In a recent post that discussed why revenge porn victims feel such a strong sense of violation when images of their bodies are shared without consent, I argued that “the conversation about non-consensual pornography needs to be recentered from property rights, or even privacy, to the concept of ‘bodily integrity.'” In particular, I suggested it might be useful to reimagine our pics and profiles as “digital prostheses” that we incorporate into our sense of self. I concluded that “our pictures and profiles are not merely representations of us; rather, they are us, in some important sense.”

Reflecting on my personal history as a cam model, I want to talk about a related topic: How online sex workers experience loss of control over the images, videos, live streams, and profiles that we produce. A key question I want consider is how we ought to think about context and bodily integrity in a situations where we, as models, commodify our own bodies. Additionally, I want reflect on what role consent plays in such situations.

I did my first cam show in 2013. My graduate assistantship had ended, and I was looking for ways to pay rent while finished my comprehensive exams and tried to figure out if wanted to write a dissertation. I thought it might be a convenient part-time gig that I could fit in between school work and other small jobs I picked up. I was also just curious about it and whether I could make it work.

The fact that it was live made it feel safe. I didn’t expect a large audience that you can expect in a strip club if you are female or male stripper, so the odds of someone I knew wondering in my chatroom seemed pretty low. And, once I logged off, I’d be out of sight. In any case, it wasn’t very successful.

Not long after I started playing around with camming, I met Jessie (my now wife). She wanted to try camming with me. I quickly realized that, as a couple, the context had shifted. The typical size of the chatroom exploded from around a dozen to hundreds. Exposure was now a real consideration. What if we were recognized? Again, we consoled ourselves thinking that these shows were ephemeral and were limited to the audience of few specific sites.

Then, one day, we Googled our username. We were shocked to find pages full of screenshots and recorded shows spread across numerous sites that we didn’t recognize. I felt naive, even stupid, that I didn’t realize our performances were being so thoroughly documented. It’s not as though I didn’t know it was possible to capture and save streaming video, it just didn’t occur to me that anyone would be motivated to do so. We were struggling to attract enough tips and viewers to make even minimum wage.

I tried to have our content removed by filing Digital Millennium Copyright Act takedown request with the sites. A few complied but most ignored the requests (and, presumably, all US law). Some asked for us to reveal our legal names and other personal details as part of the process. Overwhelmed by the impossibility of controlling the circulation of these videos and images, we took a long hiatus from camming. We decided it was only worth the risk or exposure if we had the time and energy to be successful—to put on shows several times a week and to spend even more time building a following on social media.

On one level, piracy can be viewed as a “job hazard”—something to be factored into the economic calculus of whether the job is worth it. But, like the sexual assault that strippers and escorts often encounter on the job, it cuts deeper than mere economic calculation. In fact, the theft and potential loss of income wasn’t even the part that made us most upset; it was the loss of autonomy and self-determination. Our bodies were being portrayed in ways we never consented to.

While we chose to be naked on the internet, we intended for those performances to be ephemeral and bounded to a specific site. The screenshots—taken at random intervals—often felt even more upsetting than the recorded video. Apart from being profoundly unflattering—often catching us as we shifted positions—they chopped up our interactions, making them appear to be less loving and more graphic than they appeared in context. They dissected our sex in a way that felt alien to us.

Our reaction was personal—emotional—more than dispassionately economic. We felt violated. From this perspective, calling it “piracy” seems like somewhat of a misnomer. But, making sense of this experience of violation requires confronting some difficult questions about the nature of both digitally-mediated interaction and of sex work.

Even as personal digital communications technologies were just beginning to take root in the early 90s, Sandy Stone’s foundational work on “prosthetic sociality” (particularly in regards phone sex) and Julian Dibbel’s account of “A Rape in Cyberspace” presaged the inevitable integration of such technologies into human sexual agency and the possible dangers therein. Stone, in particular, warned against the tendency to treat the Web as a collection of information, reminding us that inside the computer’s “little box” is “other people.” Digital media users follow a long established pattern of people integrating new technologies of interaction into their sexual agency (just as they did with the telephone and written letters before that). In fact, Stone suggests that, as computers became increasingly available for personal use, their incorporation into play—and, in this case, erotic play—became inevitable.

