In 1967 (seven months before his assassination) Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. gave a speech to the American Psychological Association at their annual conference. According to APA, the text of his speech was reprinted in the Journal of Social Issues (Vol. 24, No. 1, 1968). While the speech was in galley proofs, the shocking and numbing news of his assassination was released.

The text of Dr. Martin Luther King’s speech (see in full below) is unfortunately still all too relevant, even 50 years later. Quotes that caught my attention in particular include, “White America needs to understand that it is poisoned to its soul by racism and the understanding needs to be carefully documented and consequently more difficult to reject. … All too many white Americans are horrified not with conditions of Negro life but with the product of these conditions-the Negro himself.”* Too much of US society continues to see the social, political and economic disadvantages of blacks as their own fault rather than the result of systematic and structural racism. Of late, ‘blaming the victim’ emerged in the police killings of Eric Garner and Michael Brown among many others (see my previous post: RACISM AND THE POLICE: The Shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson). A piece in the BBC by Stacey Patton and David Leonard points out this errant logic when applied to historical and more recent cases of black victims of police or vigilante violence:

- Emmett Till should not have whistled at a white woman.

- Amadou Diallo should not have reached for his wallet.

- Trayvon Martin should not have been wearing a hoodie.

- Jonathan Ferrell should not have run toward the police after getting into a car accident.

- Renisha McBride should not have been drinking or knocked on a stranger’s door for help in the middle of the night.

- Jordan Davis should not have been playing loud rap music.

- Michael Brown should not have stolen cigarillos or allegedly assaulted a cop.

Later in his speech, Dr. Martin Luther King states, “Negroes want the social scientist to address the white community and ‘tell it like it is.’ White America has an appalling lack of knowledge concerning the reality of Negro life.” Today, are we collectively doing enough to “tell it like it is”? Are we speaking to a wide enough audience? Do our students and the public that we engage still lack knowledge of the reality of persistent racial difference? Certainly. Should any student be able to graduate from college (or high school for that matter) without a thorough education of our society’s systems of race, gender, class, and sexuality? As academics we all have our areas of specialization, my doctoral training is not in race and ethnicity, but we can certainly find ways to address race and “tell it like it is” in at least one course we teach each semester.

Later in his speech, Dr. Martin Luther King states, “Negroes want the social scientist to address the white community and ‘tell it like it is.’ White America has an appalling lack of knowledge concerning the reality of Negro life.” Today, are we collectively doing enough to “tell it like it is”? Are we speaking to a wide enough audience? Do our students and the public that we engage still lack knowledge of the reality of persistent racial difference? Certainly. Should any student be able to graduate from college (or high school for that matter) without a thorough education of our society’s systems of race, gender, class, and sexuality? As academics we all have our areas of specialization, my doctoral training is not in race and ethnicity, but we can certainly find ways to address race and “tell it like it is” in at least one course we teach each semester.

Dr. Kings continues… “The decade of 1955 to 1965, with its constructive elements, misled us. Everyone, activists and social scientists, underestimated the amount of violence and rage Negroes were suppressing and the amount of bigotry the white majority was disguising.” Maybe not among social scientists, but the media and most politicians seemed complacent and strong in their belief that our society was “post-racial”. The protests in Ferguson and subsequently across the nation seemed to catch many off guard wondering why the black community was so angry.

