Earlier this week, I posted a remembrance of the ways Zygmunt Bauman influenced us here at Cyborgology. In this post, I reflect on–and attempt to further develop–some of the aspects of Bauman’s thought that may be useful to us as we continue our work theorizing digital media.

Two things I most admired about Zygmunt Bauman were his ability to relate his theories to current events (even as he aged into his 90s) and the way he always manage to connect social theory and moral philosophy–how to achieve justice as a society and lead a good life as an individual.

To the former point, Bauman was remarkably prolific up until his final days. In a 2016 interview that sets the tone for my reflection here, he argued:

most people use social media not to unite, not to open their horizons wider, but on the contrary, to cut themselves a comfort zone where the only sounds they hear are the echoes of their own voice, where the only things they see are the reflections of their own face. Social media are very useful, they provide pleasure, but they are a trap. You should only trust some authorized sites for checking reviews.

This notion of social media as a pleasurable trap–and how Bauman comes to understand it this way–is the lens through which I would like to review his sizable body of work.

Pleasurable Traps: Beyond the Panopticon

The final decade and a half of Bauman’s life was, almost obsessively, devoted to developing his concept of liquidity “as the leading metaphor for the present stage of the modern era” (Liquid Modernity, p. 2). Early modernity was largely concerned with the development of enduring structures that could control space for extended periods of time. Nation states and prisons exemplify how control was tied to spatial relations in early modernity. Late, “liquid” modernity, however, is distinguished by accelerated movement of both information and material objects. Rigid structures tied to particular spaces become less important than the movement of the flows that pass easily between them. Bauman explains (Liquid Modernity, pp. 10-11):

the long effort to accelerate the speed of movement has presently reached its ‘natural limit’. Power can move with the speed of the electronic signal – and so the time required for the movement of its essential ingredients has been reduced to instantaneity. For all practical purposes, power has become truly exterritorial, no longer bound, not even slowed down, by the resistance of space… It does not matter any more where the giver of the command is – the difference between ‘close by’ and ‘far away’… has been all but cancelled.

This being the case, Bauman argues that we need to move beyond the theoretic frameworks used to make sense of control in early modernity–most significantly, we need to move beyond the metaphor of the panopticon described by Michel Foucault in Discipline and Punish. The guards of liquid modernity can watch from anywhere and the prisoners can be watched anywhere. Bauman explains (Liquid Modernity, p. 10) that panoptic control is

burdened with… handicaps… It is an expensive strategy: conquering space and holding to it as well as keeping its residents in the surveilled place… [rapid movement] gives the power-holders a truly unprecedented opportunity: the awkward and irritating aspects of the panoptical technique of power may be disposed of. Whatever else the present stage in the history of modernity is, it is… above all, post-Panoptical.

Though not without its flaws, Bauman’s 2013 collaboration with David Lyon, titled Liquid Surveillance, most forcibly made the case that we need to move beyond the metaphor of the panopticon if we truly hope to understand how the relationship between visibility and control works in the age of social media. A decade earlier in Liquid Modernity, Bauman (drawing on Thomas Mathiesen), had already suggested we examine “synoptic” power structures, where the many now watch the few but the few still maintain influence over the many by producing spectacles for the many to consume. Liquid Surveillance pushes the conversation a step further, suggesting we consider “ban-optic” power structures (a term coined by Didier Bigo), which, unlike the panopticon, are not confined to a specific institution but are applied to society– and even the global population–as a whole. The fundamental mechanism behind ban-optic structures is social sorting by way of profiling and algorithmic prediction. The ban-opticon pressures us to conform to normalized patterns of behavior or else be categorized as a potential threat and, thus, subjected to greater surveillance and diminished rights. Perhaps even more concerning, ban-optic power structures often draw boundaries of exclusion based on involuntary categories such as race, citizenship, or genetic markers. These discussions of the ban-opticon now seems prescient as we transition toward a Trump presidency.

While these were important insights, I would argue that it is not what Bauman explicitly said here about surveillance that is most significant, but the discussions that his worked helped open the door to.

First, the conversation about surveillance and social media has finally moved past the metaphor of the panopticon. Excellent books like David Savat’s Uncoding the Digital [my review] are attempting to develop entirely new frameworks for understanding more fluid forms of surveillance. Bauman stretches the concept of the synopticon almost beyond recognizability to the point that his recent work all but begs for new conceptual tools. Further development of terms like “omniopticon” (used by Nathan Jurgenson and George Ritzer to describe many-many surveillance dynamics) are still sorely needed.

