Dr. Barbara Weissberger is an emerita professor in the University of Minnesota’s Department of Spanish and Portuguese Studies. Next month, she will be presenting her work at the Blood Libel Then & Now: The Enduring Impact of an Imaginary Event conference in New York City.

The Edict of Expulsion of all unconverted Jews that Queen Isabel and King Fernando issued in April of 1492 ended more than a millennium of co-existence between Christians and Jews in the Spanish kingdoms. Between 1391 and 1413 that often fragile co-existence began to unravel when real and threatened violence against Jews caused a massive wave of conversion to Christianity, creating a diverse group known as conversos. Prior to the conversions, blood libel accusations against Jews in Spain, unlike in the rest of Europe, had been exceedingly rare.

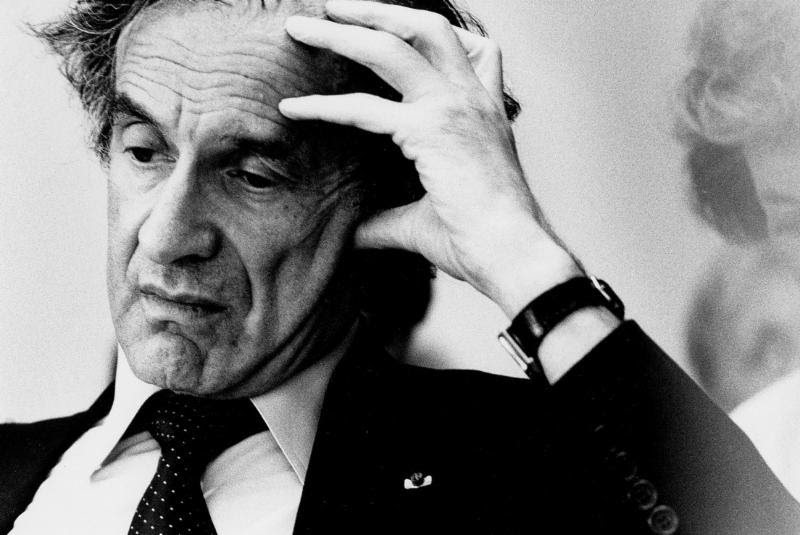

There are many that contend today that the Holocaust’s global presence and iconic status obscures other forms of mass violence, and even the acknowledgment of other genocides. Elie Wiesel’s seminal role in Holocaust memorialization worldwide demonstrates exactly the opposite. The proliferation of Holocaust remembrance, education and research efforts has been extraordinarily influential in the moral and political debates about atrocities, and in raising the level of attention to past violence and responsiveness to present genocide and other forms of gross human rights violations.

There are many that contend today that the Holocaust’s global presence and iconic status obscures other forms of mass violence, and even the acknowledgment of other genocides. Elie Wiesel’s seminal role in Holocaust memorialization worldwide demonstrates exactly the opposite. The proliferation of Holocaust remembrance, education and research efforts has been extraordinarily influential in the moral and political debates about atrocities, and in raising the level of attention to past violence and responsiveness to present genocide and other forms of gross human rights violations. Elie Wiesel had a profound effect on my life. In 1997 I embarked on a journey to earn my Master’s degree from the University of Minnesota. At the time that I began my classes I had no thoughts of studying the Holocaust, but through a series of small events, I found myself thinking of nothing else. I do not remember when I read Night, nor do I recall what led me to return to Wiesel’s work while in graduate school. For some reason I turned to a little known collection of his short stories titled One Generation After, published in 1970. How the book found its way from my mother’s bookshelf to mine is not clear, but for some reason, I picked it up and read it. The story that changed my life was “The Watch.” Over the course of six pages, Wiesel tells of his return to his home of Sighet, Romania and the clandestine mission he undertakes to recover the watch given to him by his parents on the eve of his Bar Mitzvah. It is the last gift he received prior to being transported with his family to Auschwitz. Like many Jewish families, fearing the unknown and hoping for an eventual return, he buried it in the backyard of their home. Miraculously, he finds it, and quickly begins to dream of bringing it back to life. However, in the end he decides to put it back in its resting place. He hopes that some future child will dig it up and realize that once Jewish children had lived and sadly been robbed of their lives there. For Wiesel the town is no longer another town, it is the face of that watch.

Elie Wiesel had a profound effect on my life. In 1997 I embarked on a journey to earn my Master’s degree from the University of Minnesota. At the time that I began my classes I had no thoughts of studying the Holocaust, but through a series of small events, I found myself thinking of nothing else. I do not remember when I read Night, nor do I recall what led me to return to Wiesel’s work while in graduate school. For some reason I turned to a little known collection of his short stories titled One Generation After, published in 1970. How the book found its way from my mother’s bookshelf to mine is not clear, but for some reason, I picked it up and read it. The story that changed my life was “The Watch.” Over the course of six pages, Wiesel tells of his return to his home of Sighet, Romania and the clandestine mission he undertakes to recover the watch given to him by his parents on the eve of his Bar Mitzvah. It is the last gift he received prior to being transported with his family to Auschwitz. Like many Jewish families, fearing the unknown and hoping for an eventual return, he buried it in the backyard of their home. Miraculously, he finds it, and quickly begins to dream of bringing it back to life. However, in the end he decides to put it back in its resting place. He hopes that some future child will dig it up and realize that once Jewish children had lived and sadly been robbed of their lives there. For Wiesel the town is no longer another town, it is the face of that watch.