Prof. dr. Sarah Cramsey is the Special Chair for Central European Studies at Leiden University, an Assistant Professor of Judaism & Diaspora Studies and Director of the Austria Centre Leiden. From 2025-2030, she will be the Principal Investigator of “A Century of Care: Invisible Work and Early Childcare in central and eastern Europe, 1905-2004” or CARECENTURY, a project funded by a European Research Council Starting Grant.

On January 27th, 2025, on the occasion of the commemoration of the 80th Anniversary of the Holocaust Remembrance Day, the Center for Austrian Studies and the Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies at the University of Minnesota invited Dr. Sarah Cramsey to give a lecture, titled: “The Other Holocaust: Care, Children and the Jewish Catastrophe”.

In your recent talk on January 27th, you presented the study of caretaking through three distinct case studies. Does your forthcoming book adopt a similar structure?

Yes, in my book there are three chapters that correspond to each of those three case studies – the Warsaw Ghetto, Auschwitz-Birkenau and the Soviet Union during the Second World War –, and that is the heart of the book.

I have a personal and an academic answer to this question. The personal answer is that during the time that I was pregnant with my two kids, one of them during the pandemic, I began to realize that the way that my life had shifted, and the horizon of my consciousness wasn’t necessarily reflected in a lot of the histories that I had read, particularly in the region that I am interested in – the land between Salzburg, Sarajevo and St. Petersburg.

As a historian, whenever you are thrown into a situation, you like to go see what people have written about this situation in past circumstances. And, of course, there is work about the history of childhood, but I was very interested in the conceptual idea of care: how we care for the very young, and I became interested in how this invisible work sustains human life at a very young age.

When you have a child, you confront so many assumptions that people have about how you should be caring for that child: whether or not you should be breastfeeding that child, using the cry-it-out method, sleep training, etc. And this is something that happens differently in different societies, and beyond the care of the baby: governing women’s bodies, what constitutes a good home for the child, what role is the mother supposed to have… And, in a more fundamental level, in terms of the transmission of caretaking knowledge: relying on the knowledge of your relatives and older people as to what to do with the baby. Here you also see a lot of contradictions and assumptions. I became really interested in the contradictions, in the tensions, because it was something that I was living through as I became aware of the historical tensions spiraling out from my own experiences.

And the academic answer?

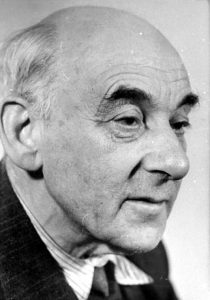

The other side of my answer, a more academic one, stems from my first book, “Uprooting the Diaspora”. In that book I look at changing ideas of Jewish belonging and conceptions of Jewish citizenships in Europe. I looked at an organization that was very important for this narrative, the World Jewish Congress (WJC), and there was a really moving document, a transcript of a meeting from June 8th, 1944. Members of the executive committee had learned that there were systematic trains leaving the occupied (now) Hungary, and towards Auschwitz-Birkenau. They began to realize that not even Hungarian Jews would be safe from the Shoah unfolding in Europe. In this meeting, members gave their honest opinion on the question of whether they should support the return of Jews to Germany after the war. A.L. Kubowitzki, secretary of the WJC and representing Belgian Jewry, gave a speech in response to this question, and he said that his opinion had changed from the last time they talked about this. In his speech, he references his son, he says “I need an answer to bring to my son”.

After I finished the book, I was reading through it and I thought to myself “I wonder what happened to that son, I wonder if I can find him”. I found him, Michael Kubovy, now a retired professor emeritus in psychology at the university of Virginia in Charlottesville. I reached out to him, and he was very receptive, so I planned a visit. And it was then that I realized how much I was missing about A.L. Kubowitzki’s life, about the day to day of this very important diplomat. I knew nothing about the family behind him. His wife, for instance: Michael’s mother, who had been supporting the family during those important years I had researched. So, I started wondering what I knew and did not know about this family that had a very interesting life. Michael knew so many important things about his father and his life, and talking to him let me to see more of the invisibility of the history that I had written. Talking to him answered very different questions than the ones I had initially asked, ones that really highlighted the nuts and bolts of life, which led me to become interested in this taboo subject of early childhood caretaking, which is often invisible to the written record.

What do you mean when you say caretaking is universal, yet invisible to the eye and to the written record?

I see this as a timeless historical question, and these are the best historical questions to write a book about. A question that can relate to any time period or any group of people. Anyone who has ever spent more than a minute with a baby knows that, at some point, you look at that baby and you think: “What do I do to keep you alive? How do I get you to be happy and stop crying?” That is a very universal human question dating back to Neanderthals, and even in the animal world. So, this question of care is universal, beyond human existence, but also historically contingent. And I thought about this puzzle, this question of “How do you tell the history of something that appears timeless but also constantly changing”.

The overall invisibility of caretaking in the written record became to me an important methodological question: how do you write a history of the first two years of being alive, when you often have no direct documents from the people involved in that relationship? Thinking about this dirty, constant, relentless work from the end of the time in the womb and the early years of a child brought me to realize how much I didn’t know about it, and how sparse the available documentation seems to be. That spanned me in a different direction to try to figure out how can I find documents to make this invisible work visible.

