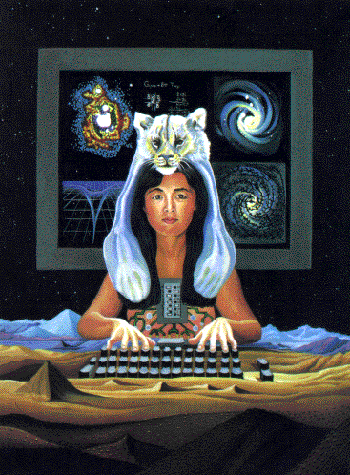

While we do not necessarily use the term “cyborg” in the way Donna Haraway used it in her famous 1985 “Cyborg Manifesto,” Haraway’s work is of great importance to many of the topics covered on the Cyborgology blog.

While we do not necessarily use the term “cyborg” in the way Donna Haraway used it in her famous 1985 “Cyborg Manifesto,” Haraway’s work is of great importance to many of the topics covered on the Cyborgology blog.

As I see it, the primary takeaway from Haraway is the existence of a recursive relationship between technology and social organization. More importantly, as each iteration of this relationship unfolds, there opens a new field across which power relations operate. Haraway is far more optimistic than Foucault or Baudrillard, however, who opine about our inability to escape the techno-social system. For Haraway, we become empowered by figuring out, and, subsequently learning to manipulate, the code that organizes society in any given technological milieu.

Like Foucault, however, Haraway is intensely focused the relation between discourse and power. In fact, she frequently cites the need for scholars and activists to engage in “category work.” Haraway assumes that social institutions pivot on systems of categorization – often to the detriment of persons who do not fit the primary categorizations. Category work is, first and foremost, a process blurring the boundaries between these primary categories, and, as such, creating new possibilities for being inside the system. Today, it is popular to describe this process as “queering” boundaries. It is also in this context that she claims, “[a]ll kinds of interesting stuff is going on under the prefixes post- and trans-.” The prefixes are simply used to signify counter-hegemonic discourses. Consider, for example, “post-humanism.” The mistake would be to interpret this term as an empirical statement that we are no longer human. Haraway would likely consider such a position “blissed-out technoidiocy.” Instead, post-humanism” is a claim that the category “human,” as we have constructed it, is no longer sufficient. Thus, implied in every “post-” and “trans-” is a semantic argument, but it is not merely a semantic argument since power and discourse are always intertwined.

Haraway has a nuanced vision of social change that is neither fully structural nor fully agentic. The very fact of technological development (arguably a structural necessity of capitalism) creates new interpretive opportunities, which individuals may seize upon to challenge prevailing norms. Breast augmentation, for example, might serve to support the dominant image of the female body. But, it might also challenge that same image by facilitating transgenderism. Thus, Haraway champions what I would call “co-optation” as a strategy of social change, whereby marginalized groups seize the tools of the dominant groups and use them for their own ends.

The following quote, I believe, captures the three themes (i.e., the recursivity between technology and social order; the material implications of category work; and co-optation):

[…] knowledge projects these days constitute their objects of attention in the Foucauldian sense – as discourse constitutes it own objects of attention. This is not a relativist position. This is not about things being merely constructed in a relative sense. This is about those objects that we non-optionally are. […] It is not that this is the only thing that we or anyone else is. It is not an exhaustive description but it is a non-optional constitution of objects, of knowledge in operation. It is not about having an implant, it is not about liking it. This is not some kind of blissed-out technobunny joy in information. It is a statement that we had better get it – this is a worlding operation. Never the only worlding operation going on, but one that we had better inhabit as more than a victim. We had better get it that domination is not the only thing going on here. We had better get it that this is a zone where we had better be the movers and the shakers, or we will be just victims.

Haraway is neither wholly positive or negative about the emergence of new technologies. Instead, technological development is both an opportunity and a danger, and as such, it as an imperative to act. Though, she also cautions us that more is going on in the world than what happens in the field of technology, so we must be wary of becoming too myopic.

While I have briefly sketched some themes in Haraway’s work as it pertains to technology, I have said little about the Feminist and socialist aspects of her work. I would be remiss to not, at least, point out that she sees all these aspects a fundamentally intertwined.