Second, we we have begun to see that the model of surveillance is no longer an iron cage but a velvet one–it is now sought as much as it is imposed. Social media users, for example, are drawn to sites because they offer a certain kind of social gratifaction that comes from being heard or known. Such voluntary and extensive visibility is the basis for a seismic shift in the way social control operates–from punitive measures to predictive ones. Bauman explains (Liquid Surveillance, pp. 65-66):

With the carrot (or its promise) replacing the stick, temptation and seduction taking over the functions once performed by normative regulation, and the grooming and honing of desires substituting for costly and dissent-generating policing… I would rather abstain from using the term ‘panopticon’ in this context. The professionals in question are anything but the old-fashioned surveillors watching over the monotony of the binding routine; they are rather trackers or stalkers of the exquisitely changeable patterns of desires and of the conduct inspired by those volatile desires.

The imposing nature of the panopticon is rapidly being designed out of surveillance technologies, and Silicon Valley’s goal of “frictionless” sharing on social media exemplifies this trend. Social control, itself, has become more adaptive and individualized–more fluid–and Bauman’s work gives us a language to talk about this.

Pleasurable traps depend on this sort of fluidity; they must adjust themselves to most efficiently channel the desires and behaviors of each individual. When effective, such traps are not experienced as an imposition but as opportunity. In his most hyperbolic moments, Bauman made statements such as:

we no longer employ technology to find the appropriate means for our ends, but we instead allow our ends to be determined by the available means of technology. We don’t develop technologies to do what we want to be done. We do what is made possible by technology.

If we take this too seriously, we might conclude that Bauman believed we have all become dupes. But, he, himself, gives us tools to understand why this is not so.

Bauman suggests that–following modernity’s failure to divide the world up into definite and enduring categories–ambiguity and ambivalence define post-modern logic. It is useful to think about pleasurable traps as being ambivalent to our ends/desires. Ambivalence is necessary to achieve flexibility. There is no singular, ideal way to be ensnared. Pleasurable traps modulate themselves to be the means to many different ends; they only encourage users to adapt when they reach the limits of their own adaptability. And, they only tend to bar entry when they exhaust efforts to co-adapt with the user.

Returning to the example of social media, platforms generally attempt to maximize their user base. They may encourage happy posts but will happily accept all your uncle’s political rants. They may encourage you, time and again, to fill out your “about me” information, but will let you get away with leaving most things blank. They may encourage you to friend or follow an ex, but will also allow you to perpetually ignore these suggestions. They may even tolerate some rule-breaking (e.g., Facebook’s real name policy) in order to keep users in the system. Generally speaking, the only things that can get you barred from a platform is if you either drive other users away or if you engage in sabotage.

Part I summary: As the paradigmatic example of a pleasurable trap–the form of social control native to liquid modernity–social media is highly flexible in adapting itself to individual users and is largely ambivalent to their desires.

Pleasurable Traps as Post-Modern Sorcery and Enchantment

Bauman’s discussions of liquidity and surveillance were not, themselves, the primary focus of his work, but rather pieces of a much larger legacy of theorizing social control–a legacy that begins with his defining work on Modernity and the Holocaust. Bauman did not view the Holocaust as an aberration in Western history or a setback in its progress; instead, he saw it as modernity’s logical conclusion. Bauman was deeply critical of modernity and its relentless pressure to rationalize and control the world; he likened it to a gardener who establishes order only by eliminating that which does not fit neatly into their prescribed categories. In Bauman’s words (Modernity and the Holocaust, p. 18):

the bureaucratic culture which prompts us to view society as an object of administration, as a collection of so many ‘problems’ to be solved, as ‘nature’ to be ‘controlled’, ‘mastered’ and ‘improved’ or ‘remade’, as a legitimate target for ‘social engineering’, and in general a garden to be designed and kept in the planned shape by force (the gardening posture divides vegetation into ‘cultured plants’ to be taken care of, and weeds to be exterminated), was the very atmosphere in which the idea of the Holocaust could be conceived, slowly yet consistently developed, and brought to its conclusion.

Bauman contrasts the early modern logic of control embodied by the gardener with the pre-modern figure of the gamekeeper–who assumes order to be intrinsic to the nature of things according to a divine plan–and with the post-modern figure of the hunter–who tries capture as many trophies as they can without concern for the nature of the landscape, the future existence of the game, or even other hunters. Bauman suggests we now live, predominantly, in a would of hyper-individualistic hunters (“Living in Utopia,” p. 5):

we would need to try really hard to spot a gardener who contemplates a predesigned harmony beyond the fence of his private garden and then goes out to bring it about. We certainly won’t find many gamekeepers with similarly vast interests… That increasingly salient absence is called ‘deregulation’.