This goes back to what you mentioned earlier, about how asking new questions about the importance of this invisible work leads us to uncover very different histories. Other than exploring this question in your upcoming book about early childhood caretaking during the Holocaust, you are also leading a broader project funded by the European Research Council, “A Century of Care. Invisible Work and Early Childcare in central and eastern Europe, 1905-2004”. Can you talk more about this project, and about what sources will you be examining to make this invisible work visible?

This project will allow me to have a very long chronology and a very large geographic space – I will be looking at the farthest extent of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the states that have been called its successor states: Austria, Czechoslovakia, Romania, Hungary, Yugoslavia and Poland. This is already a huge undertaking, to look at a hundred years of childcare, across such a vast territory. The way that I try to make this work visible is by using unique voices, spaces, and things. In the presentation I gave, for instance, I talked about the French Polish Jewish artist David Olère, who after the war, starts sketching about his work in the Sonderkommando working in the gas chambers. If you look through his paintings, you see many depictions of children with their mothers. This made me wonder if I could examine other Sonderkommando testimonies to see if they were also noticing the presence of young children, pregnant women, and what care looked like in those situations.

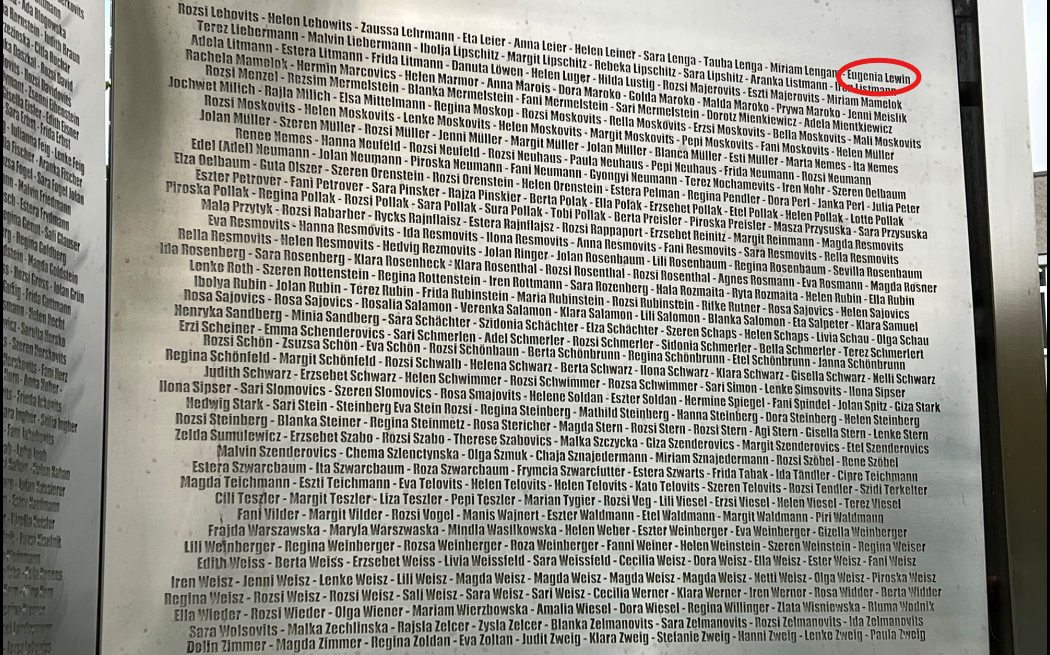

Because of these paintings we are also able to conceptualize certain spaces where care continued to happen and allows us to look at the materiality of care because we see things that people had brought along on these long journeys when thinking about providing for their children. For instance, photographs of the arrival of people at a concentration camp is also a valuable source to examine caretaking relationships because we can see if there are people holding a baby, if they hand them off to other people, what are they carrying with them, are the children crying, what are they wearing, etc. By looking at these documents you realize that care and care networks become an important part of how the final solution became possible, because so many women -not necessarily only mothers, but often mothers- would not leave their children. By having young children with them, they would often be considered unfit to work. Care becomes an important weapon to exterminate young mothers, which is something important to think about, because it also helps us think more deeply about the role of the Jewish child in Nazi ideology, which is the focus of another chapter in my book.

Another space I look at are playgrounds. For instance, in the city of Budapest, in 1907, there was one playground. Of course, children play in many other places, but there was one official playground. By the 1970’s, there’s 1,400. This is a complete revolution in the way that children play and the way that a new parent experiences the city. We can ask so many fascinating questions: Who is designing this playground? How did they pick the slide? It allows us to ask interesting questions about the different spaces where caretaking takes place.

On the other hand, I will be exploring the materiality of early childcare: baby formula, infant bottles, infant clothes, objects that people used to help infants get certain skills. I am interested in the materiality of care, and it is one way that I can make things more visible.

These are some of the ways that I hope to use voices, spaces and things to identify this invisible work.

Tibisay Navarro-Mana is a PhD Candidate in the History Department and Research Assistant at the Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies. Her research focuses on the politics of historical memory in Spain after the Spanish Civil War and the Francoist Regime, looking particularly at the intersections between memory, media and propaganda by analyzing public media representations of the Francoist Regime’s welfare system.