After concerted efforts by the Economic Community of Central African States, Prime Minister Djotodia, stepped down last week following a two-day summit in Chad. This concluded the shuttle diplomacy by Ambassador Power and concerted efforts by Secretary of State Madeleine Albright to raise awareness of what was happening in CAR. His replacement, Mr. Alexandre-Ferdinand Nguendet is the former speaker of parliament and upon his ascension to office has claimed that violence has largely subsided. more...

News

It is with great sadness that the Center for Holocaust and Genocide announces the passing of Gus Gutman. We recently had the pleasure of working with Gus on the “Portraying Memories” project with artist Felix de la Concha. Gus was an enthusiastic participant, turning what is typically a 2-4 hour session into a daylong adventure involving a trip to the Shalom Home, where he introduced Felix to his good friend Walter Schwartz, so he could participate as well.

Something insidious, but sadly not unexpected, is happening in the Central African Republic (CAR)-over the past twelve months mass killings have been taking place in the CAR, a former French colony in a very rough neighborhood (it borders the Sudan’s to the East, Chad to the North, and DRC to the South). Things came to a head in March when the former president Francois Bozizé was deposed by a group of Muslim militants (Séléka) whom instigated sectarian killings and human rights abuses against the largely Christian populace. This has resulted in the formation of self-defense groups (Anti-balaka meaning ‘sword/machete’ in the Sango language) formed to protect the victims. This conflict is complicated by the fact that there are claims of the Séléka getting support from mercenaries in Sudan and Chad.

Myron Kunin passed away at the age of 85 last week. It was Myron’s passion for art that brought him together with Stephen Feinstein. Together they curated Witness and Legacy, a major commemorative art exhibition to mark the 50th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz that debuted in St. Paul in 1995 and traveled until 2002. That collaboration began the friendship and vision that lead to the founding of our Center in 1997.

We will honor Myron’s his legacy as we strive to fulfill our mission of educating all sectors of society about the Holocaust and other genocides.

May his memory be a blessing to us all.

Obituary: Myron Kunin, businessman, patron of the arts

Star Tribune 10-31-2013

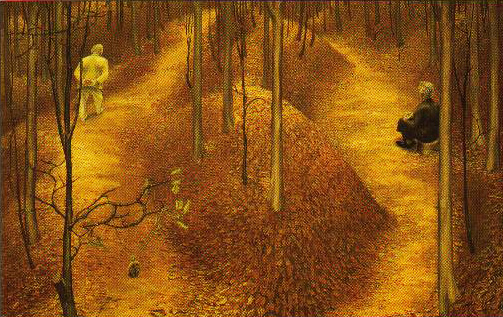

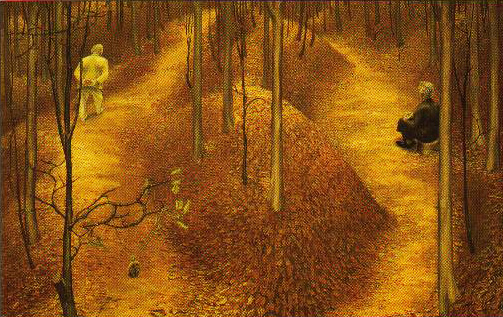

My Parents II, 1946. Henry Koerner (1915-1991)

This painting from Myron Kunin’s collection has been associated with the Center since it was used to promote the Absence/Presence exhibition of 1999. It was also used as the cover photo for Dr. Stephen Feinstein’s book of the same name.

“Students here seem to have a more emotional connection to the Holocaust”

Falko Schmieder is a DAAD visiting professor at the University of Minnesota and is currently teaching the course “History of the Holocaust.” He has studied Communications, Political Science and Sociology at various German Universities. Since 2005 he has worked as a researcher at the Center for Literary and Cultural Research Berlin. Together with Matthias Rothe, the course “Adorno, Foucault, and beyond” is being offered through the Department of German, Scandinavian and Dutch. Falko Schmieder will give a lecture at the CHGS Library (room 710 Social Sciences) on The Concept of Survival on November 20th at 12 p.m. more...

Falko Schmieder is a DAAD visiting professor at the University of Minnesota and is currently teaching the course “History of the Holocaust.” He has studied Communications, Political Science and Sociology at various German Universities. Since 2005 he has worked as a researcher at the Center for Literary and Cultural Research Berlin. Together with Matthias Rothe, the course “Adorno, Foucault, and beyond” is being offered through the Department of German, Scandinavian and Dutch. Falko Schmieder will give a lecture at the CHGS Library (room 710 Social Sciences) on The Concept of Survival on November 20th at 12 p.m. more...

Last June, the allegation that a 94 year old Ukrainian immigrant living in Northeast Minneapolis could have been a top commander of a Nazi- SS lead unit, received international media attention. The public’s response was polarized as for as many who felt justice needed to be served there were just as many who felt that we should leave him alone. Should a person’s chronological age prevent them from being accountable for their crimes? more...

The CHGS Blog now has a Student Opportunities page! This page will be central location for students to find Calls for Papers, Conference Announcements, Funding Opportunities, and other resources.

Have anything you’d like to add?

Please send info to chgs@umn.edu

Memory is a tricky thing. Biased and imperfect, it can be willfully deceitful and innocently forgetful. Collective memory is no different, and is perhaps more problematic in that it is often formed and framed by people and institutions with ulterior motives. Even more importantly, collective memory defines our popular conceptions of history’s meaning.

Popular histories are powerful forces in shaping identity and purpose for all societies. Yet, they rarely do justice to the delicate intricacies of the central questions that the pressing issues of human existence ask of us. Popular history marginalizes some of the most essential questions that we face, and yet, it is often the only history to which many young people are exposed. more...