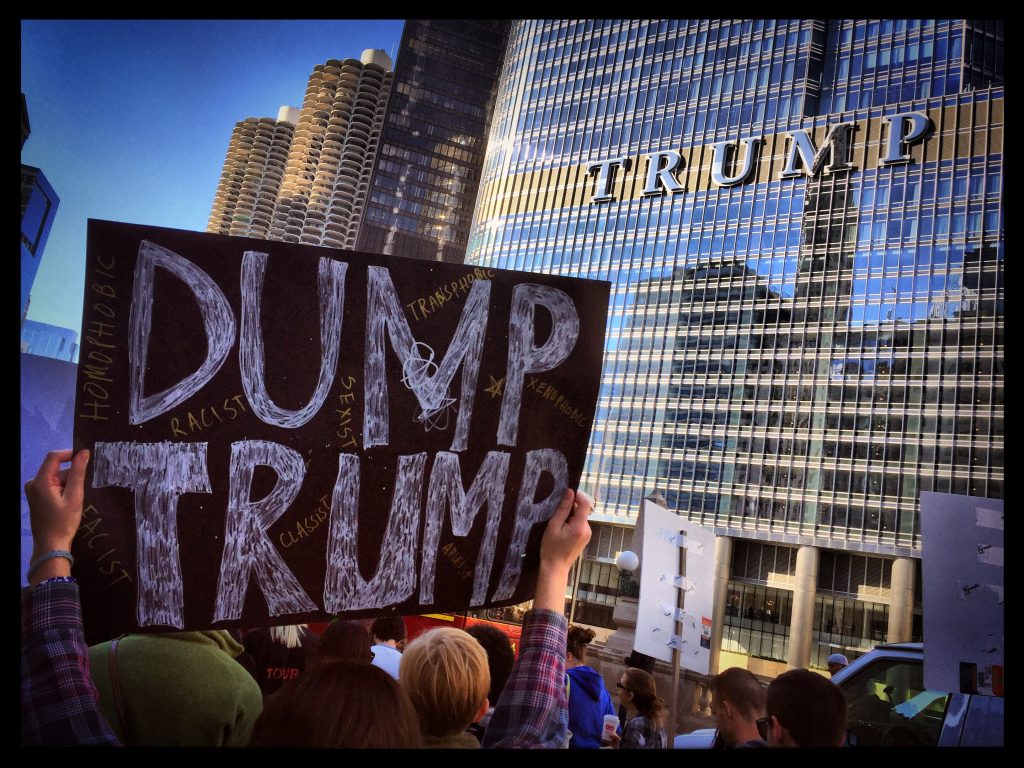

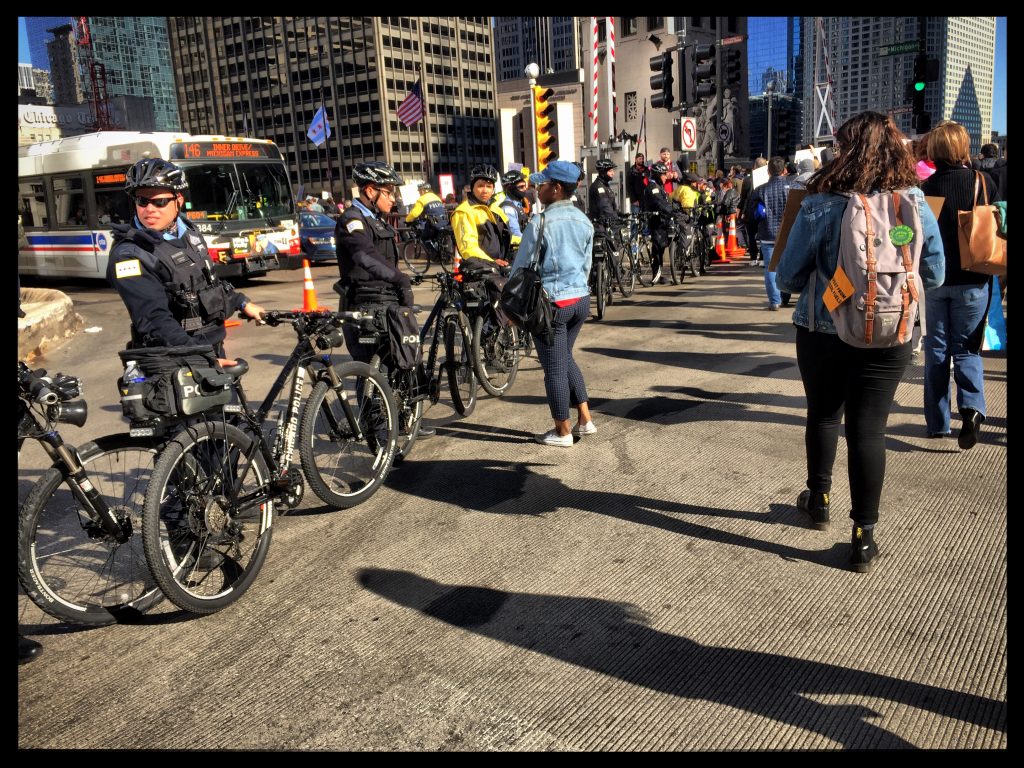

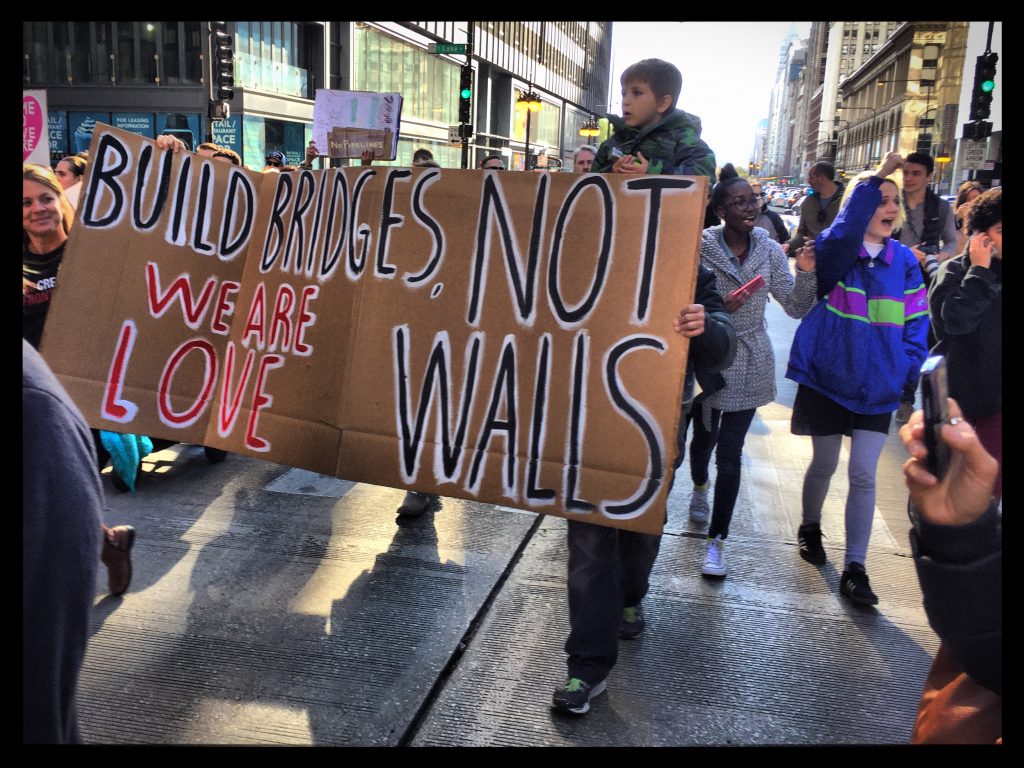

“Our most urgent task is to find the tactics that will move the government no matter how determined it is to resist.” As the #blacklivesmatter movement makes an effort to revive and strengthen the ongoing civil rights movement, creative tactics must emerge that find powerful points of leverage in social and political institutions. A Republican majority House and Senate, especially with Trump in the Whitehouse, are likely to be “determined to resist.” The NYPD has already demonstrated that it is “determined to resist.” Moving entrenched social and political institutions will involve exploring new creative tactics; tactics that avoid ‘permitted’ and ‘police approved’ demonstrations that are confined to ‘free speech zones’. There have been some truly disruptive tactics emerge so far…several instances of blocking rush hour traffic, as well as widely broadcast “I can’t breathe” t-shirts on NBA players, and the collective sourcing of teaching materials with #fergusonsyllabus among many others.

While I end with a final quote I encourage you to take the time to read the full text below. Fifty years later and much of what Dr. Martin Luther King spoke of, much of what he called for social scientists to do, still rings true and still should serve as a call to action, a call to do more.

“There are some things concerning which we must always be maladjusted if we are to be people of good will. We must never adjust ourselves to racial discrimination and racial segregation.”

– Teach well, it matters.

. . .

The Role of the Behavioral Scientist in the Civil Rights Movement

Martin Luther King Jr.

It is always a very rich and rewarding experience when I can take a brief break from the day-to-day demands of our struggle for freedom and human dignity and discuss the issues involved in that struggle with concerned friends of good will all over the nation. It is particularly a great privilege to discuss these issues with members of the academic community, who are constantly writing about and dealing with the problems that we face and who have the tremendous responsibility of molding the minds of young men and women all over the country.

