I dream of a Digital India where access to information knows no barriers – Narendra Modi, Prime Minister of India

The value of a man was reduced to his immediate identity and nearest possibility. To a vote. To a number. To a thing. Never was a man treated as a mind. As a glorious thing made up of stardust. – From the suicide note of Rohith Vemula 1989 – 2016.

A speculative dystopia in which a person’s name, biometrics or social media profile determine their lot is not so speculative after all. China’s social credit scoring system assesses creditworthiness on the basis of social graphs. Cash disbursements to Syrian refugees are made through the verification of iris scans to eliminate identity fraud. A recent data audit of the World Food Program has revealed significant lapses in how personal data is being managed; this becomes concerning in Myanmar (one of the places where the WFP works) where religious identity is at the heart of the ongoing genocide.

In this essay I write about how two technology applications in India – ‘fintech’ and Aadhaar – are being implemented to verify and ‘fix’ identity against the backdrop of contestations of identity, and religious fascism and caste-based violence in the country. I don’t intend to compare the two technologies directly; however, they exist within closely connected technical infrastructure ecosystems. I’m interested in how both socio-technical systems operate with respect to identity.

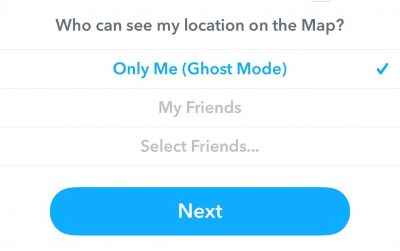

Snapchat recently released a new feature called Snap Map that lets users see the the location of their friends’ snaps organized on a map. The feature is opt-in only and carefully avoids unintended disclosure of user data. Snapchat even nudges users to actively manage who they share their location with. The

Snapchat recently released a new feature called Snap Map that lets users see the the location of their friends’ snaps organized on a map. The feature is opt-in only and carefully avoids unintended disclosure of user data. Snapchat even nudges users to actively manage who they share their location with. The