Julian Assange, the notorious founder and director of WikiLeaks, is many things to many people: hero, terrorist, figurehead, megalomaniac. What is it about Assange that makes him both so resonant and so divisive in our culture? What, exactly, does Assange stand for? In this post, I explore two possible frameworks for understanding Assange and, more broadly, the WikiLeaks agenda. These frameworks are: cyber-libertarianism and cyber-anarchism.

First, of course, we have to define these two terms. Cyber-libertarianism is a well-established political ideology that has its roots equally in the Internet’s early hacker culture and in American libertarianism. From hacker culture, it inherited a general antagonism to any form of regulation, censorship, or other barrier that might stand in the way of “free” (i.e., unhindered) access of the World Wide Web. From American libertarianism it inherited a general belief that voluntary associations are more effective in promoting freedom than government (the US Libertarian Party‘s motto is “maximum freedom, minimum government”). American libertarianism is distinct from other incarnations of libertarianism in that tends to celebrate the market and private business over co-opts or other modes of collective organization. In this sense, American libertarianism is deeply pro-capitalist. Thus, when we hear the slogan “information wants to be” that is widely associated with cyber-libertarianism, we should not read it as meaning gratis (i.e., zero price); rather, we should read it as meaning libre (without obstacles or restrictions). This is important because the latter interpretation is compatible with free market economics, unlike the former.

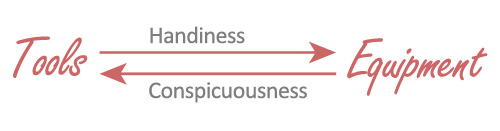

Cyber-anarchism is a far less widely used term. In practice, commentators often fail to distinguish between cyber-anarchism and cyber-libertarianism. However, there are subtle distinctions between the two. Anarchism aims at the abolition of hierarchy. Like libertarians, anarchists have a strong skepticism of government, particularly government’s exclusive claim to use force against other actors. Yet, while libertarians tend to focus on the market as a mechanism for rewarding individual achievement, anarchists tend to see it as means for perpetuating inequality. Thus, cyber-anarchists tend to be as much against private consolidation of Internet infrastructure as they are against government interference. While cyber-libertarians have, historically, viewed the Internet as an unregulated space where good ideas and the most clever entrepreneurs are free to rise to the top, cyber-anarchists see the Internet as a means of working around and, ultimately, tearing down old hierarchies. Thus, what differentiates cyber-anarchist from cyber-libertarians, then, is that cyber-libertarians embrace fluid, meritocratic hierarchies (which are believed to be best served by markets), while anarchists are distrustful of all hierarchies. This would explain while libertarians tend to organize into conventional political parties, while the notion of an anarchist party seems almost oxymoronic. Another way to understand this difference is in how each group defines freedom: Freedom for libertarians is freedom to individually prosper, while freedom for anarchists is freedom from systemic inequalities.

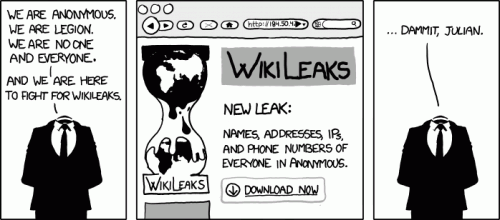

In many ways, the Internet community / hacker collective known as “Anonymous” are the archetypical cyber-anarchist group. As their namesake indicates, they embrace a principle of anonymity that places inherent limits on hierarchy within the group. Members often work collectively to disrupt the technology infrastructure of established institutions (often in response to perceived abuses of power). All actions initiated by the group are voluntary and it is said that anyone can spontaneously suggest a target. The ethos of the organization was well-captured in a quote from one of its Twitter feeds: “RT: @Asher_Wolf: @AnonymousIRC shouldn’t be about personalities. The focus should always be transparency for the powerful, privacy for the rest.” [Author’s Note: The previous sentence was ambiguously phrased. @Asher_Wolf is not personally affiliated with Anonymous. I meant merely to suggest that her comment was insightful. My apologies to her if readers were misled.] Note that this implicit linkage between transparency and accountability is what distinguishes a cyber-anarchist from other run-of-the-mill anarchists. For the cyber-anarchist, the struggle against power is a struggle for information.

