my current computer, which is less than a year old, has seen a full OS upgrade. I am one of those people that like radical changes to graphic user interfaces (GUIs). These changes are a guilty pleasure of mine. Some people watch trashy television, I sign up for a Facebook developer account so I can get timeline before my friends. I know I’m fetishizing the new: it goes against my politics and my professional decorum. I have considered switching to Linux for no other reason than the limitless possibilities of tweaking the GUI. It is no surprise then, that I have already downloaded the Windows 8 release candidate and I am installing it on a virtual machine as I write this paragraph. What is it about GUIs that evoke such strong emotions? While I practically revel in a new icon set, others are dragged into the future kicking and screaming. What is it about GUIs that arouse such strong feelings?

I think the easiest answer lies in the “desktop” metaphor. We arrange the world around us to suit our needs. If someone were to come into your home and rearrange your office furniture, you would feel confused but also violated. When someone takes control over something we hold as intimate, we feel infringed upon. Something that should be under our personal control has been altered without our explicit consent and that makes us feel vulnerable. But Facebook and Windows are corporate properties, not our physical homes. Why would we develop similar feelings for a Facebook page and a room in our house? If you’re a regular reader of the blog, you know part of the answer: Our online and offline lives are enmeshed in an augmented reality. Digital dualism, the a priori assumption that offline interaction is inherently better or more “real” than online social activity, would have us search for some kind of antisocial proclivities. We are developing emotional ties with inanimate objects that should only be reserved for fellow humans. We are too wrapped up in superficial and meaningless relationships with gadgets and machines that we care more about iOS 6 than the human rights atrocities in Syria. These are both straw man arguments that have little baring on how humans relate to each other and inhuman objects. When we get outraged over a new interface (or, in my case, desperately await their arrival) we may have aesthetic objections (like this person and this person) but these are always couched in a functionalist argument. Just about every complaint about a major GUI redesign is a variation of the following:

The new design makes it difficult to do some things and makes less useful tasks easier to accomplish. The old design allowed me to do X very easily, in the new design X is removed/hidden/unrecognizable and I no longer know how I am going to use this product.

There’s also a lot of speculation surrounding the designers’ intellectual capacity and a fair amount of cursing.

Returning to the question I posed above: Why get bent out of shape about something that you should you develop strong feelings about the arrangement of pixels that you don’t even own? The answer has two parts. First, ownership is a fickel concept. Social media accounts do not square with the property ownership regime in which we find ourselves. You can opt to download the data of your Google account of Facebook profile, but that’s not the same. Your profile is more than the sum of its data. The EULA might say everything belongs to the company, but you are your profile. Changing your desktop experience or your profile layout is tantamount to some stranger running up to you and giving you a haircut against your will. Similarly, cloud computing and desktop emulation have been around for quite a while, and yet -all things being equal- I would choose to work on my small laptop over a spacious public access desktop any day of the week. You will also notice this at conferences. Given the option, most people want to use as much of their own stuff as possible for their presentation. I say “stuff” because, while its usually a digital hardware and software preference, I have been to conferences where someone whipped out some overhead transparencies and asked for a projector. This sort of behavior reminds us of a second definition of ownership: a synonym for responsibility. You want your presentation to go well, you’re responsible for your own performance, and so ownership (the first kind) over the presentation hardware might make you feel like you’re in control. The familiar is safe, and we like to feel safe when we put ourselves on display- whether at a conference or on Facebook.

This brings us to the second part of the answer: the desktop metaphor is becoming less and less accurate. We still use our computers to do “desk-like” things –writing, editing, and calculating– but we also talk to people, compose music, watch movies, and purchase goods and services. The computer has become an entire city, complete with movie theaters, music venues, markets and wide open public spaces. We give product reviews to each other, share family photos, and tell jokes to each other. When the interfaces that mediate these social activities change, it is a jarring experience. Imagine if your home town were totally rearranged tomorrow. You are used to the old design and had all of the shortcuts memorized. Now the back alleys and keystrokes are different and you have to memorize new ones all over again. This actually happens in the physical world, but it is usually in the wake of a major disaster.

This is a very social way of looking at information technology. The designers, as far as I can tell, still see interface design as a personal and individual experience. Sam Moreau, Microsoft’s User Experience Director gave an interview to Gizmodo back in February. I found this part particularly telling:

Giz: What has the negative feedback been like? What do people not like?

SM: To be honest, you know what I think it is? When you change something—this is my own personal observation—a lot of us know how the PC works, become the help desk for all of our friends and family. Inherent in that is a sense that I know. I’ve got this expertise now, I’ve got this power. We’ve changed something now, and leveled the playing field for all those personal help desks, so they’re no longer the guy. It’s human nature—I had invested in this, I knew this, and some degree of my self was aligned to the fact that I know how this stuff works. I do think that’s an aspect of what’s going on.

Giz: Do your friends come to you and tell you, this is what I want Windows to look like? What’s the craziest request?

SM: Last night at dinner. A friend of mine said, “Look it’s all great and everything. But I need you to make the fonts a little bit bigger. My eyes are getting older, so just make them a little bit bigger for me please.”

Giz: But the fonts are huge.

SM: You’re not the only one who uses it, it turns out. That type of stuff. I’ll get that from uncle who’ll call me. “It’s pretty hard to read. Could you make the button a little bigger? ” All the time.

JLG: Steven does this talk, mostly about Office, about how it’s like ordering pizza for a billion people. Some people are lactose intolerant. Some people don’t like mushrooms. Now make everyone happy.

SM: There’s a billion people, and pizza’s your only option. That’s what it’s like designing Windows.