The Civil Rights Movement needs the help of social scientists.

In the preface to their book, ‘Applied Sociology’ (1965), S. M. Miller and Alvin Gouldner state: ‘It is the historic mission of the social sciences to enable mankind to take possession of society.’ It follows that for Negroes who substantially are excluded from society this science is needed even more desperately than for any other group in the population.

For social scientists, the opportunity to serve in a life-giving purpose is a humanist challenge of rare distinction. Negroes too are eager for a rendezvous with truth and discovery. We are aware that social scientists, unlike some of their colleagues in the physical sciences, have been spared the grim feelings of guilt that attended the invention of nuclear weapons of destruction. Social scientists, in the main, are fortunate to be able to extirpate evil, not to invent it.

If the Negro needs social sciences for direction and for self-understanding, the white society is in even more urgent need. White America needs to understand that it is poisoned to its soul by racism and the understanding needs to be carefully documented and consequently more difficult to reject. The present crisis arises because although it is historically imperative that our society take the next step to equality, we find ourselves psychologically and socially imprisoned. All too many white Americans are horrified not with conditions of Negro life but with the product of these conditions-the Negro himself.

White America is seeking to keep the walls of segregation substantially intact while the evolution of society and the Negro’s desperation is causing them to crumble. The white majority, unprepared and unwilling to accept radical structural change, is resisting and producing chaos while complaining that if there were no chaos orderly change would come.

Negroes want the social scientist to address the white community and ‘tell it like it is.’ White America has an appalling lack of knowledge concerning the reality of Negro life. One reason some advances were made in the South during the past decade was the discovery by northern whites of the brutal facts of southern segregated life. It was the Negro who educated the nation by dramatizing the evils through nonviolent protest. The social scientist played little or no role in disclosing truth. The Negro action movement with raw courage did it virtually alone. When the majority of the country could not live with the extremes of brutality they witnessed, political remedies were enacted and customs were altered.

These partial advances were, however, limited principally to the South and progress did not automatically spread throughout the nation. There was also little depth to the changes. White America stopped murder, but that is not the same thing as ordaining brotherhood; nor is the ending of lynch rule the same thing as inaugurating justice.

After some years of Negro-white unity and partial success, white America shifted gears and went into reverse. Negroes, alive with hope and enthusiasm, ran into sharply stiffened white resistance at all levels and bitter tensions broke out in sporadic episodes of violence. New lines of hostility were drawn and the era of good feeling disappeared.

The decade of 1955 to 1965, with its constructive elements, misled us. Everyone, activists and social scientists, underestimated the amount of violence and rage Negroes were suppressing and the amount of bigotry the white majority was disguising.

Science should have been employed more fully to warn us that the Negro, after 350 years of handicaps, mired in an intricate network of contemporary barriers, could not be ushered into equality by tentative and superficial changes.

Mass nonviolent protests, a social invention of Negroes, were effective in Montgomery, Birmingham and Selma in forcing national legislation which served to change Negro life sufficiently to curb explosions. But when changes were confined to the South alone, the North, in the absence of change, began to seethe.

The freedom movement did not adapt its tactics to the different and unique northern urban conditions. It failed to see that nonviolent marches in the South were forms of rebellion. When Negroes took over the streets and shops, southern society shook to its roots. Negroes could contain their rage when they found the means to force relatively radical changes in their environment.

In the North, on the other hand, street demonstrations were not even a mild expression of militancy. The turmoil of cities absorbs demonstrations as merely transitory drama which is ordinary in city life. Without a more effective tactic for upsetting the status quo, the power structure could maintain its intransigence and hostility. Into the vacuum of inaction, violence and riots flowed and a new period opened.

Urban riots.

Urban riots must now be recognized as durable social phenomena. They may be deplored, but they are there and should be understood. Urban riots are a special form of violence. They are not insurrections. The rioters are not seeking to seize territory or to attain control of institutions. They are mainly intended to shock the white community. They are a distorted form of social protest. The looting which is their principal feature serves many functions. It enables the most enraged and deprived Negro to take hold of consumer goods with the ease the white man does by using his purse. Often the Negro does not even want what he takes; he wants the experience of taking. But most of all, alienated from society and knowing that this society cherishes property above people, he is shocking it by abusing property rights. There are thus elements of emotional catharsis in the violent act. This may explain why most cities in which riots have occurred have not had a repetition, even though the causative conditions remain. It is also noteworthy that the amount of physical harm done to white people other than police is infinitesimal and in Detroit whites and Negroes looted in unity.

