*Editors Note: This piece was originally posted by MinnPost.

During Pride Month, the University of Minnesota Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies grapples with the complicated legacy of remembering and memorializing LGBTQIA+ individuals, who for too long remained absent from collective memory of the Holocaust and other acts of genocide or mass violence. As I worked to compile resources for K-12 and university educators teaching about these topics, certain patterns became clear. It is true that homosexual men are the subjects of existing Holocaust historiography, as men engaging in homosexuality were sent to concentration camps in large numbers, and they faced incredibly brutal treatment during and after the Nazi period. However, Nazis’ strictly prescribed roles for gender and sexuality also meant that others fell victim to state violence and persecution and post-war, queerphobic, collective amnesia.

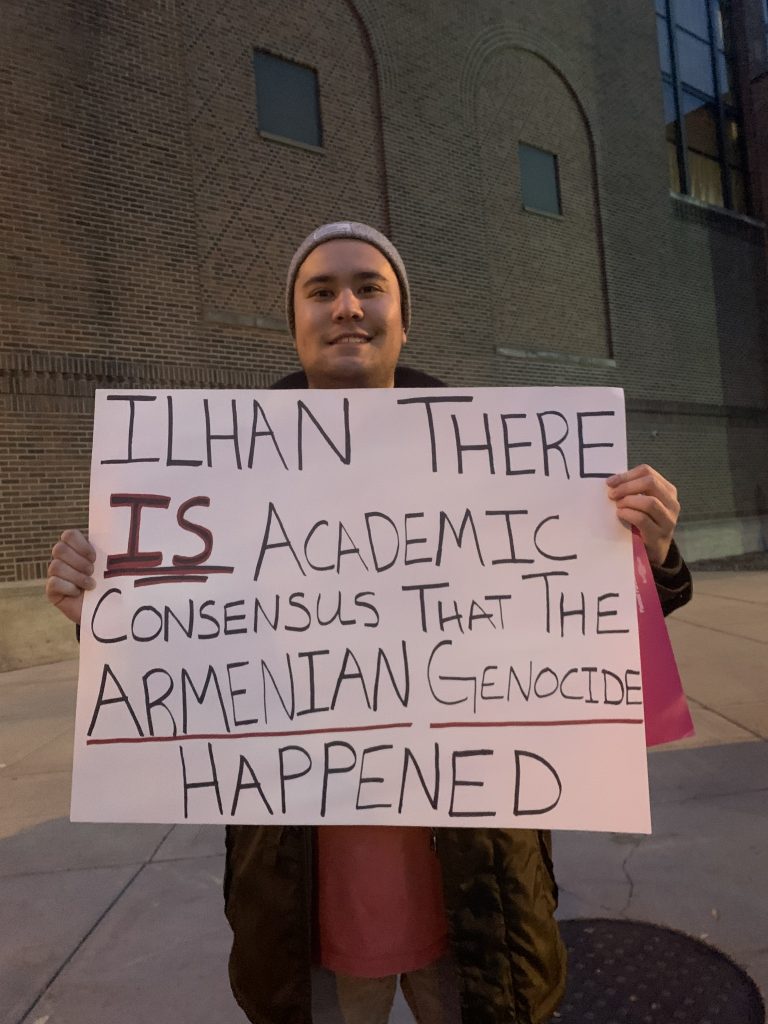

Furthermore, Holocaust testimonies rarely mention homosexuality in a positive light, which continues to lead to additional elisions among the organizations and institutions tasked with preserving this past. If queerphobia continues to serve as a means of ostracization and exclusion, queering the past and histories of genocide is an ongoing and a multidirectional task. Queer activists, students, and scholars past and present self-critically continue to recover, complicate, and amend certain orthodoxies when studying genocide and mass violence; the resonances across time and space among various groups are profound. Gender and sexuality remain (among many topics) understudied within genocide studies more broadly. Where, then, does a larger, more inclusive understanding of the past enter into K-12 and university curricula? With a discerning eye, the past begins to circulate anew, and more inclusive histories emerge in unexpected ways.

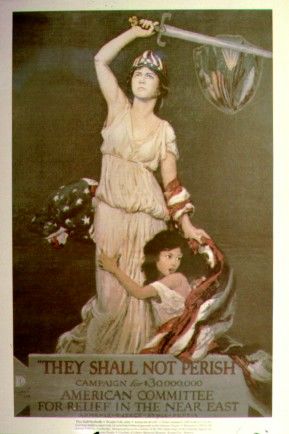

As I made my way through Sarah Schulman’s extraordinary “Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP, 1987-1993,” subtle (and not-so-subtle) reverberations with both our present moment and our collective past became apparent. While we are globally still battling the COVID-19 pandemic, the story of AIDS activism certainly touches on another recent example of governments’ in/action, public backlash and ignorance around deadly diseases, and the disparities around race, gender, and socioeconomics in health care around the world. But within this book, one that critics have coined “part sociology, part oral history, part memoir, part call to arms,” the resulting story of AIDS activism also illuminates other focal points beyond the lack of government intervention and public apathy; Schulman also stresses the central role of imagery and words (i.e., symbolism) from the past for ACT UP’s (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power’s) messaging.