“If I am not for myself, then who will be for me? And if I am only for myself, then what am I? And if not now, when?” said Rabbi Hillel, one of the most influential sages and scholars in Jewish history.

It is unlikely that Barak Obama had this phrase of the Talmud in mind last week during the Moscow’s G8 summit. However, he seems to have performed a political interpretation of this often quoted Jewish aphorism when he tried to convince his fellow world leaders of the necessity of joint military action against the criminal Assad regime in Syria. more...

The startled reaction to the news that Michael Karkoc, an alleged former Nazi is living in Northeast Minneapolis is understandable. To have a Nazi in our midst is unsettling and leads to the larger question of how it is possible for someone who (if found guilty of war crimes) could have lived in the Twin Cities for 70 years undetected.

It is with great sadness that the Center for Holocaust and Genocide announces the passing of Gus Gutman. We recently had the pleasure of working with Gus on the “Portraying Memories” project with artist Felix de la Concha. Gus was an enthusiastic participant, turning what is typically a 2-4 hour session into a daylong adventure involving a trip to the Shalom Home, where he introduced Felix to his good friend Walter Schwartz, so he could participate as well.

Something insidious, but sadly not unexpected, is happening in the Central African Republic (CAR)-over the past twelve months mass killings have been taking place in the CAR, a former French colony in a very rough neighborhood (it borders the Sudan’s to the East, Chad to the North, and DRC to the South). Things came to a head in March when the former president Francois Bozizé was deposed by a group of Muslim militants (Séléka) whom instigated sectarian killings and human rights abuses against the largely Christian populace. This has resulted in the formation of self-defense groups (Anti-balaka meaning ‘sword/machete’ in the Sango language) formed to protect the victims. This conflict is complicated by the fact that there are claims of the Séléka getting support from mercenaries in Sudan and Chad.

Myron Kunin passed away at the age of 85 last week. It was Myron’s passion for art that brought him together with Stephen Feinstein. Together they curated Witness and Legacy, a major commemorative art exhibition to mark the 50th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz that debuted in St. Paul in 1995 and traveled until 2002. That collaboration began the friendship and vision that lead to the founding of our Center in 1997.

We will honor Myron’s his legacy as we strive to fulfill our mission of educating all sectors of society about the Holocaust and other genocides.

May his memory be a blessing to us all.

Obituary: Myron Kunin, businessman, patron of the arts

Star Tribune 10-31-2013

My Parents II, 1946. Henry Koerner (1915-1991)

This painting from Myron Kunin’s collection has been associated with the Center since it was used to promote the Absence/Presence exhibition of 1999. It was also used as the cover photo for Dr. Stephen Feinstein’s book of the same name.

“Students here seem to have a more emotional connection to the Holocaust”

Falko Schmieder is a DAAD visiting professor at the University of Minnesota and is currently teaching the course “History of the Holocaust.” He has studied Communications, Political Science and Sociology at various German Universities. Since 2005 he has worked as a researcher at the Center for Literary and Cultural Research Berlin. Together with Matthias Rothe, the course “Adorno, Foucault, and beyond” is being offered through the Department of German, Scandinavian and Dutch. Falko Schmieder will give a lecture at the CHGS Library (room 710 Social Sciences) on The Concept of Survival on November 20th at 12 p.m. more...

Falko Schmieder is a DAAD visiting professor at the University of Minnesota and is currently teaching the course “History of the Holocaust.” He has studied Communications, Political Science and Sociology at various German Universities. Since 2005 he has worked as a researcher at the Center for Literary and Cultural Research Berlin. Together with Matthias Rothe, the course “Adorno, Foucault, and beyond” is being offered through the Department of German, Scandinavian and Dutch. Falko Schmieder will give a lecture at the CHGS Library (room 710 Social Sciences) on The Concept of Survival on November 20th at 12 p.m. more...

Last June, the allegation that a 94 year old Ukrainian immigrant living in Northeast Minneapolis could have been a top commander of a Nazi- SS lead unit, received international media attention. The public’s response was polarized as for as many who felt justice needed to be served there were just as many who felt that we should leave him alone. Should a person’s chronological age prevent them from being accountable for their crimes? more...

Memory is a tricky thing. Biased and imperfect, it can be willfully deceitful and innocently forgetful. Collective memory is no different, and is perhaps more problematic in that it is often formed and framed by people and institutions with ulterior motives. Even more importantly, collective memory defines our popular conceptions of history’s meaning.

Popular histories are powerful forces in shaping identity and purpose for all societies. Yet, they rarely do justice to the delicate intricacies of the central questions that the pressing issues of human existence ask of us. Popular history marginalizes some of the most essential questions that we face, and yet, it is often the only history to which many young people are exposed. more...

“If I am not for myself, then who will be for me? And if I am only for myself, then what am I? And if not now, when?” said Rabbi Hillel, one of the most influential sages and scholars in Jewish history.

It is unlikely that Barak Obama had this phrase of the Talmud in mind last week during the Moscow’s G8 summit. However, he seems to have performed a political interpretation of this often quoted Jewish aphorism when he tried to convince his fellow world leaders of the necessity of joint military action against the criminal Assad regime in Syria. more...

The startled reaction to the news that Michael Karkoc, an alleged former Nazi is living in Northeast Minneapolis is understandable. To have a Nazi in our midst is unsettling and leads to the larger question of how it is possible for someone who (if found guilty of war crimes) could have lived in the Twin Cities for 70 years undetected.