The CHGS Blog now has a Student Opportunities page! This page will be central location for students to find Calls for Papers, Conference Announcements, Funding Opportunities, and other resources.

Have anything you’d like to add?

Calls for Papers, Conferences, Workshops, Seminars

Deadline: October 15, 2016 – Workshop on Localization of videotaped testimonies of victims of National Socialism in educational programs. Workshop funded by the Foundation “Remembrance, Responsibility and Future” (EVZ) in preparation of the next volume of the series “Education with Testimonies.” Vienna, January 9-11 2017

Deadline: October 16, 2016 – Sustainability and Transformation: International Conference on Europeanists; University of Glasgow, UK, July 12-14 2017

Deadline: October 30, 2016 – Stepping Back in Time. Living History and Other Performative Approaches to History in Central and Southeastern Europe; German Historical Institute, Warsaw, February 20–21 2017

Application Deadline: November 1, 2016 – 2017 Jack and Anita Hess Faculty Seminar: Gender and Sexuality in the Holocaust; USHMM, Washington DC, January 9-13 2017

Deadline: December 15, 2016 – International Association of Genocide Scholars Conference; University of Queensland, Brisbane, July 9-13, 2017

Deadline: December 15, 2016 – Media and History: Crime, Violence, and Justice; International Association for Media and History, Paris, July 10-13 2017

Currently Accepting Proposals – Thinking Through the Future of Memory; Council for European Studies, Amsterdam, December 3-4 2016

Dealing with the Past in Northern Ireland: the Victims’ Perspective; Transitional Justice Institute, Ulster University, Jordanstown Campus, October 19, 2016

5th Annual Symposium on Women and Genocide in the 21st Century: The Case of Darfur; Washington DC, October 21-22 2016

Oral History in the Age of Change: Social Contexts, Political Importance, Public Challenges; Kharkiv, Ukraine, December 1-2 2016

International Workshop: Colors of Blood, Semantics of Race; Casa de Velázquez, Madrid, December 15-16 2016

Museums and Their Publics at Sites of Conflicted History; POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews, Warsaw, March 13-15 2017

The Holocaust and History: The Work and Legacy of David Cesarani; University of London, London, April 3-4 2017

Emerging Expertise Conference: Holding Accountability Accountable; Clark University, Massachusetts, April 6-9 2017

Traces and Memories of the Cambodian Genocide: Tuol Sleng in testimony, literature, and media representations; University of Utrecht, The Netherlands, July 6-9 2017

Calls for Journal Submissions

Deadline for second issue: December 15, 2016 – Antisemitism Studies; Indiana University Press

Deadline: July 1, 2017 – Transitional Justice from the Margins: Intersections of Identities, Power and Human Rights; International Journal for Transitional Justice, Oxford University Press

Human Remains and Violence: An Interdisciplinary Journal; Manchester University Press

Working Paper (WP) Series; Historical Dialogues, Justice, and Memory Network

IAGS Emerging Scholar Mentorship Program

IAGS is pleased to announce a mentor program for emerging scholars. In its early stages, the mentor program will focus on assisting emerging scholars (i.e., students in graduate [M.A. and Ph.D.] programs who intend to work in genocide studies; post-doctoral researchers; unwaged Ph.Ds, and recently-graduated scholars who are within the first three years of their first professional position.) with advice on preparing a specific piece of work for publication.

The manuscript in question should be of regular journal length and at a stage where it is very near ready for publication – manuscripts that are underdeveloped or in a very rough state may be denied access to the mentoring program until they are revised. IAGS IS seeking the following:

- Volunteers among the group of established scholars who are willing to work with an emerging scholar in readying a journal article or book chapter for publication. Please send us your name, contact information, areas of expertise, and the languages you are able to work in. You will not be asked to work with more than one emerging scholar per year, unless you specifically state your willingness to do so. If you receive a manuscript that you feel is not yet ready for mentoring, you may request it be returned to the emerging scholar for further revision

- Emerging scholars who would like advice from an established scholar to help ready a journal article or book chapter for publication. Along with your name and contact information, please send an abstract for the specific piece for which you would like to be mentored and the language in which you would like to mentored. We will do our best to accommodate your request, but we are dependent on the availability of a suitable mentor.

- Genocide Studies and Prevention will also refer journal submissions to this program when they receive articles that show promise, but require further polishing before being sent off to peer review. Publication in Genocide Studies and Prevention is not guaranteed through this program. This is a volunteer-based program solely designed to build helping networks between established and emerging IAGS scholars – it is not available to non-members.

Please send all information to Andrew Woolford, IAGS President awoolford@genocidescholars.org

Funding Opportunities

We are pleased to offer HGMV graduate students funding support for travel to present their research at academic conferences, which includes an exciting new partnership with the UMN Libraries:

CHGS / HRP travel awards funded by the Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies and the Human Rights Program

Library Archives travel awards: the Kautz Family YMCA Archives HGMV Graduate Award, and the IHRC Archives HGMV Graduate Award

Funding for both types of awards will be provided to graduate students in the form of reimbursement for travel costs and registration fees for conferences, symposia, workshops, and meetings where they will present their work.

Topics must be relevant to the Holocaust, genocide, mass violence and other systemic human rights violations. Applications accepted on a rolling basis, first consideration will be given to those students who have presented or are scheduled to present their work in the HGMV workshop.

Library awards require prior consultation with an archivist, and incorporation of archive research in the paper. Archivists are always available for consult via ihrca@umn.edu and ymcaarch@umn.edu.

Please find additional information here.

