Going to college is sold as the primary pathway to upward economic mobility, but is that true?

In today’s world, a college degree is widely understood as the ticket to success, but do universities actually contribute to the maintenance of class structures…reproducing an increasingly stratified system?

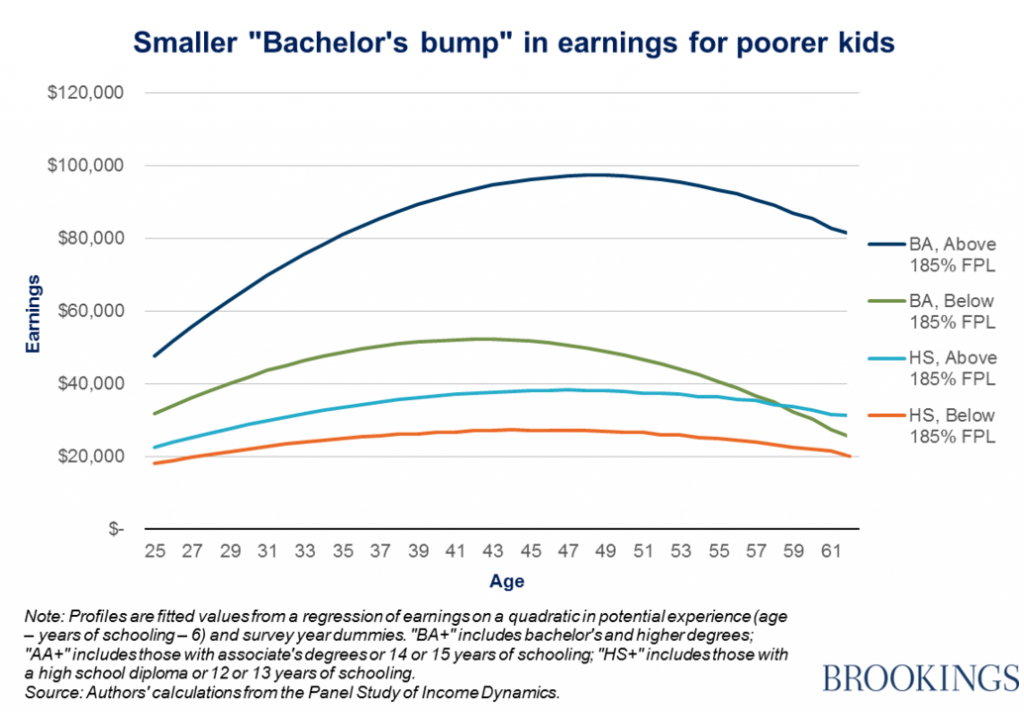

There are several interesting sources that question the traditional view of a college as the “great leveler”. Recent analysis of the Panel Study on Income Dynamics by The Brookings Institution shows that while students from both poor and not-poor families see an increase in their incomes, those from poor families see a smaller proportional increase. The report states, “college graduates from families with an income below 185 percent of the federal poverty level (the eligibility threshold for the federal assisted lunch program) earn 91 percent more over their careers than high school graduates from the same income group. By comparison, college graduates from families with incomes above 185 percent of the FPL earned 162 percent more over their careers (between the ages of 25 and 62) than those with just a high school diploma.” In the figure below, those from poor families that earn a BA, the green line, earn more over the life course than both those from poor and not poor families with just a high school diploma. However, looking at the navy blue line, those from non-poor families that earn a BA see a much larger proportional increase in their life course earnings compared to those from non-poor families that have just a high school diploma.

In the figure above, you can also see that at the peak of their career and income earning, around age 43, those with a BA from poor families, on average, earn only slightly more (around $53,000) than the average BA holder from non-poor families did at age 25! So, college pays off in regards to lifetime earnings, but it pays off even more for those who earn a degree and are from non-poor families. On average, they end up in a much better place socio-economically than those from poor families that earned the same level of credential.

A tremendously interesting and well-done book from a couple of sociologists gives us one explanation of why the structure of some institutions reproduces class rather than “levels the field”. Elizabeth Armstrong and Laura Hamilton‘s 2013 book, Paying for the Party, is an ethnography following all the women on a dorm floor at a large, midwestern, state university for five years. The women enter the university with different socio-economic statuses and many of those who come from lower income families (mostly from within the state) leave four to five years later in debt and move back to their hometowns with little upward mobility on the immediate horizon. The young women who come from wealthier families (most from out of state) leave the university and move to major metropolitan areas like Chicago or New York City while at least maintaining their higher income status.

