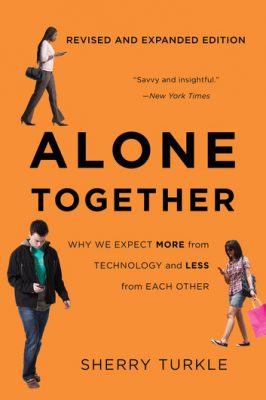

It’s been 7 years since Alone Together (2011) was published. And, here at Cyborgology (which we launched only a few months before the book came out), probably no other publication has received so much of our attention (with the possible exception of Haraway’s “Cyborg Manifesto.”

While Turkle’s earlier writings were hopeful, forward-looking provocations about the growing intimacy between humans and machines, Alone Together (as well as Turkle’s more recent Reclaiming Conversation [2015]) struck a completely different tone: a present-focused techno-pessimism. Turkle’s insistence on the intrinsic inferiority of digitally mediated interaction—that it is less real, less human—became a foil for ambivalent, nuanced analysis of technology and society that we sought to provide on this blog. In part, Turkle has become an antagonistic figure because she cherry-picks anecdotes while ignoring more systematic research on the way digital technologies facilitate social support. In part, because she epitomizes a sort of rhetoric about the ontological inferiority of the Web—its lack of realness—that has distracted from important social justice questions about how such technologies reinforce/reproduce existing inequalities and the concrete measure that can be taken to changes this.

In the recent 2017 update of the book. Turkle doubles down, referencing Darwin and embracing evolutionary biology style grand narratives in her new preface. She says, “as we evolved, people were the only other creatures who responded with us with suggestions of empathy.” (I can hear Haraway off in the distance, shouting, “what about dogs?!”) Turkle continues:

Now robots showed us “as-if” empathy, and we were, you might say, cheap dates. We proved willing to talk to robots about personal matters.

She explains that machines gain control over us because they know how to “push people’s Darwinian buttons.”

This new analysis is also more polemical than the original book, which she now describes as “a call to arms.” For example, one passage reads:

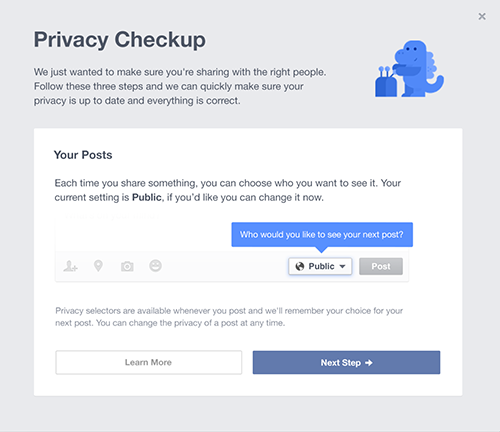

What is democracy without privacy? What is intimacy without privacy? If your answer is, Let’s wait and see; technology always brings change, and people always adjust, then my note to you is this: you are playing with fire.

I suppose it should be said that this is a false dichotomy. There is a lot daylight between fearful techno-determinism and the wait-and-see approach. We could, for example, talk about (re-)constructing social media platforms so that they are not incentivized to collect and sell our data.

In her new take on Alone Together, Turkle’s most grave concern now appears to be that technology is undermining our capacity for empathy altogether, particularly for children as their toys become smarter. Furby and Tamagatchi were central to the original book, but their capacities pale in comparison to the high tech toys of today—at least, for those who can afford smart toy.

new questions feel… pressing: How will intimacy and empathy change in a world where we give toddlers baby bouncers and potty trainers with a slot for a tablet or smart phone?

I’m no technophile. It’s never even occurred to me to setup a television for my toddler let alone a tablet. But, I can say categorically that biggest threat to intimacy my son and I share isn’t the distraction of technology but the distraction of economic precarity, the endless hustle of the gig economy—something that Turkle, who begins the preface by informing readers that she is writing “at the cottage,” likely has little experience with.

Despite the fact that I think almost everything Turkle says is reductionist and oozes with privilege, I like her new style. She’s more upfront with her ideological agenda and the writing is far clearer as a result.

Authenticity and Intimacy in Alone Together

Turning now to the original text of Alone Together, I’ve sought to examine Turkle’s core arguments about intimacy and authenticity as carefully and generously as I could construct them. These terms come up a lot throughout the book and often in relation to one another. Being interested in digitally-mediated intimacy, I wanted to parse what she meant by both.

What’s most clear is her concern that technology is replacing “real” intimacy with simulation. She explains that the purpose of her book, Alone Together (2011, p.12), is to explore

a nagging question: Does virtual intimacy degrade our experience of the other kind and, indeed, of all encounters, of any kind?

