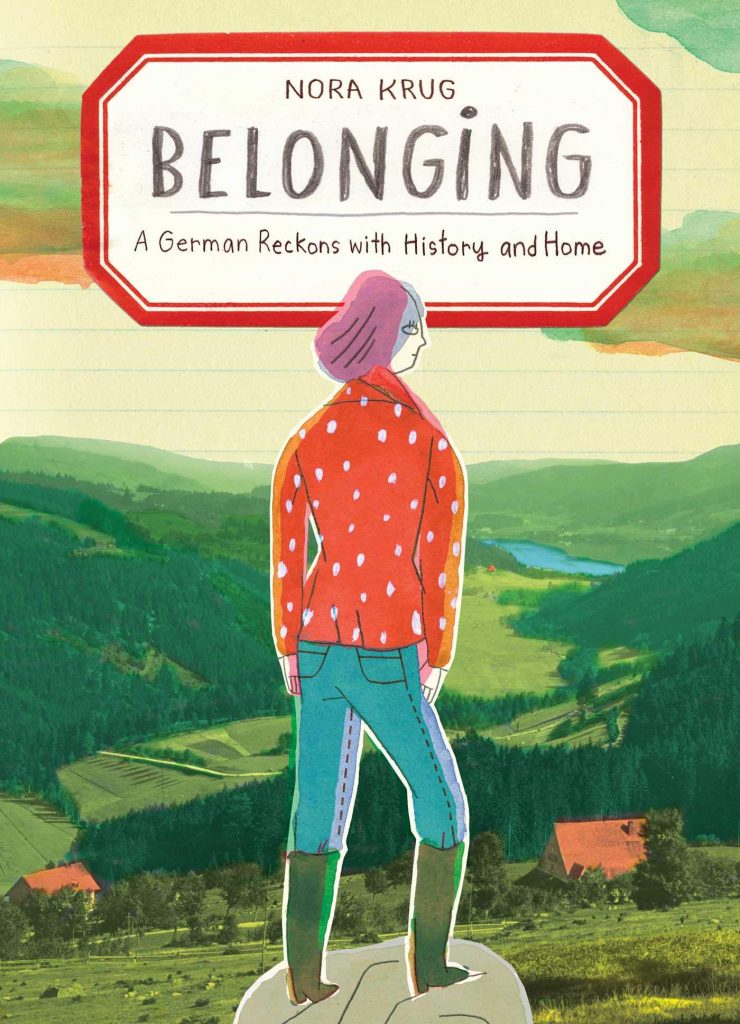

Nora Krug is a German-American author and illustrator. Her 2018 visual memoir Belonging: A German Reckons with History and Home about WWII and her own German family history, has won numerous awards and has been translated into several languages. Krug is an Associate Professor of Illustration at the Parsons School of Design in New York City. She spoke at the University of Minnesota in February 2020.

George Dalbo: You have said that it took leaving Germany for you to get to a place where you could conceive of writing your graphic memoir. Could you expand on this? Additionally, is there something about settling in the United States, your current personal or professional situation, or the present political or social climate that also influenced your decision to write the book?

Nora Krug: Many different factors contributed to my writing this book. One of the strongest was definitely that I left Germany. This is probably an experience that many people have had; when you leave your home, and you find yourself surrounded by people who are not from your cultural context, you suddenly begin to realize how deeply rooted you are in your own culture, and you are simultaneously confronted with your own culture in a much different way than if you had never left. Of course, growing up in Germany in my generation, we learned so much about the Second World War and the atrocities that were committed, but we learned about it collectively. When you remove yourself as an individual from that context, you are suddenly forced to confront the subjects on an individual rather than a collective level because you are approached about them as an individual by the people around you. This, at least, has been my experience. Also, settling in New York City, which traditionally had been the major port of entry for refugees from the war, I was much more aware of the effect that my cultural heritage could have on my neighbors and my friends, many of whom are Jewish. That certainly contributed to my thinking about the book, as well. Had I moved to Seattle or the Midwest, I probably would not have felt the same confrontations.

In the United States, one often hears that Germany has done such a good job confronting their own difficult past with World War Two and the Holocaust, especially. Do you think that this is the case? In your opinion, what have been some of the gaps in the way Germany has approached its difficult past?

I think Germany has done a very good job when it comes to remembering, memorializing, and collectively making public commitments to taking on responsibility so that such things will never happen again. You can see this, despite the recent far-right-wing extremism in Germany, in everyday German life and in German politics, as well. People go to the barricades very quickly when such developments happen. Just this week, you saw an example of this; the public outcry when the Conservative party [Christian Democratic Union] basically collaborated with Alternative für Deutschland. It was very satisfying to see how quickly people reacted to that in a negative way, a critical way. Where we still have a lot of work to do is on an individual level. I think that a lot of the experiences that we had, as I mentioned before, were collective and institutional. This is tremendously important; if institutions do not recognize and acknowledge the mistakes that a country has made, that is a huge problem for the country. I’m not trying to diminish the collective aspect, but the individual effort is as important because if you only memorialize collectively, you avoid the personal confrontation, and this can lead to a sense of tiredness about having to address the subject as a group, a feeling of being burdened by that task, which, I think, many Germans feel. If you do not approach the subject on an individual level, you can not take agency, individual agency. That is what I tried to do with my book, to think about investigating my own family, because I perceived it as something freeing. It freed me from this paralysis of feeling guilty but not knowing what to do about it. I have not overcome my feelings of guilt, but I have addressed them on an individual level, which made me feel like I had some agency as an artist and as a writer to talk over these things. It made me feel that I had a more constructive way of dealing with the guilt.

