I’m posting to get some feedback on my initial thoughts in preparation for my chapter in a forthcoming gamification reader. I’d appreciated your thoughts and comments here or @pjrey.

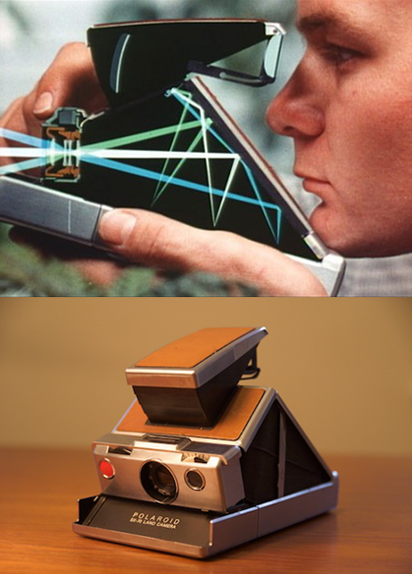

![]() My former prof Patricia Hill Collins taught me to begin inquiry into any new phenomenon with a simple question: Who benefits? And this, I am suggesting, is the approach we must take to the Silicon Valley buzzword du jure: “gamification.” Why does this idea now command so much attention that we feel compelled to write a book on it? Does a typical person really find aspects of his or her life becoming more gamelike? And, who is promoting all this talk of gamification, anyway?

My former prof Patricia Hill Collins taught me to begin inquiry into any new phenomenon with a simple question: Who benefits? And this, I am suggesting, is the approach we must take to the Silicon Valley buzzword du jure: “gamification.” Why does this idea now command so much attention that we feel compelled to write a book on it? Does a typical person really find aspects of his or her life becoming more gamelike? And, who is promoting all this talk of gamification, anyway?

It’s telling that conferences like “For the Win: Serious Gamification” or “The Gamification of Everything – convergence conversation” are taking place in business (and not, say, sociology) departments or being run by CEOs and investment consultants. The Gamification Summit invites attendees to “tap into the latest and hottest business trend.” Searching Forbes turns up far more articles (156) discussing gamification than the New York Times (34) or even Wired (45). All this makes TIME contributor Gary Belsky seems a bit behind the time when he predicts “gamification with soon rule the business world.” In short, gamification is promoted and championed—not by game designers, those interested in game studies, sociologists of labor/play, or even computer-human interaction researchers—but by business folks. And, given that the market for videogames is already worth greater than $25 billion, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that business folk are looking for new growth areas in gaming.

Thus, Ian Bogost appears to be on the mark when he declares that gamification is nothing more than “marketing bullshit,” suggesting “‘exploitationware’ as a more accurate name for gamification’s true purpose.” (Bogost has a way with words that eludes the Marxist thinkers that generally tackle the concept of exploitation.) In one piece, he argues (interestingly, his audience is a business crowd) that gamification is about replacing real incentives for customer loyalty with “counterfeit incentives that neither provide value nor require investment.” That is to say, “points” or whatever other incentive consumers can earn in the game are not translatable into real world benefits. He concludes that this amounts to a sham, because consumers are being offered something that is really nothing.

I generally agree with Bogost’s argument here, but I think his is only a partial critique. Bogost focuses exclusively on how gamification relates to consumption, but I believe gamification has more to do with production. More to the point, I want to argue that gamification is primarily about companies duping people into doing free labor. Before I proceed with contextualizing and supporting this claim, I want to acknowledge upfront that gamification is a means not and ends. As danah boyd (in recent Pew report) observed, gamification is

a modern-day form of manipulation. And like all cognitive manipulation, it can help people and it can hurt people. And we will see both.

In fact, there have been many attempts to put gamification to use in the pursuit of goals other than profit (see, for example, Foldit and Leafsnap). Molleindustria (which achieved recent fame for it’s Phone Story game) has, arguably, gamified politics in a radically subversive way. However, gamification’s supposed profit potential is the overwhelming reason for its hype.

Gamification and the Production of Playbor

Gamification, broadly defined, is the introduction of play elements into other kinds of activity. However, this definitions gets muddied pretty quickly once we acknowledge that there is no consensus as to how we should define play. Rather than getting bogged down in a debate about the nature of play, I will simply borrow from Johan Huizinga‘s Homo Ludens (1938), which is the most widely-cited work on the concept of play, and perhaps, the first to offer a precise, if rather complex, definition of play. For our purposes, the most import aspect of Huizinga’s definition is that it is separate from material gain or profit—in short, (capitalist) production. (I do not claim that this is the “correct” definition of play (perhaps play is a concept that resist definition), just that it is useful in making my argument about gamification.)