Returning now to the idea of a pleasurable trap, Bauman unwittingly seems to be pushing us beyond the metaphor of a hunter who cares nothing for the landscape. Liquid modernity, as exemplified by social media, does, in fact, feature figures who are deeply concerned with the landscape: these the are the engineers behind all the platforms and algorithms that allow pleasurable traps to modulate themselves to the desires of each user.

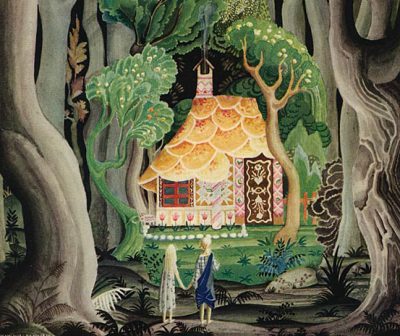

Extending Bauman’s metaphors, I suggest we add the figure of the sorcerer, who conjures up an illusory landscape tailored to the desires of each passerby. The sorcerer’s conjured landscape is fluid but ensnares that which flows through it (at least temporarily). The sorcerer also uses their power to banish enemies. The magic of the conjured landscape is that it not only lures desirable victims in, but also that acts as a barrier keeping undesirable victims out. The sorcerer does not replace the hunter; rather, sorcerer hunts the hunter, preying on their individual desires–each conjured landscape filled with attractive game likely to lure the hunter in.

The pleasurable trap is a conjured landscape–a creation of the sorcerer, a site of enchantment. Interestingly, enchantment is another concept Bauman uses to describe post-modernity (Intimations of Postmodernity, p. x) :

postmodernity can be seen as restoring to the world what modernity, presumptuously, had taken away; as a re-enchantment of… the world that modernity tried hard to dis-enchant

Bauman further explains that, in a re-enechanted world, “the mistrust of human spontaneity, of drives, impulses and inclinations resistant to prediction and rational justification, has all but been replaced by the mistrust of the unemotional, calculating reason” (Postmodern Ethics, p. 33). Using this langauge, we can say that pleasurable traps are pleasurable because they have been re-enchantmented–they allow for individual expression and meaning-making, unlike previous apparatuses of control.

But, the “re-” in “re-enchantment” is key, here, and Bauman seems to forget that at times. Enchantment cannot return us to a pre-modern state. Contrary to Bauman’s previous quote, predictibility–and rationalization, for that matter–still remain key aspects of post-modernity; they have just imploded with–or, perhaps, been concealed by–less rational, less modern ways of being. Expanding on Bauman, George Ritzer (Enchanting a Disenchanted World, p. 70) observes that “efforts at reenchantment may, themselves, be rationalized from the very beginning”; he (ibid, p. 7) describes these re-enchanted systems as “‘cathedrals of consumption’–that is, they are structured, often successfully, to have an enchanted, sometimes even sacred, religious character… to offer, or at least appear to offer increasingly magical, fantastic, and enchanted settings in which to consume.” Whether we call them “conjured landscapes,” “cathedrals of consumptions,” or “pleasurable traps,” these concepts all point our attention toward rationalized structures that have been re-enchanted.

Of particular relevance to our main case of interest–i.e., social media–Ritzer notes that “rather than having their consumption orchestrated by people like advertising executives and directors of cathedrals of consumption, it may be that it is consumers who are in control” (Enchanting a Disenchanted World, p. 75). That is not to say that users/consumers/hunters are in absolute control; but, their desires do determine the shape that these conjured landscapes take and their willingness to continually pass through such pleasurable traps incentivizes sorcerers to continue to conjurer them.

In this way, pleasurable traps implode rationality and irrationality, freedom and control. This implosion–the capacity to embody contradiction–is the true magic–the spell post-modernity hath cast.

Part II summary: Though they are still rational at their core, what differentiates pleasurable traps (such as social media) from early modern forms of social control (such as the panopticon) is that they have been re-enchanted; individual freedom for expression and meaning-making are now essential to their functioning. To Bauman’s list of metaphorical figures (i.e., the gamekeeper, gardener, and hunter), we can add the sorcerer, who represents the powers that conjure these re-enchanted apparatuses into being.