Turkle’s nagging question itself raises a couple questions: What does she understand intimacy to be and what distinguishes “real” intimacy from its virtual or simulated forms—in other words, what conditions are necessary for intimate relationships to be authentic? But, while she emphasizes the centrality of these concepts to her work theorizing technology—saying, for example (p. 6), “both by temperament and profession, I place high value on relationships of intimacy and authenticity”—she never systematically defines these terms, so we are left to piece together how she interprets them.

For Turkle, authenticity is the opposite of simulation—in particular, she contrasts authentic interactions with “robotic sociality” (i.e., humans interacting with robot or interacting with each other as though they were robots). From children’s toys to sex dolls, Turkle contends that there is a growing propensity in our culture to replace people with interactive machines in important social interactions. She (2011, p. 7) explains why she believes such interaction is inauthentic:

Authenticity, for me, follows from the ability to put oneself in the place of another, to relate to the other because of a shared store of human experiences: we are born, have families, and know loss and the reality of death. A robot, however sophisticated, is patently out of this loop.

The way Turkle defines it, authenticity involves a certain imaginative capacity to assume the role of the other. In other words, authentically human interactions are defined by empathy. She justifies this claim in the 2017 preface mentioned above, leaning on speculative evolutionary biology: “as we evolved, people were the only other creatures who responded with us with suggestions of empathy.”

Robots (or AI, more broadly) can only mimic empathy (what she calls “as-if empathy” [2017]), they cannot actually feel it. And, though they can perform I ways that seem to invite empathy from us, that empathy is misplaced since we are projecting feeling on to robots that they can actually have. In her (2011, p. 287) words:

That the robotic performance of emotion might exist in its own category implies nothing about the authenticity of the emotions being performed. And robots do not “have” emotions that we must respect. We build robots to do things that make us feel as though they have emotions.

The consequence, Turkle fears, is that robots actually condition us away from empathy, because they can simply be turned off when inconvenient. In fact, the thrust of her book is, ultimately, to argue that the kinds of simulated sociality we have with robots extends beyond those interactions to interactions between people. She explains (2011, pp. 12-13):

Sociable robots and online life both suggest the possibility of relationships the way we want them. […] From the perspective of our robotic dreams, networked life takes on a new cast. We imagine it as expansive. But we are just as fond of its constraints. […] Technology makes it easy to communicate when we wish and to disengage at will.

We are encouraged to see each other like robots—something there when we need it but that we can ignore or turn off when we do not—that digital communications technology

puts people not too close, not too far, but at just the right distance. The world is now full of modern Goldilockses, people who take comfort in being in touch with a lot of people whom they also keep at bay (2011, p. 15).

She suggests that this willingness to distance others is dehumanizing, contrasting the easily avoidable/escapable interactions we have with intelligent machines to the “messy, often frustrating, and always complex world of people” (2011, p. 6). Turkle fears the outcome of these interactions with interactive technologies will be “an emotional dumbing down, a willful turning away from the complexities of human partnerships—the inauthentic as a new aesthetic.”

In other words, interactions with robots teach us to treat others as objects that can be disregarded or ignored. Authentic sociality, on the other hand, requires us to acknowledge the personhood of others and to confront them in a way that we cannot easily escape. In phenomenological language, other people are not merely an “object for-us” but a “subject in-itself.”

Ironically, however, Turkle seems to play down precisely the complexities of being human that she purports to champion. Her valorization of evolutionarily-driven, pre-social, “authentic” humanity seems to leave little room for the multifaceted, contradictory, and performative self that social theorists from Goffman to Gergan to Butler have observed. On the other hand, she often acknowledges that identity is malleable, and its development requires play and experimentation. Technology’s capacity to facilitate identity play was, in fact, a focal point of her earlier books, and it is something she continues to champion, even as she grows more pessimistic that technology affords such play. “The Internet can play a part in constructive identity play, although, as we have seen, it is not so easy to experiment when all rehearsals are archived” (2011, p. 273).

How do we make sense of Turkle describing authenticity as an essential aspect of our evolved human nature and at the same time describing identity as a fluid process? The simple answer seems to be that—in contrast to the way we commonly use the term—“authenticity,” for Turkle, is not about identity; instead, it is largely synonymous with empathy. Robots are not authentic because they are not empathetic. Humans are authentic to the degree they exercise empathy. But, none of this is meant to be a statement about identity in the way that we usually talk about authenticity.

But, wait… Just when we thought we understood where Turkle was coming from, she throws us a curveball. She cites this conversation with a teenager as emblematic of the way in which digital communications threaten to authenticity (2011, p. 271)

Brad says that digital life cheats people out of learning how to read a person’s face and “their nuances of feeling.” And it cheats people out of what he calls “passively being yourself.” It is a curious locution. I come to understand that he means it as shorthand for authenticity. It refers to who you are when you are not “trying,” not performing. It refers to who you are when you are in a simple conversation, unplanned.

