On December 26, 2012, at 10am, a solemn procession of horses, carrying Dakota men, women and children, will enter Mankato, MN and proceed to a site near the Minnesota River. These riders will have begun their journey in Lower Brule, South Dakota, and no matter the weather, they will ride for sixteen days in order to arrive at precisely this spot at precisely this time. They will gather near a hulking stone statue of a buffalo, across from the Mankato Public Library.

It was on this spot, at precisely this time, that the largest mass execution in American history took place one hundred and fifty years ago. Thirty-eight Dakota akicita (warriors) were simultaneously hung by order of Abraham Lincoln as punishment for their part in the Dakota-US War of 1862. That war, which has mistakenly been called the “Sioux Uprising,” lasted for six weeks from August 18 to late September, 1862; it happened for many complicated reasons, one of which was the failure of the US government to deliver the gold, provisions, and food promised by the treaties in which the Dakota signed away thousands of acres of land. The Dakota were starving. Little Crow, who led the akicita into battle, did so against his better judgment. He had been to Washington, DC, and knew the might of the government and the huge number of Euro-American settlers.

It was on this spot, at precisely this time, that the largest mass execution in American history took place one hundred and fifty years ago. Thirty-eight Dakota akicita (warriors) were simultaneously hung by order of Abraham Lincoln as punishment for their part in the Dakota-US War of 1862. That war, which has mistakenly been called the “Sioux Uprising,” lasted for six weeks from August 18 to late September, 1862; it happened for many complicated reasons, one of which was the failure of the US government to deliver the gold, provisions, and food promised by the treaties in which the Dakota signed away thousands of acres of land. The Dakota were starving. Little Crow, who led the akicita into battle, did so against his better judgment. He had been to Washington, DC, and knew the might of the government and the huge number of Euro-American settlers.

Disease, war, and starvation. These are the three primary factors that caused the genocide of the indigenous people of North America. Historian David Stannard estimates that 16,000,000 native people lived in North America pre-Columbus. By the late 1800’s, only 250,000 remained. As Stannard puts it in his book, American Holocaust, “There was, at last, almost no one left to kill.” Dakota scholar Dr. Chris Mato Nunpa has written and spoken persuasively about how the genocide of Native Americans can be accurately described by the United Nations Convention on Genocide, though, of course, this convention and the very word “genocide” did not exist until after World War II.

In 1862, the population of Mankato was roughly 400 people, but 4,000 whites came to observe the spectacle of the hanging. The hastily buried bodies of the Dakota men where dug up by physicians eager to use their corpses for experimentation. In subsequent decades, beer ads carried images of the hanging as did metal trays used in bars. This year’s commemoration will be a more sober, somber affair and, it is hoped, will bring deeper understanding of the complexities of this profoundly sad moment in American history.

Dr. Elizabeth Baer, Professor of English and Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Gustavus Adolphus College, recently completed teaching the course: “Commemorating Controversy: the US-Dakota War of 1862,” which was accompanied by a six-part lecture series open to the general public in January of 2012.

See the upcoming art exhibition, “Hena Uŋkiksuyapi: In Commemoration of the Dakota Mass Execution of 1862,” at the Hillstrom Museum of Art at Gustavus Adolphus College from December 17, 2012 through February 8, 2013. Click here for more information.

Titles for Further Research

David Stannard, American Holocaust: The Conquest of the New World (1992).A well-regarded and relentless account of the genocide of the indigenous people of the Americas as a result of four centuries of colonization and adherence to the concept of American exceptionalism.

Waziyatawin, What Does Justice Look Like? The Struggle for Liberation of Dakota Homeland (2008). A riveting account of “how Minnesotans wrested the land from Dakota people” and proposals for restitution and reparations.

“Dakota 38” (Smooth Feather Productions, 2011). This award-winning film, which can be downloaded from the film’s website, recounts the dream vision of Jim Miller, a Dakota spiritual leader; that dream led to the first commemorative march to Mankato in 2008, which is dramatically presented in the film.

Gwen Westerman and Bruce White, Mni Sota Makoce: The Land of the Dakota (2012). A remarkable new book, providing Dakota history from a Dakota perspective. One reviewer has called it “a new genre of scholarship . . . a geo-historical discourse that dexterously interweaves multiple voices across generations, cultures and places.”