For the graphic memoir, you rely on several sources to reconstruct your family history, such as local and national archives, family documents, flea market finds, and personal reflections. In many cases, such as with your grandparents, who had passed away, you were unable to have conversations with family members about their experiences during World War Two. How does this shape the narrative? In what ways does this make your work similar or dissimilar to other works in this genre of Vergangenheitsbewältigung [“working through the past”] memoirs?

I think it was similar for most Germans; the grandparent’s generation did not talk much about these things, and, because of that, our parent’s generation did not know much about their experiences. It was not so much that our parents did not want to talk about these things and deprive us of these stories; they themselves had no information because their parents did not talk about their experiences. Older generations also did not have access to all of the technological tools and the research documents available today. Actually, they could not have gone beyond conversations with their parents or grandparents. In other words, the internet did not exist, and certain documents were not made open to the public at that point, so, even if my parents had wanted to go further with trying to find out about the past, they could not have accessed the same materials that I was able to access. I think my generation has many more entry points into this kind of research, and with my book, I really tried to think of any way in which I could get information. The archival research was just one type of research. I did also have conversations with people who were still alive and who knew my family in person. I conducted interviews with people who took the place of my grandparents. Also, there are the flea market objects and items, which, to me, provided both a collective and personal entry point into that period because they represent objects that were used and collected by many Germans. Such research allowed me to represent a collective German point of view, not necessarily a family member’s point of view from my family. At the same time, it is also a highly individual view; I was able to connect to these objects on an individual level even though they belonged to people I did not know at all.

Who do you see as the audience for the book? Especially as the memoir is released in translation, how do you imagine non-German audiences are connecting with the work?

Every country has its own perspective, experience, and narrative surrounding World War Two. I think that we all construct narratives about traumas retroactively. These narratives say something about our culture, and, for Germans, that narrative is obviously and completely steeped in guilt, as well as neglecting to talk or writing about German loss during the war. The Germans are incapable of really considering what the trauma of the war and the Holocaust did to them; certainly, we brought this trauma on ourselves, but it is still a trauma that we are trying to deal with to this day. I think that it is difficult for some Germans to admit this because it would put us in a position of victimhood. In the United States, there is a very different narrative, which is one of the United States as the liberator, and there is sometimes very little nuance given to different narratives that existed on the American side as well. I have noticed that when I am traveling with the book in the countries where it has come out that the responses I receive and the questions I am asked are informed by these different cultural perspectives. In Germany, the book has probably found its biggest audience, which is because a lot of Germans can identify with this story and this viewpoint, and many Germans have not tried to write about their own personal narrative. They really have not been able to figure out how to do that. Again, maybe this is because talking about one’s own losses is considered inappropriate. To some Germans, my book seems like an entry point for conducting this kind of family research. Indeed, I’m often asked by German audiences how they can begin to do such research. For many people, both German and non-German, there is little consideration that there could be a German viewpoint that is not just the Nazi perspective. I think it is very important to consider these other views because we can learn so much from them. If we try to understand how people came to think this way, we can prevent these things from happening again in the future. I think it is very important to get inside the more intimate, nuanced German war experience. What has been really satisfying when traveling with the book has been that people in all the countries I’ve been to so far have been able to translate the idea of responsibility for a national past to their own country’s history, whether this was a Canadian audience talking about First Nations people and the lack of work that has been done around that or the history of slavery in the United States. In France, journalists talked to me about the importance of actually discussing the French collaboration with Germany which has been underemphasized there because of a focus on the resistance, The memoir has been understood on a universal level, which is the best thing that could have happened, because it is not really about my family or about Germany, but it is about something more universal than that.

In addition to illustration, you use many photographs, both personal and not, in the memoir. Could you speak a little bit about your choice to use photographs and some of the ethical considerations you weighed in using them?

I’m somebody who really believes that it is our responsibility not to look away. Of course, if there is an exploitative aspect to using the photographs, then that is wrong. I think that if you can use images sensitively, you have to show them because we owe it to the people who perished to not look away. I think we owe it to them to confront ourselves with their hardship. That is not only true for World War Two and the Holocaust, but it is also true for things that are going on right now. I Think about how little we know about the conflict in Yemen and how rarely we actually see photographs of injured children, though they are being attacked on a daily basis. I think that once we see these things, we feel much more compassionate. In the course of writing the book, I thought very carefully about how to use images. One of my biggest goals was not to create a sense of false sympathy for the Germans or a sense of sentimentality, which images can very quickly do if they are used in the wrong way. In several images in the book, you see dead bodies in the background, but I decided that I wanted to focus on the German facial expressions and the reactions. On one particular page [see image below], I eliminated the dead bodies entirely because I wanted to show the moment when the German guilt actually set in and what it looked like. I wanted to show how the guilt was visually manifested in their faces and gestures. For me, there was almost something reminiscent of Renaissance paintings about that. Here I really felt that you needed to see what the cause was that led her to look like this.

In the next photo [see below], you have an idyllic landscape that looks very innocent, but the photo shows the contrast of what was actually happening all this time underneath the surface, which we were completely unaware of. In the photo, you can see this; you can experience this ignorance in a way. I think that it is very important to show these images, but it is also equally important to think about how you show them.

George Dalbo is the Educational Outreach Coordinator for the Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies and a Ph.D. student in Social Studies Education at the University of Minnesota with research interests in Holocaust, genocide, and human rights education. Previously, he was a middle and high school social studies teacher, having taught every grade from 5th-12th in public, charter, and independent schools in Minnesota, as well as two years at an international school in Vienna, Austria.

Comments