I have been a help desk in formal and informal capacities for most of my life. I know lots of people who serve this function as well. I do not know of a single person that dreads the day when their dad will stop asking them computer questions. Maybe it is “an aspect of what’s going on” but there is something much bigger, much more fundamental, going on.

The pizza metaphor is an interesting one, but something designers do all the time. From buildings to coffee makers, one of the biggest challenges of designers is to make something that lots of different people can use. Granted, operating systems are incredibly complex things that must accomplish a wide range of things with relative ease, but then pizza is a terrible metaphor. A pizza is simply consumed. Consumption does not begin to describe what is happening when we use a computer. I agree with David Graeber when he says,

One thing I think we can certainly assert. Insofar as social life is and always has been mainly about the mutual creation of human beings, the ideology of consumption has been endlessly effective in helping us forget this. Most of all it does so by suggesting that (a) human desire is essentially a matter not of relations between people but of relations between in- dividuals and phantasms; (b) our primary relation with other individuals is an endless struggle to establish our sovereignty, or autonomy, by incorporating and destroying aspects of the world around them; (c) for the reason in c, any genuine relation with other people is problematic (the problem of “the Other”); and (d) society can thus be seen as a gigantic engine of production and destruction in which the only significant human activity is either manufacturing things or engaging in acts of ceremonial destruction so as to make way for more, a vision that in fact sidelines most things that real people actually do and insofar as it is translated into actual economic behavior is obviously unsustainable. (“Consumption” in Current Anthropology Volume 52 Number 4 August 2011)

In other words, the fact that we purchase (consume) computers is only the beginning of our interaction with them, and it isn’t even the most interesting part. We socialize with and through them. The fact that there are many people doing similar things on computers, gives those computers a new meaning and function. (The internet is useless if there’s only one person on it.) What would an explicitly socially designed computer look and act like? I offer this only as a provocation, I have no speculative answers at the moment. I only suspect that drastic GUI changes would be less likely, and here’s why:

Drastically changing an interface makes us uncomfortable because we are experiencing a simultaneous phenomenological change in both our environment and our digital selves. This hints at the possibility that, one of the few things that are truly different between online and offline social activity is that the environment and the self are entangled to the point that they are almost indistinguishable. Our profiles and desktop environments are extensions of ourselves, but the sum of these individual parts constitute a digital public space. This is another reason why the “end of privacy” debates are so ridiculous. Privacy is not disappearing, rather the relationship between the public and the private is being redefined along entirely new boundaries. It is also why studying social activity in digital worlds is so important- fundamental assumptions about the embodied nature of social activity must be called into question. To write off social media as unimportant or anything less than society-formation (for better or worse) belies a significant underestimation of what humans are capable of achieving. Namely, we are not just playing with digital toys, we are investigating new potentialities of what it means to be human.

I suppose it is no coincidence that I also enjoy looking at construction sites, own an eclectic wardrobe, have a couple of tattoos, reorganize my office furniture at least once a year, and get dramatically different haircuts. I appreciate the process of change to both the environment and the self. Interfaces are another aspect of this preference. With each new forced iteration of Facebook, I find myself enjoying the proces of planned obsolescence. Some prefer keeping things the same. There are politically normative critiques of both, neither of which I am prepared to discuss at any length in this post. Instead I will simply say that I am enjoying my Windows 8 experience and contemplating getting a haircut.

David eagerly awaits changes to Twitter, Tumblr and Facebook. He regularly changes the entire style layout of davidabanks.org

Comments 8

Dan Greene — June 1, 2012

This is a lovely little essay David. Great read! I think the app economy and accompanying HCI principles (modular, single-use buttons) push the consumption story even further.

I've always wondered what the world would've been like if the guys at PARC or wherever had somehow settled on an HCI metaphor less blatantly middle-class professional than the desktop. What about a city street with branching avenues, or a shop floor with parallel work flows that meet at the end, or a church with a central attention-space, lots of marginal detail, and time-shifting application accessibility. You write what you know, though, so the desktop might've been inevitable.

David Banks — June 1, 2012

Thanks Dan.

That's an excellent question about PARC. There's a decent book out there written by two PARC alums, John Seely Brown and Paul Duguid called "The Social Life of Information". I haven't read the whole thing, but it actually takes a much more social perspective to HCI than you'd think:

http://www.firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/issue/view/118

sally — June 2, 2012

Great piece, David. Fun to read, too.

We talk about the need to change user interface metaphor, in our paper "PolySocial Reality: Prospects for Extending User Capabilities Beyond Mixed, Dual and Blended Reality." In it, we discuss ways that developers can use PolySocial Reality (PoSR) to represent a more complete complex structural model of individuals interacting within multiple environments. Of particular note, would be our table of Actor/Technology Interaction Cases where we illustrate where the dev model has been and where it needs to and will eventually be going.

"Polysocial Reality: Prospects for Extending User Capabilities Beyond Mixed, Dual and Blended Reality" can be found here.

http://www.dfki.de/LAMDa/2012/accepted/PolySocial_Reality.pdf

Linkness. What we’ve been reading | June 8, 2012 | NEXTNESS — June 7, 2012

[...] is tantamount to some stranger running up and giving you a haircut against your will” | CyborgologyOn Nextness this week.10 things Junior’s loving right now. | NEXTNESSTEDxSydney 2012: Third [...]

My Breakup With Facebook: a reflection » Cyborgology — July 6, 2012

[...] them had to do with changes to Facebook’s interface with which I had aesthetic issues (yeah, it did mean that much to me) while some of them had to do with other gut-level issues. But after having spent this long away [...]

Nein Quarterly – — June 7, 2014

[…] relevant to Jarosinski’s point is this post from David A. Banks over at Cyberology, in which he theorizes that we become attached to user interfaces because so much of our lives […]