Links: US-Dakota War 1862

Elizabeth Baer is a Professor of English, Holocaust Studies and African Studies at Gustavus Adolphus College in St. Peter, Minnesota. Her new book, The Golem Redux: From Prague to Post-Holocaust Fiction, is available from Wayne State University Press.

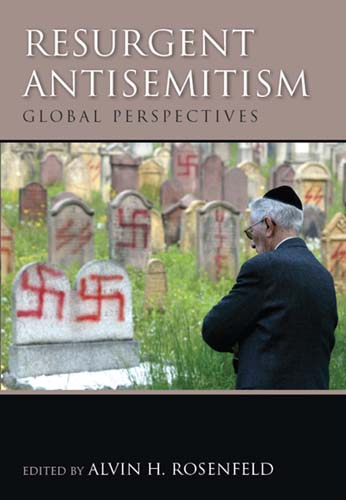

Dating back millennia, antisemitism has been called “the longest hatred.” Thought to be vanquished after the horrors of the Holocaust, in recent decades it has once again become a disturbing presence in many parts of the world. Resurgent Antisemitism presents original research that elucidates the social, intellectual, and ideological roots of the “new” antisemitism and the place it has come to occupy in the public sphere. By exploring the sources, goals, and consequences of today’s antisemitism and its relationship to the past, the book contributes to an understanding of this phenomenon that may help diminish its appeal and mitigate its more harmful effects.

Dating back millennia, antisemitism has been called “the longest hatred.” Thought to be vanquished after the horrors of the Holocaust, in recent decades it has once again become a disturbing presence in many parts of the world. Resurgent Antisemitism presents original research that elucidates the social, intellectual, and ideological roots of the “new” antisemitism and the place it has come to occupy in the public sphere. By exploring the sources, goals, and consequences of today’s antisemitism and its relationship to the past, the book contributes to an understanding of this phenomenon that may help diminish its appeal and mitigate its more harmful effects.

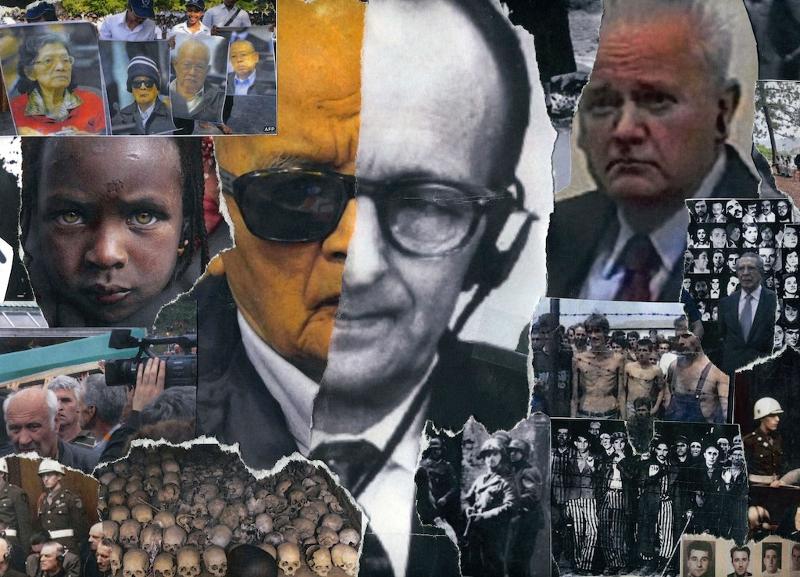

In August 1941, Winston Churchill noted that, while confronted with the atrocities that his intelligence services had discerned in Europe, the world was faced “with a crime without a name.” The second World War marked efforts to define atrocities and mold cultural memory by distinct institutions, such as the media, judiciary and academia; each of which continue to offer their own unique but overlapping framing.