In many ways, the Internet community / hacker collective known as “Anonymous” are the archetypical cyber-anarchist group. As their namesake indicates, they embrace a principle of anonymity that places inherent limits on hierarchy within the group. Members often work collectively to disrupt the technology infrastructure of established institutions (often in response to perceived abuses of power). All actions initiated by the group are voluntary and it is said that anyone can spontaneously suggest a target. The ethos of the organization was well-captured in a quote from one of its Twitter feeds: “RT: @Asher_Wolf: @AnonymousIRC shouldn’t be about personalities. The focus should always be transparency for the powerful, privacy for the rest.” [Author’s Note: The previous sentence was ambiguously phrased. @Asher_Wolf is not personally affiliated with Anonymous. I meant merely to suggest that her comment was insightful. My apologies to her if readers were misled.] Note that this implicit linkage between transparency and accountability is what distinguishes a cyber-anarchist from other run-of-the-mill anarchists. For the cyber-anarchist, the struggle against power is a struggle for information.

So, is Julian Assange a cyber-libertarian or a cyber-anarchist? This proves difficult to sort out. Assange is an activist, not a philosopher, so we ought not to expect his theoretical statements to be completely coherent; nevertheless, he does appear to be operating with a consistent and quite nuanced philosophy. A recent Forbes interview is revealing. Though, Assange is quite evasive in his own ideological self-identification:

It’s not correct to put me in any one philosophical or economic camp, because I’ve learned from many. But one is American libertarianism, market libertarianism.

So, Assange is relatively clear in is his affinity for both markets and libertarianism. In fact, Assange justifies Wikileaks’ activities, in part, through pro-market rhetoric, saying, for example, that:

WikiLeaks means it’s easier to run a good business and harder to run a bad business, and all CEOs should be encouraged by this. […] it is both good for the whole industry to have those leaks and it’s especially good for the good players. […] You end up with a situation where honest companies producing quality products are more competitive than dishonest companies producing bad products.

Yet, WikiLeaks frequently engages in what might be interpreted in as anti-business activity—distributing proprietary information (e.g., documents that indicate insider trading at JP Morgan, a list of companies indebted to Iceland’s failing Kaupthing Bank, legal documents showing that Barclays Bank sought a gag order against the Guardian, a list of accounts concealed in the Cayman Islands, etc.). In fact, Assange claims that 50% of the data in their repository is related to the private sector.

Why would Assange threaten these businesses if he is so pro-market? Assange offers a clue when he says, “I have mixed attitudes towards capitalism, but I love markets.” The two parts of this statement are reconcilable because capitalism is primary about private ownership of the means of productions, while markets are primarily about the decentralization of supply and demand. Historically speaking, markets certainly preceded capitalism. He believes Wikileaks assists markets in the following way:

To put it simply, in order for there to be a market, there has to be information. A perfect market requires perfect information.

In any case, Assange seems to be saying that he favors minimal interference in the relationship between supply and demand, but he is skeptical as to whether private ownership of the means of product (as opposed to collectivist or government control) is the best means of accomplishing this goal. He explains the thinking behind this nuanced position of supporting markets, while being skeptical towards capitalism:

So as far as markets are concerned I’m a libertarian, but I have enough expertise in politics and history to understand that a free market ends up as monopoly unless you force them to be free.

The next question is, naturally: Who should be responsible for forcing markets to be free? Given his generally negative assessment of governments, it is unsurprising when Assange balks at the notion the governments are up to the task. Assange seems to favor the promotion of culture of transparency as a substitute for regulations. He explains:

I’m not a big fan of regulation: anyone who likes freedom of the press can’t be. But there are some abuses that should be regulated […].