A profound judgment of today’s riots was expressed by Victor Hugo a century ago. He said, ‘If a soul is left in the darkness, sins will be committed. The guilty one is not he who commits the sin, but he who causes the darkness.’

The policymakers of the white society have caused the darkness; they create discrimination; they structured slums; and they perpetuate unemployment, ignorance and poverty. It is incontestable and deplorable that Negroes have committed crimes; but they are derivative crimes. They are born of the greater crimes of the white society. When we ask Negroes to abide by the law, let us also demand that the white man abide by law in the ghettos. Day-in and day-out he violates welfare laws to deprive the poor of their meager allotments; he flagrantly violates building codes and regulations; his police make a mockery of law; and he violates laws on equal employment and education and the provisions for civic services. The slums are the handiwork of a vicious system of the white society; Negroes live in them but do not make them any more than a prisoner makes a prison. Let us say boldly that if the violations of law by the white man in the slums over the years were calculated and compared with the law-breaking of a few days of riots, the hardened criminal would be the white man. These are often difficult things to say but I have come to see more and more that it is necessary to utter the truth in order to deal with the great problems that we face in our society.

Vietnam War.

There is another cause of riots that is too important to mention casually-the war in Vietnam. Here again, we are dealing with a controversial issue. But I am convinced that the war in Vietnam has played havoc with our domestic destinies. The bombs that fall in Vietnam explode at home. It does not take much to see what great damage this war has done to the image of our nation. It has left our country politically and morally isolated in the world, where our only friends happen to be puppet nations like Taiwan, Thailand and South Korea. The major allies in the world that have been with us in war and peace are not with us in this war. As a result we find ourselves socially and politically isolated.

The war in Vietnam has torn up the Geneva Accord. It has seriously impaired the United Nations. It has exacerbated the hatreds between continents, and worse still, between races. It has frustrated our development at home by telling our underprivileged citizens that we place insatiable military demands above their most critical needs. It has greatly contributed to the forces of reaction in America, and strengthened the military-industrial complex, against which even President Eisenhower solemnly warned us. It has practically destroyed Vietnam, and left thousands of American and Vietnamese youth maimed and mutilated. And it has exposed the whole world to the risk of nuclear warfare.

As I looked at what this war was doing to our nation, and to the domestic situation and to the Civil Rights movement, I found it necessary to speak vigorously out against it. My speaking out against the war has not gone without criticisms. There are those who tell me that I should stick with civil rights, and stay in my place. I can only respond that I have fought too hard and long to end segregated public accommodations to segregate my own moral concerns. It is my deep conviction that justice is indivisible, that injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. For those who tell me I am hurting the Civil Rights movement, and ask, ‘Don’t you think that in order to be respected, and in order to regain support, you must stop talking against the war?’ I can only say that I am not a consensus leader. I do not seek to determine what is right and wrong by taking a Gallop Poll to determine majority opinion. And it is again my deep conviction that ultimately a genuine leader is not a searcher of consensus, but a molder of consensus. On some positions cowardice asks the question, ‘Is it safe?!’ Expediency asks the question, ‘Is it politic?’ Vanity asks the question, ‘Is it popular?’ But conscience must ask the question, ‘Is it right?!’ And there comes a time when one must take a stand that is neither safe, nor politic, nor popular. But one must take it because it is right. And that is where I find myself today.

Moreover, I am convinced, even if war continues, that a genuine massive act of concern will do more to quell riots than the most massive deployment of troops.

Unemployment.

The unemployment of Negro youth ranges up to 40 percent in some slums. The riots are almost entirely youth events-the age range of participants is from 13 to 25. What hypocrisy it is to talk of saving the new generation-to make it the generation of hope-while consigning it to unemployment and provoking it to violent alternatives.

When our nation was bankrupt in the thirties we created an agency to provide jobs to all at their existing level of skill. In our overwhelming affluence today what excuse is there for not setting up a national agency for full employment immediately?

The other program which would give reality to hope and opportunity would be the demolition of the slums to be replaced by decent housing built by residents of the ghettos.