Bernard and Fern Badzin Graduate Fellowship in Holocaust and Genocide Studies

The University of Minnesota Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies and the Department of History invite applications from current doctoral students in the UMN College of Liberal Arts for the Bernard and Fern Badzin Graduate Fellowship in Holocaust and Genocide Studies. The Badzin Fellowship will pay a stipend of $18,000, the cost of tuition and health insurance, and $1,000 toward the mandatory graduate student fees. Calls for applications usually posted the beginning of Spring Semester.

Eligibility: An applicant must be a current student in a Ph.D. program in the College of Liberal Arts, currently enrolled in the first, second, third, or fourth year of study, and have a doctoral dissertation project in Holocaust and/or genocide studies. The fellowship will be awarded on the basis of the quality and scholarly potential of the dissertation project, the applicant’s quality of performance in the graduate program, and the applicant’s general scholarly promise.

Please find additional information here.

The Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies awards fellowships on a competitive basis to support significant research and writing about the Holocaust. The specific fellowship and the length of the award are at the Mandel Center’s discretion. Stipends range up to $3,700 per month.

The application deadline is November 15, 2016 for the academic year of 2017-2018.

Please find additional information here.

The Saul Kagan Fellowship in Advanced Shoah Studies offers a limited number of fellowships for Ph.D and postdoctoral candidates conducting research on the Holocaust. A Kagan Fellowship award is a maximum of $20,000.

The application deadline is January 3, 2017 for the academic year of 2017-2018.

Please find additional information here.

The Geneva Center for Security Policy and its Geopolitics and Global Futures Programme established a Prize for Innovation in Global Security in order to recognize deserving individuals or organizations that have an innovative approach to addressing international security challenges. The prize is designed to reach across all relevant disciplines and fields. It seeks to reward the most inspiring, innovative and ground-breaking contribution of the year, whether this comes in the form of an initiative, invention, research publication, or organization.

Please find additional information here.

What did people hear about Kristallnacht outside of Germany in 1938 from governments and media sources? How did governments and ordinary people respond to the plight of the Jewish community there? How have lives been affected by Kristallnacht in the seventy years since its occurrence? This interdisciplinary study of erasure and enshrinement seeks to answer these questions, exploring issues of memory and forgetting (in both the material and symbolic sense), and how the meaning of Kristallnacht has been altered by various actors since 1938.

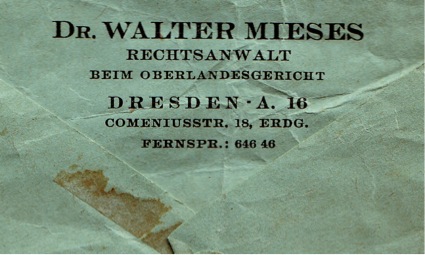

What did people hear about Kristallnacht outside of Germany in 1938 from governments and media sources? How did governments and ordinary people respond to the plight of the Jewish community there? How have lives been affected by Kristallnacht in the seventy years since its occurrence? This interdisciplinary study of erasure and enshrinement seeks to answer these questions, exploring issues of memory and forgetting (in both the material and symbolic sense), and how the meaning of Kristallnacht has been altered by various actors since 1938. In 1929 he resigned his position in the civil service and became a private attorney, representing clients before the Court of Appeals of the State of Saxony, in Dresden. In April 1933, the National Socialist decree that refused all Jewish judges, public prosecutors, and lawyers access to the courts brought his brilliant career to a halt. In the same year he emigrated to Buenos Aires (Argentina).

In 1929 he resigned his position in the civil service and became a private attorney, representing clients before the Court of Appeals of the State of Saxony, in Dresden. In April 1933, the National Socialist decree that refused all Jewish judges, public prosecutors, and lawyers access to the courts brought his brilliant career to a halt. In the same year he emigrated to Buenos Aires (Argentina).

On March 24, 1944, Nazi occupation forces in Rome killed 335 unarmed civilians in retaliation for a partisan attack the day before.

On March 24, 1944, Nazi occupation forces in Rome killed 335 unarmed civilians in retaliation for a partisan attack the day before.  Falko Schmieder is a DAAD visiting professor at the University of Minnesota and is currently teaching the course “History of the Holocaust.” He has studied Communications, Political Science and Sociology at various German Universities. Since 2005 he has worked as a researcher at the Center for Literary and Cultural Research Berlin. Together with

Falko Schmieder is a DAAD visiting professor at the University of Minnesota and is currently teaching the course “History of the Holocaust.” He has studied Communications, Political Science and Sociology at various German Universities. Since 2005 he has worked as a researcher at the Center for Literary and Cultural Research Berlin. Together with  During the 20th century, the Balkan Peninsula was affected by three major waves of genocides and ethnic cleansings, some of which are still being denied today. In Balkan Genocides Paul Mojzes provides a balanced and detailed account of these events, placing them in their proper historical context and debunking the common misrepresentations and misunderstandings of the genocides themselves.

During the 20th century, the Balkan Peninsula was affected by three major waves of genocides and ethnic cleansings, some of which are still being denied today. In Balkan Genocides Paul Mojzes provides a balanced and detailed account of these events, placing them in their proper historical context and debunking the common misrepresentations and misunderstandings of the genocides themselves. With this in mind, the primary role of the high school history teacher must be to expose students to a study of history that allows for asking serious, difficult questions about serious difficult events. The nature of humankind, the justifiable use of military force, definitions of race, the roots and motivations of stereotypes – these have been with us for centuries, they are ambiguous and moral to their core, and absolutely necessary for human development and progress.

With this in mind, the primary role of the high school history teacher must be to expose students to a study of history that allows for asking serious, difficult questions about serious difficult events. The nature of humankind, the justifiable use of military force, definitions of race, the roots and motivations of stereotypes – these have been with us for centuries, they are ambiguous and moral to their core, and absolutely necessary for human development and progress.