In April of 1994, genocide began in Rwanda. More than one million Tutsi were killed over the course of a mere 100 days; the lasting impact of this violence is immeasurable. Each year, beginning on April 7th, Rwandans across the world come together to reflect and commemorate during the annual Kwibuka remembrance period.

Kwibuka, a Kinyarwanda word that loosely translates as “to remember,” is a period to pay respect to genocide victims and reflect on Rwanda´s history and ways to overcome its legacies of conflict. This week, Kwibuka will begin once again, but the ongoing pandemic means that this time will continue to look very different than previous years.

Before the pandemic, Kwibuka involved many large group gatherings and collective commemorative rituals. The remembrance period customarily begins with a night vigil, a traditional funeral rite in Rwanda, taking place on the eve of actual commemoration. Alongside this comes a “walk to remember” that kicks off other ceremonies at commemorative spaces, like stadiums, memorials, state administrative offices. For the government, Kwibuka gatherings provide a platform to pass on political messages. Annual themes reflecting the government´s vision, like “Remember, Unite, Renew,” can be read on banners across the country.

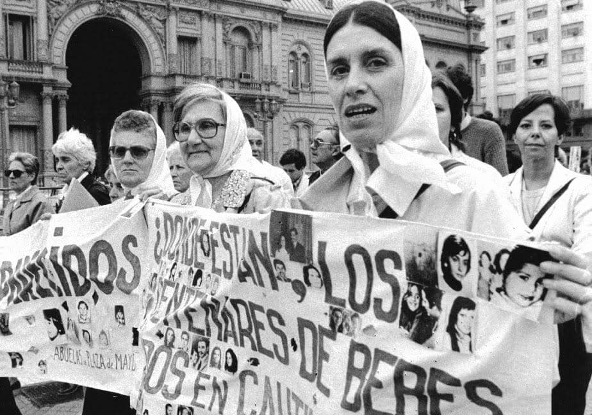

For many genocide survivors, Kwibuka is both an emotionally challenging time and a time to feel spiritually connected with those killed during the genocide through visits to their burial sites. Physical presence at burials and ceremonies like laying wreaths facilitate this connection to loved ones, as Rwandan spiritual tradition holds that communication is possible at the grave of the dead. This mourning generally requires Rwandans to travel to memorials and other sites where their loved ones were killed. Kwibuka can also promote connection within communities through events at the family level, community level, or even within diaspora communities. In normal circumstances, Kwibuka necessitates travel, large group gatherings, and physical closeness – actions that are unsafe during the pandemic.

As author Eric Sibomana wrote last year, COVID-19 has led to significant alterations in commemorative policies in Rwanda. It triggered a shift from physical to digital forms of commemoration, and consequently, the number of mourners attending commemorative ceremonies was reduced. Rituals requiring mass participation were prohibited, and other practices such as the night vigil, a walk to remember, among many others, were canceled to adjust the pandemic regulations.

Last year, the National Commission for the Fight against Genocide (CNLG), the state agency that organizes Kwibuka, called for significant shifts. CNLG Executive Secretary Dr. Jean Damascène Bizimana said, “The official opening of commemoration ceremonies at district levels on April 7 will not take place. All citizens will participate in the commemoration from their homes using TV, radio, and social media.”

Meetings and ceremonies requiring physical contact and large group gatherings were banned and replaced by video conferencing. In addition to the digitalization of memorial rites, CNLG committed to issuing a daily write-up to help mourners catch up with the aired materials. Officials also suggested alternative forms of commemoration during the lockdown. Some of these were collective, like tuning into commemorative television and radio broadcasts. Others encouraged individual acts of remembrance, like lighting a candle or connecting with community members to discuss genocide memory.

Shifts in the organization of genocide commemoration speak to debates in the collective memory literature about the importance of physical presence in solidifying the power of memory in sacred space and ritual. For Randall Collins and his theory of interaction ritual, “bodily co-presence” is a required ingredient to establish the collective efference that makes the ritual outcomes of emotionality, solidarity, and norm-setting possible. Through this lens, shared physical presence enables the power of ritual, and to disrupt this physicality is to sap the ritual of its strength.

Many scholars, however, have advanced alternatives to the necessity of co-presence. Jeffrey Alexander and Katz and Dayan point to the capacity of technology to expand the reach of ritual space. Television and radio have the capacity to broadcast rituals to those who might otherwise not be able to access them.

Further, Campos-Castillo and Hitlin theorize that this reach illustrates the inherent subjectivity of co-presence: not all actors experience shared space in the same way. They argue that the power of co-presence is based upon a feeling of unity, which draws from shared attention, emotion, and action over physical proximity. Rather than a binary between present or not, their work illustrates how traditional rituals also differ for those who experience them.

While scholars debate the impact of shifting to digital forms of commemoration, there are also practical concerns at hand. For example, the pandemic points to the limitations of commemorative mediums that rely on technology. Remote broadcasts are inaccessible to many Rwandans, especially rural inhabitants with limited access to digital platforms or literacy education.

With high rates of illiteracy in rural areas, oral tradition remains a strong means of communication. This suggests the effects of Covid-19 have further isolated the less technologically equipped and illiterate community of mourners in Rwanda, who could not fully participate in commemoration during the pandemic.

COVID restrictions are beginning to lift across the globe, but this year’s Kwibuka will certainly continue to look different than in pre-pandemic years. While many social scientists point to the potential impact of remote commemorative rituals, such commemoration is different in terms of both power and reach.

And further, the case of Rwanda shows how this difference most impacts those who experience economic and educational marginalization. While the pandemic has shown the potential of remote experiences, such inequities are an important reminder that distanced sites of memory are not equally accessible.

Eric Sibomana is a Rwandan scholar, holder of M.A. in Genocide Studies and Prevention, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Vienna- Austria, and a researcher in the European Research Council (ERC) funded project on “Globalized Memorial Museum,” at the Austrian Academy of Science, Institute of Culture Studies and Theatre History. His research interest is in atrocities – war and genocide – their memorialization and musealization politics and dynamics -political, social, cultural, and judicial – attached to them; and in dead body politics. Since 2012, he has worked on national and international projects centered on genocide in Rwanda and its responses – Gacaca jurisdictions, social integration of former perpetrators, and reconciliation. Also, he has served as a research associate at the African Leadership Center (ALC/Nairobi, Kenya) since 2019.

Brooke Chambers is a Ph.D. Candidate in the University of Minnesota’s Department of Sociology. Her research interests include collective memory, political sociology, genocide, and the law. Her dissertation work examines generational trauma in contemporary Rwanda, with a focus on the commemorative process. She was the 2018-2019 recipient of the Badzin Fellowship in Holocaust and Genocide Studies and a 2019-2020 Fulbright Research Fellow.