These programs are not only eminently sound and vitally needed, but they have the support of an overwhelming majority of the nation-white and Negro. The Harris Poll on August 21, 1967, disclosed that an astounding 69 percent of the country support a works program to provide employment to all and an equally astonishing 65 percent approve a program to tear down the slums.

There is a program and there is heavy majority support for it. Yet, the administration and Congress tinker with trivial proposals to limit costs in an extravagant gamble with disaster.

The President has lamented that he cannot persuade Congress. He can, if the will is there, go to the people, mobilize the people’s support and thereby substantially increase his power to persuade Congress. Our most urgent task is to find the tactics that will move the government no matter how determined it is to resist.

Civil disobedience.

I believe we will have to find the militant middle between riots on the one hand and weak and timid supplication for justice on the other hand. That middle ground, I believe, is civil disobedience. It can be aggressive but nonviolent; it can dislocate but not destroy. The specific planning will take some study and analysis to avoid mistakes of the past when it was employed on too small a scale and sustained too briefly.

Civil disobedience can restore Negro-white unity. There have been some very important sane white voices even during the most desperate moments of the riots. One reason is that the urban crisis intersects the Negro crisis in the city. Many white decision-makers may care little about saving Negroes, but they must care about saving their cities. The vast majority of production is created in cities; most white Americans live in them. The suburbs to which they flee cannot exist detached from cities. Hence powerful white elements have goals that merge with ours.

Role for the social scientist.

Now there are many roles for social scientists in meeting these problems. Kenneth Clark has said that Negroes are moved by a suicide instinct in riots and Negroes know there is a tragic truth in this observation. Social scientists should also disclose the suicide instinct that governs the administration and Congress in their total failure to respond constructively.

What other areas are there for social scientists to assist the civil rights movement? There are many, but I would like to suggest three because they have an urgent quality.

Social science may be able to search out some answers to the problem of Negro leadership. E. Franklin Frazier, in his profound work, Black Bourgeoisie, laid painfully bare the tendency of the upwardly mobile Negro to separate from his community, divorce himself from responsibility to it, while failing to gain acceptance in the white community. There has been significant improvements from the days Frazier researched, but anyone knowledgeable about Negro life knows its middle class is not yet bearing its weight. Every riot has carried strong overtone of hostility of lower class Negroes toward the affluent Negro and vice versa. No contemporary study of scientific depth has totally studied this problem. Social science should be able to suggest mechanisms to create a wholesome black unity and a sense of peoplehood while the process of integration proceeds.

As one example of this gap in research, there are no studies, to my knowledge, to explain adequately the absence of Negro trade union leadership. Eight-five percent of Negroes are working people. Some two million are in trade unions but in 50 years we have produced only one national leader-A. Philip Randolph.

Discrimination explains a great deal, but not everything. The picture is so dark even a few rays of light may signal a useful direction.

Political action.

The second area for scientific examination is political action. In the past two decades, Negroes have expended more effort in quest of the franchise than they have in all other campaigns combined. Demonstrations, sit-ins and marches, though more spectacular, are dwarfed by the enormous number of man-hours expended to register millions, particularly in the South. Negro organizations from extreme militant to conservative persuasion, Negro leaders who would not even talk to each other, all have been agreed on the key importance of voting. Stokely Carmichael said black power means the vote and Roy Wilkins, while saying black power means black death, also energetically sought the power of the ballot.

A recent major work by social scientists Matthew and Prothro concludes that ‘The concrete benefits to be derived from the franchise-under conditions that prevail in the South-have often been exaggerated.,’ that voting is not the key that will unlock the door to racial equality because ‘the concrete measurable payoffs from Negro voting in the South will not be revolutionary’ (1966).

James A. Wilson supports this view, arguing, ‘Because of the structure of American politics as well as the nature of the Negro community, Negro politics will accomplish only limited objectives’ (1965).

If their conclusion can be supported, then the major effort Negroes have invested in the past 20 years has been in the wrong direction and the major pillar of their hope is a pillar of sand. My own instinct is that these views are essentially erroneous, but they must be seriously examined.