The importance of (rehashed) symbols and slogans for political activism is nothing new, and it was not what solely made ACT UP a revolutionary protest movement. Nevertheless, in a post-Stonewall world, ACT UP consisted of many prominent artists and advertisers in its ranks, and they created polished campaigns that effectively circulated memorable language and images to combat the lack of action around HIV/AIDS. Furthermore, many of the activists themselves were HIV+, and either queer, from marginalized groups, or a combination of intersectional identities.

It was ACT UP that spurred public awareness surrounding the persecution of sexual minorities and the policing of gender under the Nazis (at least in the Anglophone world) post-Stonewall. Many of the movement’s activists were also Jewish, and often had familial ties to the Holocaust. One such intersection of queer and Jewish history occurred at a protest at the World Trade Center. ACT UP activists dressed as office workers, wore masks that said FACELESS BUREAUCRATS, and carried lunch board signs that read, “IT’S NOT MY FAULT, I DIDN’T KNOW ANYTHING ABOUT IT. NOBODY TOLD ME ABOUT THE OVENS.” A common defense among Nazi war criminals, collaborators and ordinary citizens alike, this common adage satirically used by ACT UP exposed the societal complicity in mass death of PWAs (People with AIDS). When the response from public officials ranged from apathy to scapegoating, it did not take much to link these non-responses to other iterations of state-sponsored violence and public apathy.

The success of ACT UP’s images lay in a larger politicization of aesthetics that reverberated for years. One of ACT UP’s most successful campaigns was Silence = Death / Silencio=Muerte, which utilized the pink triangle used in Nazi concentration camps to identify homosexuals. Instead of the triangle being upside down (the way in which it was used by the Nazis), the triangle was placed right-side up. This not only subverted and departed from the Nazi usage, it also effectively conjured up the memory of past persecution of sexual minorities without reducing minoritized groups to victimization.

The imagery was so successful that the ways in which these mediated images and symbols took on a life of their own. Silence = Death circulated within the Klezmer revival movement, where many of its musicians and activists were queer and/or Jewish, and were revitalizing Yiddish language, music, and culture after its decimation in Eastern Europe during the Holocaust. The most notable example was with the Klezmatics, who used the Yiddish translation, שװײַגן איז טױט (transliteration: Shvaygn iz toyt) for their debut album in 1989. On the album cover, the text appears in both Yiddish orthography and transliteration, surrounding a photo of the band members, at least one of whom, Lorin Sklamberg (who identifies as gay) is wearing a pink triangle.

Echoes of the past appear in unexpected places, not always directly connected to the acts of mass violence in question, but surface in a myriad of ways within a larger culture and are equally worthy of critical study and examination. How does Yiddish music in the late 20th century not only grapple with the genocide of Eastern European Jewry, but how can it place itself in dialogue with a larger community of cultural and political activists? How can the memory of genocide serve not to re/traumatize, but to instead work through the myriad ways targeted groups survive mass violence, even if justice is never served on their behalf? As a gay Yiddishist myself, who teaches university and community-education students in multiple languages (including English, German, and Yiddish), these are central questions when studying these topics.

These two examples of ACT UP that incorporate Holocaust memory also demonstrate that queering history in this way (and especially the histories of the Holocaust and other acts of genocide and mass vioence) would not be possible today without the protest and political movements that made LGBTQIA+ visiblity possible. Knowing that a genocide took place is not enough. Yes, engaging with culture(s) destroyed by fascism in a nuanced way is a next step, but so is learning of cultural revival and continuation in spite of a violent past. The same approach holds true for the myriad of queer histories we are obligated to study and complicate. It is an approach that serves as a reminder: Singular histories fail to grapple with the events in question, as the events resonate differently across time, space, and among affected groups.

Educational resources for Pride Month:

K-12 Resources

From USHMM :

- Gay Men under the Nazi Regime

- Gays and Lesbians – A bibliography (based on the museum’s library holdings)

A recent interview with Professor Alisa Solomon on Eve Adams, a radical queer Jewish feminist, who was deported by the United States to Poland and later murdered by the Nazis. A new book about her can be found here:

Meyer Weinshel is a Ph.D. candidate in Germanic studies at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities, where he is the educational outreach and special collections coordinator for the UMN Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies. In addition to being an instructor of German studies, he has also taught Yiddish coursework with Minneapolis-based Jewish Community Action and at the Ohio State University.