A tremendously interesting and well-done book from a couple of sociologists gives us one explanation of why the structure of some institutions reproduces class rather than “levels the field”. Elizabeth Armstrong and Laura Hamilton‘s 2013 book, Paying for the Party, is an ethnography following all the women on a dorm floor at a large, midwestern, state university for five years. The women enter the university with different socio-economic statuses and many of those who come from lower income families (mostly from within the state) leave four to five years later in debt and move back to their hometowns with little upward mobility on the immediate horizon. The young women who come from wealthier families (most from out of state) leave the university and move to major metropolitan areas like Chicago or New York City while at least maintaining their higher income status.

The reasons for this outcome are complex (book length in fact), but revolve around the social capital of the wealthier young women’s families – helping them, for example, get internships at firms in entertainment and fashion industries. Also, advantages in financial capital allow those from wealthier families to navigate the demands of the dominant and expensive sorority social scene while not having to maintain employment during school. This results in the wealthier women leaving college with less debt and subsequently having the ability to accept unpaid internships, and live in expensive metro areas where there is more higher-income-opportunity. The women from wealthier families also have the cultural capital to successfully deploy their “erotic status” in the alcohol-laden, male-controlled, less-institutionally-scrutinized fraternity party scene. This keeps them safer and at lower risk of having their collegiate career derailed by sexual assault.

The university in this study (and likely others with similar characteristics) contributes to this by, at a minimum, turning a blind eye to the fraternity party scene, providing few real alternative social paths for students to pursue, and providing only limited opportunities to participate in honors programs that have smaller class sizes and access to mentoring from faculty. In essence, students are pushed into the fraternity party scene or risk social isolation and subsequent mental health problems. Additionally, the university maintains a series of “easy” majors in the entertainment and fashion industry for those that want to spend more time in the dominant social scene. These easy majors are attractive to students from all families, except it is only those from wealthier families that can parlay such majors into actual employment upon graduation (how many sports broadcasting positions are there really?).

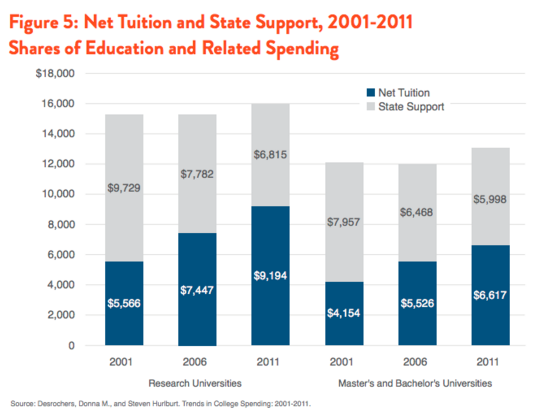

The university maintains this structure in order to attract out-of-state student tuition dollars by offering the “classic” big college experience – major college sports, an extensive fraternity and sorority system, and strong social traditions in annual events. The out-of-state dollars are needed by the universities in light of ever decreasing state budget contributions.

Therefore, the structure of the institution itself leads to the maintenance of class. For a more detailed review of this book see my full forthcoming (April) review in Teaching Sociology. I use Paying for the Party in my Introduction to Sociology & Anthropology courses and highly recommend it for both its academic and practical lessons to students at any type of institution.

A recent article by Jason Houle, examines the differences in student loan debt across different levels of parental socioeconomic status (SES). He finds that students from high-income families have 240% less debt than students from lower-income families. The more educated their parents are, the less debt that students accrue – those with at least one college-educated parent have 54% less debt than those students with neither parent holding a college degree. Among those that have very high levels of student loan debt, “those from low-income and less educated backgrounds are more likely than their more advantaged counterparts to take on very high levels of debt” (62). Read more about student loan debt from Jason Houle on the Society Pages here.

While the Brookings data is on income, students from lower income families likely take on more student loan debt, that combined with lower income earnings may result in delayed home ownership which is one of the primary avenues of wealth accumulation in the US. While this makes logic sense, there is no pattern in the data that suggests it is empirically true.

Earning a college degree does improve one’s income over the life course, but proportionally, those that come from families with higher incomes see a larger gain than those that come from poor families. Sociology helps us understand why that remains true.

Teach well, it matters.

. . .

Comments 2

TOOLS FOR TEACHING SOCIOLOGY: Teach well. It matters. - Sociology Toolbox — December 7, 2016

[…] A PATH TO MOBILITY? How universities maintain the class structure Going to college is sold as the primary pathway to upward economic mobility, but is that true? In today’s world, a college degree is widely understood as the ticket to success, but do universities actually contribute to the maintenance of class structures…reproducing an increasingly stratified system? […]

Christina — December 21, 2019

I like their activities