The need for a penetrating massive scientific study of this subject cannot be overstated. Lipset in 1957 asserted that a limitation in focus in political sociology has resulted in a failure of much contemporary research to consider a number of significant theoretical questions. The time is short for social science to illuminate this critically important area. If the main thrust of Negro effort has been, and remains, substantially irrelevant, we may be facing an agonizing crisis of tactical theory.

The third area for study concerns psychological and ideological changes in Negroes. It is fashionable now to be pessimistic. Undeniably, the freedom movement has encountered setbacks. Yet I still believe there are significant aspects of progress.

Negroes today are experiencing an inner transformation that is liberating them from ideological dependence on the white majority. What has penetrated substantially all strata of Negro life is the revolutionary idea that the philosophy and morals of the dominant white society are not holy or sacred but in all too many respects are degenerate and profane.

Negroes have been oppressed for centuries not merely by bonds of economic and political servitude. The worst aspect of their oppression was their inability to question and defy the fundamental precepts of the larger society. Negroes have been loath in the past to hurl any fundamental challenges because they were coerced and conditioned into thinking within the context of the dominant white ideology. This is changing and new radical trends are appearing in Negro thought. I use radical in its broad sense to refer to reaching into roots.

Ten years of struggle have sensitized and opened the Negro’s eyes to reaching. For the first time in their history, Negroes have become aware of the deeper causes for the crudity and cruelty that governed white society’s responses to their needs. They discovered that their plight was not a consequence of superficial prejudice but was systemic.

The slashing blows of backlash and frontlash have hurt the Negro, but they have also awakened him and revealed the nature of the oppressor. To lose illusions is to gain truth. Negroes have grown wiser and more mature and they are hearing more clearly those who are raising fundamental questions about our society whether the critics be Negro or white. When this process of awareness and independence crystallizes, every rebuke, every evasion, become hammer blows on the wedge that splits the Negro from the larger society.

Social science is needed to explain where this development is going to take us. Are we moving away, not from integration, but from the society which made it a problem in the first place? How deep and at what rate of speed is this process occurring? These are some vital questions to be answered if we are to have a clear sense of our direction.

We know we haven’t found the answers to all forms of social change. We know, however, that we did find some answers. We have achieved and we are confident. We also know we are confronted now with far greater complexities and we have not yet discovered all the theory we need.

And may I say together, we must solve the problems right here in America. As I have said time and time again, Negroes still have faith in America. Black people still have faith in a dream that we will all live together as brothers in this country of plenty one day.

But I was distressed when I read in the New York Times of Aug. 31, 1967; that a sociologist from Michigan State University, the outgoing president of the American Sociological Society, stated in San Francisco that Negroes should be given a chance to find an all Negro community in South America: ‘that the valleys of the Andes Mountains would be an ideal place for American Negroes to build a second Israel.’ He further declared that ‘The United States Government should negotiate for a remote but fertile land in Equador, Peru or Bolivia for this relocation.’

I feel that it is rather absurd and appalling that a leading social scientist today would suggest to black people, that after all these years of suffering an exploitation as well as investment in the American dream, that we should turn around and run at this point in history. I say that we will not run! Professor Loomis even compared the relocation task of the Negro to the relocation task of the Jews in Israel. The Jews were made exiles. They did not choose to abandon Europe, they were driven out. Furthermore, Israel has a deep tradition, and Biblical roots for Jews. The Wailing Wall is a good example of these roots. They also had significant financial aid from the United States for the relocation and rebuilding effort. What tradition does the Andes, especially the valley of the Andes Mountains, have for Negroes?

And I assert at this time that once again we must reaffirm our belief in building a democratic society, in which blacks and whites can live together as brothers, where we will all come to see that integration is not a problem, but an opportunity to participate in the beauty of diversity.

The problem is deep. It is gigantic in extent, and chaotic in detail. And I do not believe that it will be solved until there is a kind of cosmic discontent enlarging in the bosoms of people of good will all over this nation.

There are certain technical words in every academic discipline which soon become stereotypes and even clichés. Every academic discipline has its technical nomenclature. You who are in the field of psychology have given us a great word. It is the word maladjusted. This word is probably used more than any other word in psychology. It is a good word; certainly it is good that in dealing with what the word implies you are declaring that destructive maladjustment should be destroyed. You are saying that all must seek the well-adjusted life in order to avoid neurotic and schizophrenic personalities.