In August 1941, Winston Churchill noted that, while confronted with the atrocities that his intelligence services had discerned in Europe, the world was faced “with a crime without a name.” The second World War marked efforts to define atrocities and mold cultural memory by distinct institutions, such as the media, judiciary and academia; each of which continue to offer their own unique but overlapping framing. The symposium was organized by the Center’s Director, Alejandro Baer, and Professor of Sociology, Joachim Savelsberg, and made possible by the Wexler Special Events fund for Holocaust and Genocide Studies, the Center for Austrian Studies, The Center for German and European Studies and several other centers and departments across the university (for a complete list click

The symposium was organized by the Center’s Director, Alejandro Baer, and Professor of Sociology, Joachim Savelsberg, and made possible by the Wexler Special Events fund for Holocaust and Genocide Studies, the Center for Austrian Studies, The Center for German and European Studies and several other centers and departments across the university (for a complete list click  The afternoon session explored representations of genocide through the lens of law. Specifically, scholars employed historical examinations of the prosecutions of crimes committed during Argentina’s “Dirty War” and the Darfur conflict to inform our normative assessment of those responsible for genocide and crimes against humanity.

The afternoon session explored representations of genocide through the lens of law. Specifically, scholars employed historical examinations of the prosecutions of crimes committed during Argentina’s “Dirty War” and the Darfur conflict to inform our normative assessment of those responsible for genocide and crimes against humanity. Dilemmas, silence, active rescue, and passivity are words often associated with Pius XII. “Critics” emphasize the wartime Pope’s failure to condemn Nazism, while “defenders” maintain that Vatican neutrality facilitated rescue activities by the faithful. This publication, which consists of the oral presentations of scholars gathered at

Dilemmas, silence, active rescue, and passivity are words often associated with Pius XII. “Critics” emphasize the wartime Pope’s failure to condemn Nazism, while “defenders” maintain that Vatican neutrality facilitated rescue activities by the faithful. This publication, which consists of the oral presentations of scholars gathered at  The way people think about the Holocaust is changing. The particular nature of the transformation depends on people’s historical perspectives and how they position themselves and their nation or community vis-à-vis the tragedy. Understandably, European Muslims perceive the Holocaust as less central to their history than do other Europeans.

The way people think about the Holocaust is changing. The particular nature of the transformation depends on people’s historical perspectives and how they position themselves and their nation or community vis-à-vis the tragedy. Understandably, European Muslims perceive the Holocaust as less central to their history than do other Europeans.

On April 19th, 1945, only a few days after American troops had liberated the

On April 19th, 1945, only a few days after American troops had liberated the  It was on this spot, at precisely this time, that the largest mass execution in American history took place one hundred and fifty years ago. Thirty-eight Dakota akicita (warriors) were simultaneously hung by order of Abraham Lincoln as punishment for their part in the Dakota-US War of 1862. That war, which has mistakenly been called the “Sioux Uprising,” lasted for six weeks from August 18 to late September, 1862; it happened for many complicated reasons, one of which was the failure of the US government to deliver the gold, provisions, and food promised by the treaties in which the Dakota signed away thousands of acres of land. The Dakota were starving. Little Crow, who led the akicita into battle, did so against his better judgment. He had been to Washington, DC, and knew the might of the government and the huge number of Euro-American settlers.

It was on this spot, at precisely this time, that the largest mass execution in American history took place one hundred and fifty years ago. Thirty-eight Dakota akicita (warriors) were simultaneously hung by order of Abraham Lincoln as punishment for their part in the Dakota-US War of 1862. That war, which has mistakenly been called the “Sioux Uprising,” lasted for six weeks from August 18 to late September, 1862; it happened for many complicated reasons, one of which was the failure of the US government to deliver the gold, provisions, and food promised by the treaties in which the Dakota signed away thousands of acres of land. The Dakota were starving. Little Crow, who led the akicita into battle, did so against his better judgment. He had been to Washington, DC, and knew the might of the government and the huge number of Euro-American settlers. In 1948 the United Nations passed the Genocide Convention. The international community was now obligated to prevent or halt what had hitherto, in Winston Churchill’s words, been a “crime without a name”, and to punish the perpetrators. Since then, however, genocide has recurred repeatedly. Millions of people have been murdered by sovereign nation states, confident in their ability to act with impunity within their own borders.

In 1948 the United Nations passed the Genocide Convention. The international community was now obligated to prevent or halt what had hitherto, in Winston Churchill’s words, been a “crime without a name”, and to punish the perpetrators. Since then, however, genocide has recurred repeatedly. Millions of people have been murdered by sovereign nation states, confident in their ability to act with impunity within their own borders.