If erotics describes expressions of agency with regards to pleasure, networked computers open the possibility of a new erotics: these digital prostheses have enabled us to “touch” each other in new ways. As Sarah Nicole Prickett observed:

There is nothing like talking to somebody IRL, it’s true. There is also nothing like body language or like the feeling of being looked at when you want to be. But when it’s good there’s really nothing like sexting.

Our new digital prostheses, like “all the earlier and other instances of codifying desire in a future-perfect way, like erotic letter-writing, like sex-room chatting, like getting illicit with it on AIM” (Prickett’s words again) are new expressions of, and encounters with, human agency. However, where agency can be expressed, it can also be denied or negated. So, these technologies also make possible new experiences of violation. Revenge porn, perhaps, being the quintessential case of such digitally-mediated violation.

The issue of digitally-mediated agency and violation is further complicated in the context of sex work, because the agency of (even offline) sex workers is already disputed. The work we do is often framed as “selling our body” for money. This implies a sex worker gives up their right to self-determination with regards to their body and forfeits it to the client as a detached, lifeless object. Not only does this diminish all of the imaginative and emotional effort that goes into sex work, it reduces it to a mere act of domination where the client is the only recognized actor. This framing—more than sex work itself—objectifies sex workers, portraying us as objects divorced from any intentionality.

The sex-worker-as-inert-object frame conflates consent with desire: We can only consent to the things that we desire. Desire, in turn, is essentialized—seen as an end in-itself. This perspective leaves little room for context and eschews any secondary motivations behind sexual interactions (dismissing not only financial incentives, but also things like care or creativity).

But this is not at all how independent sex workers think about consent or experience their work. In Playing the Whore (p. 91-3), journalist and former escort Melissa Gira Grant argues:

Sex workers negotiate based not only on a willingness to perform a sex act but on the conditions under which their labor is performed […] The presence of money does not remove one’s ability to consent. Consent, in and out of sex work, is not just given but constructed, and from multiple factors: setting, time, emotional state, trust, and desire. […] It would be a mistake, then, to confuse desire with consent. There is much that sex workers do in their work that they will not enjoy doing, and yet they do consent and have legitimate reasons for doing so.

So, while it is already difficult to get people to recognize the consent and agency that we express with regards to our flesh-and-blood bodies when doing sex work, it is even more difficult to convince people that we are also expressing agency through the digital artifacts of our sex. Arguably, understanding the deep connectedness most cam models and clip producers have to their work should be no more complicated than understanding that being called ugly based on a Facebook pic would probably invoke negative feelings similar to what you’d experience if that person said the same thing to your face. In practice, it’s a much harder case to make. I think this comes down to the fact that, as online sex workers, we are commodifying the “content” that we produce.

But as Melissa Gira Grant suggested with regards to full service sex work, putting a price tag on something doesn’t totally separate it from us. Thinking about sex workers’ (and other digital media producers’) content as disconnected from who they are as a person is a trap that Karl Marx called “fetishization.” Here, I don’t mean “fetish” the way we usually use it in the context of sex work (that use of the term is more connected to Sigmund Freud). Instead, I mean the tendency we have to forget about the human relations that make up a thing when it goes to market. This fetishization of commodities is particularly problematic when they are products of the digital communications technologies we use to express ourselves because, they not only bear the marks of our agency, but are still extensions of our agency in a very real sense. This is distinctly so for live, video-streamed shows, which feel far more like a platform for interaction than the creation of something separate from us.

Cam sites are technologies for models in the same ways stages are technologies for strippers from magic men; they elevate us and make us visible to a specific audience in a specific context. Whether it is ok to capture these performances and remove them from a context that we have chosen to make them visible is at least as much a matter of consent as it is a matter of theft. That is to say, cam piracy has as much in common with revenge porn as it does with illegally downloading movies from Pirate Bay.