But on the other hand, I am sure that we will recognize that there are some things in our society, some things in our world, to which we should never be adjusted. There are some things concerning which we must always be maladjusted if we are to be people of good will. We must never adjust ourselves to racial discrimination and racial segregation. We must never adjust ourselves to religious bigotry. We must never adjust ourselves to economic conditions that take necessities from the many to give luxuries to the few. We must never adjust ourselves to the madness of militarism, and the self-defeating effects of physical violence.

In a day when Sputniks, Explorers and Geminies are dashing through outer space, when guided ballistic missiles are carving highways of death through the stratosphere, no nation can finally win a war. It is no longer a choice between violence and nonviolence, it is either nonviolence or nonexistence. As President Kennedy declared, ‘Mankind must put an end to war, or war will put an end to mankind.’ And so the alternative to disarmament, the alternative to a suspension in the development and use of nuclear weapons, the alternative to strengthening the United Nations and eventually disarming the whole world, may well be a civilization plunged into the abyss of annihilation. Our earthly habitat will be transformed into an inferno that even Dante could not envision.

Creative maladjustment.

Thus, it may well be that our world is in dire need of a new organization, The International Association for the Advancement of Creative Maladjustment. Men and women should be as maladjusted as the prophet Amos, who in the midst of the injustices of his day, could cry out in words that echo across the centuries, ‘Let justice roll down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream’; or as maladjusted as Abraham Lincoln, who in the midst of his vacillations finally came to see that this nation could not survive half slave and half free; or as maladjusted as Thomas Jefferson, who in the midst of an age amazingly adjusted to slavery, could scratch across the pages of history, words lifted to cosmic proportions, ‘We hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal. That they are endowed by their creator with certain inalienable rights. And that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.’ And through such creative maladjustment, we may be able to emerge from the bleak and desolate midnight of man’s inhumanity to man, into the bright and glittering daybreak of freedom and justice.

I have not lost hope. I must confess that these have been very difficult days for me personally. And these have been difficult days for every civil rights leader, for every lover of justice and peace.

. . .

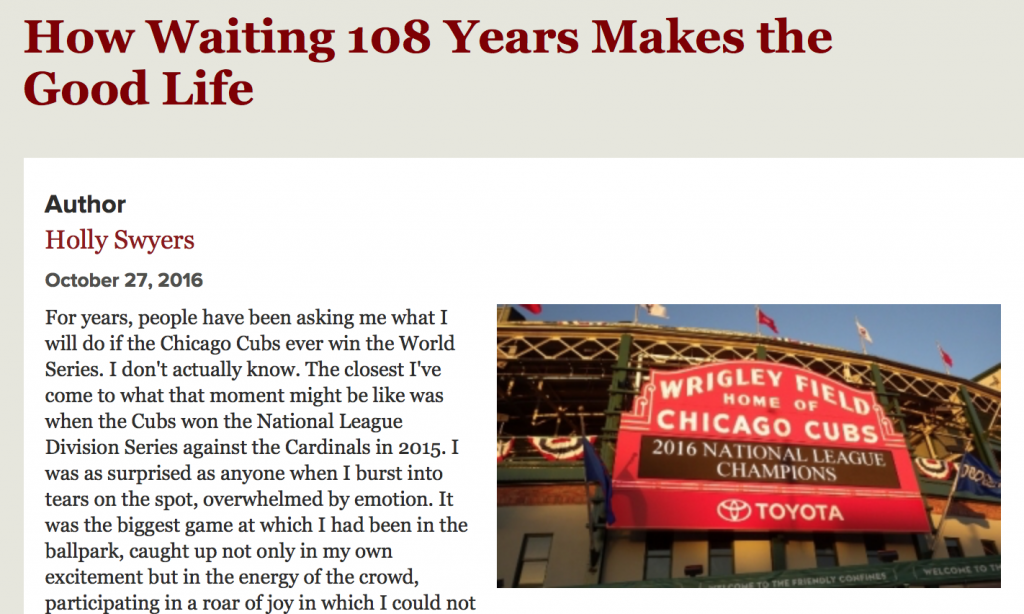

We celebrated the Cubs’ amazing season and World Series victory with a guest post from a colleague and anthropologist, Holly Swyers:

We celebrated the Cubs’ amazing season and World Series victory with a guest post from a colleague and anthropologist, Holly Swyers: