The following describes how I have explored settler colonialism theory with my secondary social studies students. Like many of my students in a rural south-central Wisconsin community, I am White and from a working-class background. I share my students’ struggles in understanding our place and identities within the larger landscape of U.S. society. We’ve found that settler colonialism theory helps to complicate and nuance our understanding of the history and present realities of the United States.

Setting the Stage

Before our in-class discussion, I typically assign two TED Talks for students to watch: Aaron Huey’s 2010 “America’s Native Prisoners of War” and Bryan Stevenson’s 2012 “We Need to Talk About Injustice.” Both present hard truths about the histories and legacies of the genocide and dispossession of Indigenous peoples and the enslavement and mass incarceration of African Americans. Though increasingly common, the realities of Indigenous genocide and African American enslavement, which are called the United States’ “first sins,” are rarely discussed in social studies curricula and classrooms as part of the same overarching structure of settler colonialism.

We begin class by discussing the TED Talks. Though my students are sophomores in high school, most have had few opportunities throughout their formal schooling to discuss the issues raised in either talk. Initially, the issues discussed by Huey and Stevenson seem far away or part of some other America. Indeed, the August 2020 police shooting of Jacob Blake, the responding uprisings, and the co-occurring white nationalist violence in Kenosha, Wisconsin (60 miles away) highlighted the sobering reality of racism in Wisconsin. Yet, these went unmentioned and seemingly unnoticed by students at the start of this school year. These talks provide accessible entry points for class discussions. Note: Huey’s talk demands additional scrutiny. As a white photojournalist, his images from the Pine Ridge Reservation that accompany the talk – images that appeared in a 2012 National Geographic cover story – could perpetuate the (settler) colonial gaze.

Drawing Indians

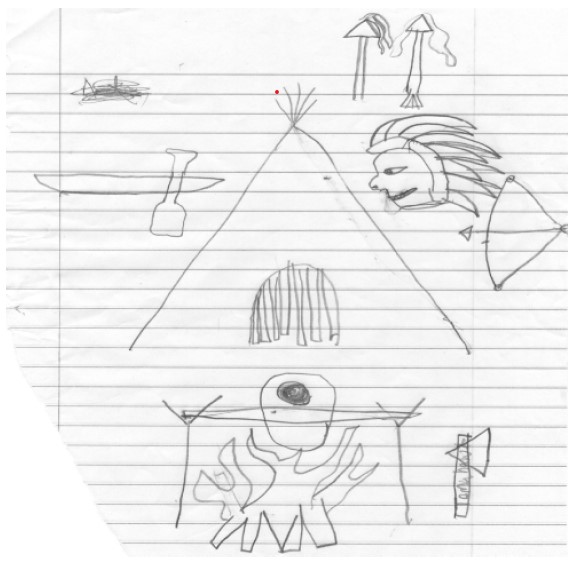

Next, borrowing a prompt from Patrick LeBeau (Cheyenne River Sioux), I instruct students to “draw what you know about Indians” on a sheet of notebook paper. Though initially uncomfortable with the prompt, students soon begin filling their sheets with images. Similar to what LeBeau has found, students’ drawings invariably include teepees, tomahawks, and feathered headdresses – the stereotypical trappings of nineteenth-century Plains Indians. These are reflected in schoolwork from my own childhood, as well (see image below). Asking students to reflect on why these are the common images they hold of American Indians (images that are still prevalent in advertising, sports, and education) pushes non-Indigenous students to reckon with how they view American Indians.

Defining Settler Colonialism Theory

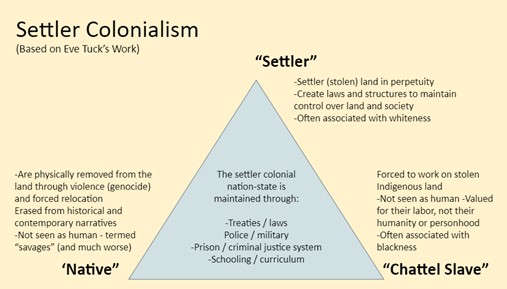

Next we examine Eve Tuck (Unangax̂) and K. Wayne Yang’s settler-native-slave triad, which provides a framework for understanding power relations within settler colonial society regarding land. Settler colonialism is a distinct type of colonialism in which non-Indigenous settlers remove and then replace Indigenous inhabitants on the land, occupying the land in perpetuity. Simultaneously, Africans and African Americans are enslaved to work the land.

Within the triad, settlers occupy stolen Indigenous land, creating structures to ensure their continued dominance over society and land. The native continues to be removed from the land and erased within historical and contemporary narratives, while the chattel slave is restricted from owning land, disenfranchised, and valued exclusively for their labor. The prison-industrial complex represents a continuation of enslavement in U.S. society. Thus, Patrick Wolfe wrote that settler colonialism is a “structure not an event,” infused with a genocidal “logic of elimination.” While students might initially view the settler-native-slave triad as corresponding to identities, la paperson wrote that these are not identities, but rather technologies of the settler nation-state.

“Therefore, the ‘settler’ is not an identity, it is an idealized juridical space of exceptional rights granted to normative settler citizens.”

Thus, racialization and the racial categories of Whiteness and Blackness serve as organizing logics, or tools for maintaining settler colonialism.

Returning to the TED Talks, students reflect on the following quotes through a settler colonial lens:

- “More than 90 percent of the population [on Pine Ridge Reservation] lives below the federal poverty line […] The life expectancy for men is between 46 and 48 years old — roughly the same as in Afghanistan and Somalia” (Huey).

- “In urban communities across this country — Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington — 50 to 60 percent of all young men of color are in jail or prison or on probation or parole” (Stevenson).

Viewed through the lens of settler colonialism, the structural issues described by Huey and Stevenson are clarified and brought into relationship.

Settler Colonial Imagery in the Settler Colonial Imaginary

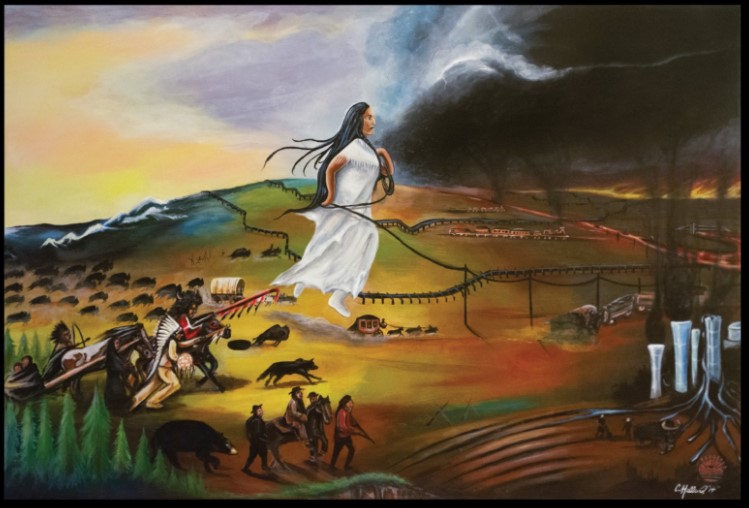

Next, we turn our attention to John Gast’s 1872 painting: American Progress. In the painting, Columbia, adorned with the star of empire, floats across the American landscape. Stringing a telegraph wire, she ushers in settlement via Conestoga wagons, stagecoaches, and railroads. Bringing the light of civilization, she drives out darkness along with buffalo and Indigenous peoples. The imagery of the piece is not subtle, and students have little difficulty decoding the painting using a settler colonial lens.

When considering the book in Columbia’s arms, most students reason she holds the Bible. However, zooming in, they see it is a school book. This revelation leads us to discuss how schools and curriculum function as mechanisms to sustain and perpetuate settler colonialism. Dolores Calderon has analyzed social studies curricula as examples of “settler grammar,” or those “discursive logics that maintain settler colonial ideologies.”

Unsettling Local Erasures

Clinton, Wisconsin, the rural community where I teach, like all settler communities, has a long history and collective memory of misrepresenting or erasing Indigenous peoples. A log cabin stands in town as a “visible reminder of the sacrifices made by early pioneers as they settled this area.” Yet, the many Indigenous communities that have called this land home are nowhere mentioned. The practice of memorializing first settlers through monuments while simultaneously writing Indigenous peoples out of existence is what Jean O’Brien (White Earth Ojibwe) referred to as “firsting and lasting.” A 1987 volume of local history stated: “There seems to be no record of any permanent Indian settlement located at Clinton before the coming of the Whiteman.” Discussing these local erasures brings the lessons of settler colonialism home for students. We follow these discussions with learning about land acknowledgments, which are more common in Canada or U.S. higher education, before drafting our own statement.

Reflections on “Settler Fragility”

Discussions of settler colonialism are not easy for most non-Indigenous students, many of whom can trace their family histories to the founding of this close-knit farming community. It is not uncommon for male students to express frustration or anger when confronting local histories and legacies of violence, dispossession, and continued erasure. Students sometimes crumple their drawings and otherwise disrupt class discussions or put their heads down on their desks and disengage. It is not uncommon for female students, seeking to comfort their agitated peers, to become defensive and seek to excuse past and contemporary settler violence. Settler colonialism is heavily steeped in heteropatriarchal social norms. Such behaviors signal what Dina Gilio-Whitaker (Colville Confederated Tribes) called “settler fragility,” or the “the inability to talk about unearned privilege—in this case, the privilege of living on lands that were taken in the name of democracy through profound violence and injustice.”

Beyond Settler Colonialism

J. Kēhaulani Kauanui (Kanaka Maoli) reminds us that taking up settler colonialism, though important, cannot replace the need for Indigenous (as well as other BIPOC) presence in the curricula, classroom, and community. While settler colonialism theory helps students recognize the logics that govern schooling and society, this lesson is only part of my and my students’ efforts to unsettle traditional social studies education.

George Dalbo is a high school social studies teacher and Ph.D. candidate in Curriculum and Instruction and Social Studies Education at the University of Minnesota. His research interests include Holocaust, genocide, and human rights education in K-12 curricula and classrooms.

Comments 3

Paul Xxx — February 1, 2021

Have studies been done on the degree of war, displacement and murder of Indians by other Indians? If so how do they compare that done by white settlers? Jared Diamond said that a person stood a better chance of survival in Poland during WWII than in a new guinea village.

Anna G — September 10, 2021

@Paul. What does your question have to do with this lesson? The only connection I can see is your own "Settler Fragility" being put on display. Are you asking if the remaining indigenous people are better off after having been dispossessed of their rightful lands? Are you saying they deserved genocide because some indigenous communities had a culture that included war and violence? What really are you trying to say/ask?

Carmen — February 28, 2022

As an undergraduate student who has been trying to grapple with ideas around how we might decolonize outdoor/environmental education I have found your reflection to be incredibly helpful, and I have referred to it on several occasions. Engaging with the above topics on a personal level helps give me hope for the future even as our political/social/environmental situations grow more dismal. It seems to me that Indigenous, Black, Queer (and so many others) led movements and initiatives might prove more suitable than western science and politics. Thanks for engaging in these conversations, and challenging settler colonial structures and systems, and asking your students to do the same!