I have previously argued that play and labor were, traditionally, defined in a way that makes them mutually exclusive. Marx (focusing here on Capital and not the earlier manuscripts) defined labor as value-producing activity and articulated an equivalence between the two in his labor theory of value, saying “the measure of the expenditure of labour power by the duration of that expenditure, takes the form of the quantity of value of the products of labour.” Opinions and interpretations of Marx aside, the notion of labor as being value-producing activity is firmly embedded in Western intellectual landscape.

Between Marx and Huizinga, our Modernist heritage is an understanding that labor is activity that creates value and play is activity that never creates value—and never the two shall meet. Of course, there is no reason to uncritically accept this quasi-binary.

(to watch Julian Kücklich discuss “playbour,” start at 1:03:41)

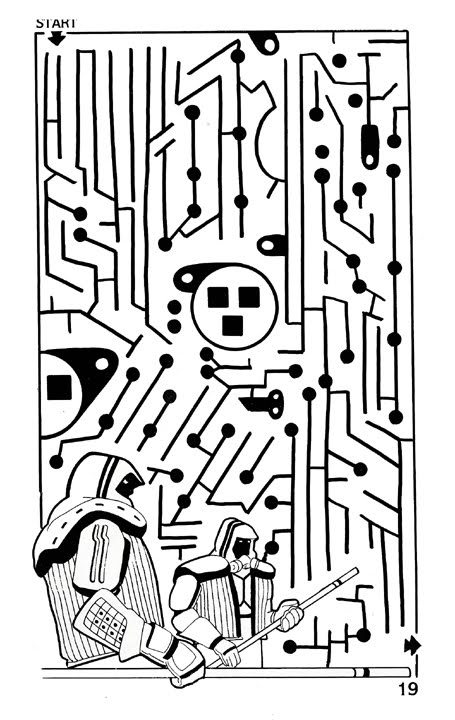

Critical inquiry into the (illusory) boundary between labor and play leads us directly into the realm of playbor—one of the most significant and yet woefully under-theorized concepts put forth in the past decade. Julian Kücklich was the first academic to publish an article using the term and is certainly among the most cited commentator on the topic of playbor. Kücklich presents videogame “modding” as the paradigmatic example of how play and labor are imploded in a way that generally rewarding to capitalists, who retain property right to all modifications that users make to games and thus the exclusive right to profit off of them (of course, modders accumulate a certain amount of cultural capital in the process).

I find this example of modding relatively unsatisfying because, in this case, it doesn’t seem that we’re using the concept of playbor to talk about anything new. I suppose, modding is playbor in the sense that someone must set up a hoop and inflate a ball before a basketball game can commence. Sure, in this case, play presupposes a certain degree of work, and it is not insignificant that the players also do some of the work necessary to make play happen. But, in these examples, play and labor remain relatively distinct activities that happen to have a degree of mutually dependency. Mutually dependency, however, is a far cry from the indistinguishability that playbor seems to imply. Marx himself recognized that work and play were mutually dependent. Work provides the basic economics resources necessary for play, while play restores that productive energies that are sapped each day in the workplace. If playbor is nothing more than mutual dependency, then it is a deep-rooted and long-recognized part facet of capitalist production. However, I don’t think we’re attracted to the concept of playbor through observations of mutual dependency between work and play. Instead, I want to argue that playbor, in its ideal-typical form, would implode work and play into the very same act.

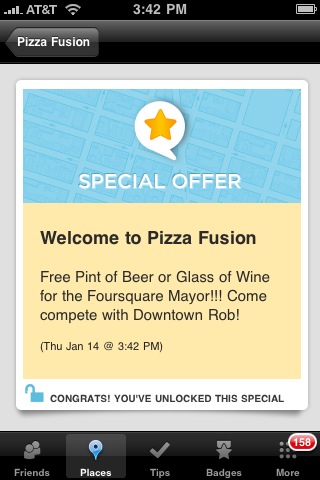

This brings us back, full circle, to gamification. If gamification is about inserting elements of games or play into other processes, then it would seem that gamification is a process of producing playbor; it is about converting ordinary work into playbor. Of course, gamification cannot be reduced to the production of playbor because it can be applied to processes other than labor—most notably, social interaction. Many institutions, for example, use “icebreakers” to organize and direct socializing by transforming it into a game. Foursquare might be the quintessential example of gamification, because it simultaneously makes both social and interaction and the work of recording data about one’s own movements into a game. Nevertheless, I do not think it unreasonable to say that our infatuation with gamification stems, primarily, from its capacity to produce playbor. Thus, the initial question I posed about who benefits is equally a question about who benefits from playbor.