Here, Turkle seems to be offering a second and third definition for authenticity: the unperformed self and the unmediated self. Moreover, she reinforces this second definition of authenticity as the unperformed self in her (2016, p. 109) book, Reclaiming Conversation, saying that: “Instead of promoting the value of authenticity, [social media] encourages performance.” This is the only mention of authenticity in her newest book.

Clearly these are distinct definitions of authenticity. Are we meant to assume that some underlying conceptual thread links them all together? Or, are these different definitions the product of conceptual slippage?

One possible way we might reconcile her statements regarding the inauthenticity of the performed self with her celebration of identity exploration is to infer that she believes that identity play is good when it is self-focused and problematic when it is other-focused; however, I am dubious as to whether such a distinction can hold up in practice. Phenomenology dating back to Hegel, existentialism, and social psychological theories such as “the looking glass self” all point to the significance of others in coming to know the ourselves. In other words, we often perform identities for others because we want to know ourselves.

I think the most generous interpretation is that Turkle intended for the first definition of authenticity—“the ability to put oneself in the place of another, to relate to the other because of a shared store of human experiences”— to be the meaning of the concept throughout Alone Together; however, because this is such an unusual way to use the term, she occasional slips into the more common usage.

More cynically, I would suggest that her choice to use this term was a rhetorical move that allowed her to condemn digitally-mediated interaction by association (with inauthenticity) rather through argumentation. In other words, you do not have to do the work of explaining why digitally-mediated interaction is bad if you define it as inauthentic, because the inauthentic is already assumed to be bad. Slippages in how the term “authenticity” is used then serve to reinforce this negative association.

Nonetheless, if we bracket these other meanings for authenticity and focus on her unique definition, then we can uncover how it is connected to another key concept in the book: intimacy. If authentic interactions are defined by empathy, then intimacy is the product such interactions. While she sometimes describes “intimacy with machines” (2011, p. xxiii), she clearly signals that such intimacy is inferior, lacking reciprocity. In other words, authenticity is a precondition for “real” intimacy and simulation anathema to it.

This brings us to what I believe is the underlying thesis of the book—that technology threatens intimacy by undermining authenticity—which is alluded to in the opening sentences (2011, p. 1):

Technology proposes itself as the architect of our intimacies. These days, it suggests substitutions that put the real on the run.

These substitutions may be robots, computer programs, or smart toys like Tamagotchi and Furby. But the substitutions that concern Turkle are those that occur between humans. As I have already decribed, her central fear is that simulated interactions with smart machines condition our expectations for interactions with other humans, especially as technological mediation constructs interactions between humans in ways that look more like interactions with machines. Specifically, with regard to intimacy, she (2011, p. 16) explains that:

when technology engineers intimacy, relationships can be reduced to mere connections. And then, easy connection becomes redefined as intimacy.

In other words, for Turkle, real intimacy requires both availability and commitment. Digital technologies are problematic insofar as, even though they may bridge distance, they also make it just as easy to disconnect. We are not required to confront the consequences of interactions, to literally see the impact of our words on the face of another. For Turkle (p. 288), real intimacy requires “about being with people in person, hearing their voices and seeing their faces, trying to know their hearts.”

In contrast, she (2011, p. 169) believes that, with “online intimacies, we hope for compassion but often get the cruelty of strangers.” In fact, she suggests the Web encourages and normalizes cruelty—that rage and abuse “is endemic on the Internet” (2011, p. 237). While it would be difficult to argue that cruelty among strangers is not common within digitally-mediated interactions, but the question this invites is whether this is the only thing going on.

Two years of participant observation in the sex camming and DIY porn communities suggest to me that it isn’t. I’ll share more of those findings in future posts.

PJ Patella-Rey (@pjrey) is an XBIZ nominated clip producer and a PhD candidate in sociology.

[updated 5/9/18. substantially revised based on further reading and reflection.]

I need to start this essay by making one thing clear: I will not in any way suggest that cam girls or the work that they do is problematic. On the contrary, this essay is aimed at appreciating some of the complexity involved in this form of sex work. In particular, it examines how the culturally ubiquitous trope of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl (MPDG) shapes the expectations an audience might place on cammers (especially young cis-women cammers) and how cammers anticipate and capitalize on such expectations.

I need to start this essay by making one thing clear: I will not in any way suggest that cam girls or the work that they do is problematic. On the contrary, this essay is aimed at appreciating some of the complexity involved in this form of sex work. In particular, it examines how the culturally ubiquitous trope of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl (MPDG) shapes the expectations an audience might place on cammers (especially young cis-women cammers) and how cammers anticipate and capitalize on such expectations.