Traditionally, regulations are controls placed on one set of institution (i.e., businesses) by another institution (i.e., government). Here, I think, is where Assange’s fundamental thinking is revealed. He does not trust institutions to regulate each other, because he does not trust institutions. He seems to believe that institutions, and their propensity for secrecy, have a corrupting effect. This is why he champions individuals and small groups—extra-institutional actors—as change agents. Anti-institutionalism appears to be Assange’s driving principle—even more so than his appreciation for markets. This, paired with his skepticism toward capitalism, seems to indicate that Assange better fits the ideal-type of the cyber-anarchist than that of the cyber-libertarian. The arc of Assange’s argument is not so much that the public sector’s role in decision-making should be minimized in favor of private entrepreneurs, rather he seems to believe that—insofar as it is possible without descending into complete chaos—institutions should be diminished in favor of extra-institutional actors (i.e., individuals and small voluntary associations). Wikileaks is attempt, on the part of extra-institution, to exercise more accountability over institutions through the mechanism of transparency.

It should be noted that Assange has resisted attempts to label him as “anti-institutional,”explaining that he has visited countries where institutions are non-functional and that this sort of chaos is not what he has in mind. One, thus, has to infer that Assange believes institutions are a necessary evil—one that must be guarded against through enforced transparency. In the classic sociological framework, we might position Assange as a sort of conflict theorist: People require institutions for order and stability, yet are perpetually threatened by the tyrannical inclinations of such institutions; he believes the people can only gain the upper hand in the struggle by preventing/exposing institutional secrets.

From the previous statements, we can conclude that Assange has two central assumptions about our social world: 1.) Institutions, by their nature, will always become corrupt when not closely monitored. 2.) Secrecy is a necessary precondition for corruption; diminish secrecy and you diminish corruption. To take a bit of a critical angle, it appears that the degree of faith in transparency expressed by Assange and his compatriots seems to necessitate either a lack of attentiveness to power and/or a sort of naïve optimism that deeply embedded power relations can be easily overturned. Does simply knowing that an institution is corrupt really sufficiently empower us to end that corruption? The lack of prosecutions in light of the all the malfeasance and outright criminality that led to the recent collapse of the financial sector would seem to indicate otherwise. As Michel Foucault and countless other theorists have argued, there is a definite relationship between visibility and power; however, it may not be as direct or as simplistic as Assange appears to believe. To be fair to Assange, he is not necessarily arguing that, through transparency, individuals are empowered to hold institutions accountable but, instead, that information can be used strategically to play institutions against one another.

From the previous statements, we can conclude that Assange has two central assumptions about our social world: 1.) Institutions, by their nature, will always become corrupt when not closely monitored. 2.) Secrecy is a necessary precondition for corruption; diminish secrecy and you diminish corruption. To take a bit of a critical angle, it appears that the degree of faith in transparency expressed by Assange and his compatriots seems to necessitate either a lack of attentiveness to power and/or a sort of naïve optimism that deeply embedded power relations can be easily overturned. Does simply knowing that an institution is corrupt really sufficiently empower us to end that corruption? The lack of prosecutions in light of the all the malfeasance and outright criminality that led to the recent collapse of the financial sector would seem to indicate otherwise. As Michel Foucault and countless other theorists have argued, there is a definite relationship between visibility and power; however, it may not be as direct or as simplistic as Assange appears to believe. To be fair to Assange, he is not necessarily arguing that, through transparency, individuals are empowered to hold institutions accountable but, instead, that information can be used strategically to play institutions against one another.

In this way, Assange is more nuanced than he often appears in media caricatures. WikiLeaks is not, simply, an effort at maximal transparency; rather, it is involved in a complex game of reveal and conceal, motivating institutions oppose or compete with one another. In fact, in a separate interview, Assange even praises secrecy, saying that:

secrecy is important for many things but shouldn’t be used to cover up abuses, which leads us to the question of who decides and who is responsible. It shouldn’t really be that people are thinking about, Should something be secret? I would rather it be thought, Who has a responsibility to keep certain things secret? And, who has a responsibility to bring matters to the public? And those responsibilities fall on different players. And it is our responsibility to bring matters to the public.

At his most cynical and, perhaps, megalomaniacal, Assange sounds as if the only person that can be trusted to regulate governments and businesses is Julian Assange. More generously, we can interpret that Assange’s rhetoric and WikiLeak’s actions indicate a general antagonism to institutions that places them much closer to the cyber-anarchists of Anonymous than the cyber-libertarians barons of Silicon Valley (e.g., Mark Zuckerberg, Eric Schmidt) who support enforced transparency, primarily, for their own financial gain.

Follow PJ Rey on Twitter: @pjrey