It is clear that the business “gurus” who are driving the discourse on gamification, are primarily concerned with gamification as a mechanism for the production of new forms of value. At best, social interaction is a secondary concern that matters only insofar as it too facilitates further value creation. As we all well know, the ultimate goal of capitalism and the purpose of any mechanism it employs is the accumulation of wealth. Gamification cannot be understood apart from the mode of capitalist production and all the power relations and inequalities that implies. Like tools, tactics/techniques are never neutral. Thus, we must define gamification here in terms of its de facto function of producing (surplus) value and not just through its formal characteristic of introducing play into other activities. That is to say, we must consider not only what gamification does, but how and why it does.

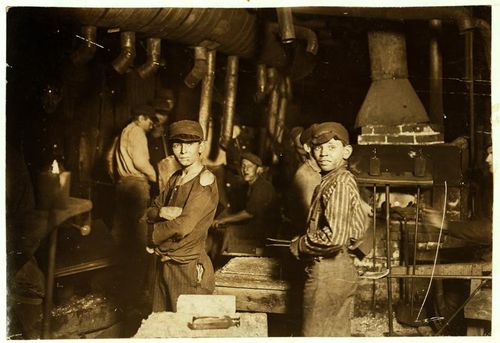

Turning to these latter questions now, I want to suggest that gamification is effective because it is a mechanism for de-coupling alienation from capitalist production. This is, actually, a rather extraordinary feat. Marx and generations of his intellectual successors viewed the factory as the archetype of capitalist production and, as such, have assumed that people only do such work because their economic conditions make it necessary for survival. It is nearly impossible to imagine a factory that is not alienating (at least, prior to robotics). Marx observed of the factory: “Its alien character emerges clearly in the fact that as soon as no physical or other compulsion exists, labor is shunned like the plague.” Importantly, workers’ have always reacted more strongly capitalism’s alienating character than to its exploitative character—no surprise, considering that the latter is often so well-concealed.

Yet, the contemporary realities of capitalism have shattered the assumption alienation is a necessary accompaniment to capitalist production, and nowhere is this more evident than in playbor. Playbor makes productive activity an end in-itself (namely, fun). Far from being shunned, playbor is sought out and done voluntarily. The object of production is no longer to create value; instead, value becomes a mere byproduct of play. Because playborers are not motivated by the value creation, they are apt to simply ignore it, leaving the capitalist to swoop in and take possession of as much of this surplus value as possible.

How is this bad? Playborer are having fun, so what’s the problem? Here, I must invoke Marx’s observation that “surplus value … for the capitalist, has all the charms of a creation out of nothing.” For the capitalist, the productive aspects of play are just latent value waiting to be “leveraged.” But this leveraging of surplus value is the precise moment that exploitation occurs.

The term “exploitation” is generally employed very loosely. In common parlance, “exploitation” means simply to use or to take advantage of someone. In (post-)Marxian labor analysis, however, exploitation has very specific meaning. Before we dive, momentarily, into the swamp of Marxian technical language, it’s important to make to aspects of exploitation clear upfront: 1.) In a Marxian context, exploitation meant only to describe relationship of exchange, and 2.) exploitation is a structurally necessary part of capitalism; it is the mechanism by which the capitalist comes to accumulate a disproportionately large share of the wealth.

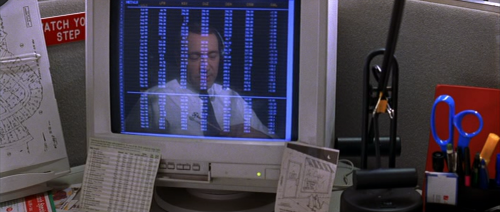

Marx observes that a typical worker’s wages is equivalent to only a fraction of the total value of what the worker produces. As such, only a fraction of the worker’s day is spent producing value for himself or herself. The rest of the day is spent producing “surplus” value that goes directly into the capitalist’s pocket. Exploitation is a ratio between how much of his or her own work returned in the form of wages and how much is kept as “surplus” by the capitalist. This is how we should interpret Marx when he concludes: “The rate of surplus value is… an exact expression for the degree of exploitation of labour-power by capital, or of the labourer by the capitalist.” Thus, as compensation approaches nothing, the rate of exploitation would seem to approach infinity; however such claims are probably a bit hyperbolic.