And, just like cam models, strippers have also struggled with audience members making non-consensual recordings. For example, the workers at San Francisco’s Lusty Lady peep show made the removal of one-way mirrors (which customers were using to surreptitiously record strip teases) a key demand in the unionization process. More conventional strip clubs have also had to develop policies to regulate photography going back to the time mass produced cameras hit the market. Usually, clubs have a blanket ban on cameras, but a few venues like the Ivar Theater experimented with camera nights, which took a different approach and attempted to capitalize on the desire to document rather than simply forbidding it.

Like strip club, cam sites are now in the position to implement designs and policies that protect models from recordings or help models to capitalize on them—in other words, to offer models more opportunity to decide in what context, and under what conditions, they are accessible to an audience. Looking at the past example of strippers have organized to improve their conditions, I think we need to start imagining what collective action for cam models might look like. Particularly, this means foregrounding consent.

One big thing cam sites could do in the name if consent is to make clear statements to new models about the likelihood of piracy. Creating cam coach or model liaison positions for experienced/retired models is a particularly effective way that some sites have implemented to improve this sort of communication. There are also tools that sites could invest in to discourage piracy such as watermarking and digital fingerprinting. Additionally, limits on anonymous viewers is another design change that may make pirating more difficult. Furthermore, though the legal system is seldom sympathetic to sex workers, one could imagine creative criminal complaints — such asking that cam piracy be prosecuted under revenge porn laws or identifying sites that host pirated content as possible hubs of child porn because they lack the age verification records that models must file with legitimate sites. These legal options, however, would take serious lobbying efforts.

What’s clear is that making the case for any of these solutions will not be easy. Digital mediation adds another layer of complexity to understanding how sexual agency and its negation are experienced in the context of sex work. Not only are we asking people to recognize the way sex workers express agency through our own bodies, but also through other objects — our digital prostheses. We need society to understand that not just our bodies, but our content as well, is an extension of our self in deep and meaningful ways. And, though we commodify this content, it does not cease to be an intimate expression of agency.

For our part, Jessie and I returned to camming, but we hold back more now, assuming that everything we do is being recorded—that every second on cam is a possible screen shot. Because we cannot control the context of our exposure, it feels like we have to be hyper alert about controlling our image, imagining that everything we do will be visible to anyone at any time. We’ve accepted it, but camming now feels like a much bigger choice—like it’s not something we can just try. We have to be all in or all out. I’m left wondering what this will do to the amateurism that characterizes these sites, if the risks become too great for all but high-earning, full-time models. And, if so, will piracy hinder the spontaneity and diversity that makes cam sites such exciting places to be?

PJ Sage (@peejsage) is cam model and sex work researcher.

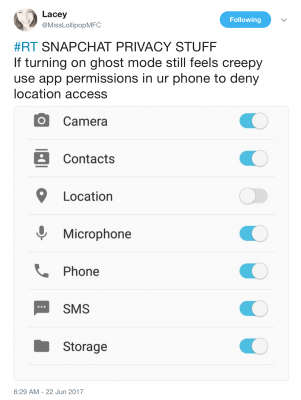

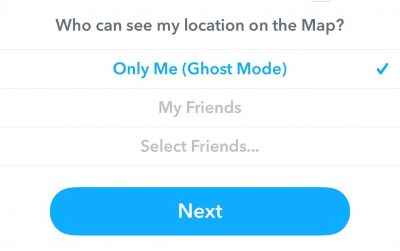

Snapchat recently released a new feature called Snap Map that lets users see the the location of their friends’ snaps organized on a map. The feature is opt-in only and carefully avoids unintended disclosure of user data. Snapchat even nudges users to actively manage who they share their location with. The

Snapchat recently released a new feature called Snap Map that lets users see the the location of their friends’ snaps organized on a map. The feature is opt-in only and carefully avoids unintended disclosure of user data. Snapchat even nudges users to actively manage who they share their location with. The