It’s too simple to say that playborers are uncompensated. The experience of play, of course, has intrinsic value. Moreover, playborers often accumulate some sort of symbolic capital. Pew researchers recently noted that these “rewards” can take a variety of forms, including “virtual… points, payments, badges, discounts, and “free” gifts; and status indicators such as friend counts, retweets, leader boards, achievement data, progress bars, and the ability to ‘level up.’” Symbolic capital accumulated through playbor may translate into monetary or cultural capital. In fact, this has always been true of play. For example, having a “grandmaster” chess ranking (which is calculated using a sophisticated point system) almost guarantees a player a certain degree of fame and material comfort. However, none of this negates the fact that playbor is exploitative. Like the paradigmatic factory workers, playborers only come to possess a small fraction of the value they create. Often, playborers obtain none of the monetary value they have created. And, of course, this is exactly how the playbor’s capitalist promoters want it.

Perhaps an even more insidious aspect of gamification is that it has the potential to expand capitalist production into new contexts. By masking work as play, capitalist production moves exploitation out of the work places and infiltrates our leisure time. Play loses its innocence. It is no longer an escape from the system, it is just another branch of it—a thing to be administered and controlled like everything else. Herbert Marcuse predicted and warned against this appropriation of play a half-century ago. Like Huizinga, Marcuse viewed play as a space apart from our workaday reality, and it that way, it had a certain liberatory—even revolutionary—potential. Marcuse explained “the play impulse does not aim at playing ‘with’ something; rather it is the play of life itself, beyond want and external compulsion—the manifestation of an existence without fear and anxiety, and thus the manifestation of freedom itself.” However, this is precisely because Marcuse subscribed to the Modernist assumption that work and play are distinction by their very nature.

For Marcuse, play is freedom because the system of capitalist production simply writes it off as useless—as something that cannot be put in use toward the ends of profit-making. He explains, “play is unproductive and useless because it cancels the repressive and exploitive traits of labor and [administered] leisure; it “just plays” with reality.” Thus, Marcuse, see capitalism as antagonistic to play. (Many businesses support this assumption by labeling as “time theft” any sort of play on the job.) In order to increase productivity, capitalists will attempt to eliminate play and divert that time and energy elsewhere.

Contrary to Marcuse’s assertions, playbor demonstrates that capitalism is capable of having a more sophisticated approach to play than simply re-directing it (or subjecting it to what Freudian thinkers might call “forced sublimation”). Playbor (and the process of gamification that produce it) demonstrate that capitalism can appropriate play into the process of production.

As I mentioned above, one reason that thinkers from Marx to Macuse argued that play persisted in capitalist economies is because it refreshed workers and restored their capacity to work effectively. In this sense, play was tolerated as necessary waste—time that was necessarily non-productive. The seduction of playbor is that it promises to make use of this necessary waste. It recycles that waste back into the structures of capitalist production. Waste is no longer wasted. Playbor is part of capitalism’s effort to colonize ever last moment in the waking day. (Perhaps, one day, we’ll figure out how to make sleep productive as well… dare I say it… sleepbor[TM]).

The introduction of play into labor only really gets at one aspect of playbor. Gamification still implies a certain sort of displacement: non-productive play activities are to be supplanted by productive play activities. But, there is an alternative means of creating playbor: We can find ways to make traditional, non-productive play activities productive. In contrast to gamification, we might use the term “workification” to describe this introduction of work elements (chiefly, productivity) into play (or other activities). So for example, Words with Friends and the official Scrabble app have turned a traditional game into a new way of collecting valuable data about people. Facebook has workified social interaction in the same way.

Caveats, Equivocations, etc.

Gamification is just another installment in a long history of ideological constructs put forth by capitalists to advance their agenda of further wealth accumulation. The discourse around gamification has overwhelming positive and almost universally uncritical. A few positive achievements (e.g., when Foldit players helped deduce the structure of the an enzyme used by the AIDS virus to reproduce) brought about through gamification have been used to mask the nefarious intent of those who promote gamification most vehemently: namely, to dupe us all into making even more money for them. This piece aims at producing what Judith Butler called “theoretical hyperboles… meant to advance a strategically aggressive counter-reading.” My hope is to change the conversation so that it is no longer acceptable for tech and business commentators to uncritically sing the praises of gamification.

Even for those who promote gamification for purposes other than self-enrichment, it is still important to adopt a critical perspective that looks for exploitation in all exchange relationships. The popularity of Amazon’s Mechanical Turk in recruiting “volunteers” for university research is a perfect example of how exploitation thrives when fields lack critical inquiry.

Finally, the focus of this piece has been on how play is being made productive. Implicit in this essay is the notion that the gamification (and playbor) are phenomena that have gained increased salience because of the Web. While I believe that gamification is one of many important trends that have emerged in light of the Web (else I wouldn’t be writing about it), I think that, thus far, it has received attention that is disproportionate to its significance. Far more important, is the trend of making social interaction productive (call it “weisure” or whatever you like). Productive social interaction is the bread and butter of every social networking site and, I think, is primary mechanism through which the Web is transformed into an engine of exploitation.