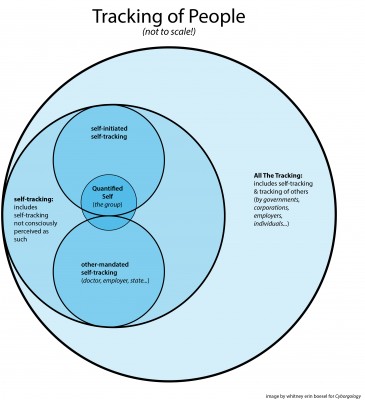

Earlier this week, I became aware of an art piece called “x.pose,” which is intended to make a statement about the data exhaust we generate and what large companies may or may not be doing with it. x.pose is a collaboration between two artists, and the first paragraph in a description of it on one of their websites reads as follows:

x.pose is a wearable data-driven sculpture that exposes a person’s skin as a real-time reflection of the data that the wearer is producing. In the physical realm we can deliberately control which portions our bodies are exposed to the world by covering it with clothing. In the digital realm, we have much less control of what personal aspects we share with the services that connect us. In the digital realm we are naked and vulnerable.

First, yes: digital dualism. I’ll set that point aside and come back to it later. Right now, I want to focus in on that first sentence, particularly where it says “exposes a person’s skin.” A person—sure, that could be any of us.[i] The sculpture exposes “skin” belonging to a person, a wearer. Data exposure is like bodily exposure. That’s not gendered, right?

Actually, it’s quite gendered. While x.pose draws attention to some important issues, it also starts from a number of problematic assumptions and reinforces some of the most sexist and patriarchal strains of privacy critique. Just in case you had any doubt, here’s what the piece looks like:

Newsflash: We can’t all wear that.

x.pose is a collaboration between two people, Xuedi Chen (who uses feminine pronouns on her website) & Pedro G. C. Oliveira (who appears to be masculine-presenting in photos of x.pose’s construction). Making it was a pretty involved process, so, sure: they only made one—it’s an art project, not a ready-to-wear production run. And since Chen designed the project to explore her own relationship to her data, it makes sense that she and Oliveira would construct x.pose to fit a woman’s body rather than a man’s (as shown, model Heidi Lee). Plus, let’s face it: no one makes a statement piece with the intention that it will be ignored. A transparent women’s top is far more salacious than a transparent men’s top, and the torso cut-outs and strapless design (as well as Lee’s heavy makeup) make it clear that x.pose is supposed to be viewed in a sexual light. Whether in the capitalist economy or the attention economy, sex sells.[ii]

The fact that x.pose was designed by a woman (and for personal reasons), however, does not negate the sexism and slut-shaming of its message. x.pose starts from two explicitly stated assumptions: 1) that we unknowingly expose our data, and 2) that this exposure leaves us naked and vulnerable. Starting from these assumptions, the artists have created a shirt that becomes transparent when the person (woman) wearing it is exposing her data. If viewed in a cultural vacuum, the response is, “So what?” Her data is showing, and so her breasts are showing. Naked is just naked. Who cares?

If we exit the hypothetical cultural vacuum and reenter contemporary U.S. society (both artists live in New York), it becomes obvious: The meaning of x.pose hinges on the meaning of breasts.

Here inside Culture, x.pose becomes intelligible. We know that showing data is “bad” because showing breasts is “bad.” A woman’s nudity is obscene, a danger to society. Even a glimpse of a woman’s body can be a danger to the woman herself, as the grotesque phrase “asking for it” and the repugnant question, “What was she wearing?” remind us. The unsanctioned, visible breast is a harbinger of conflict and backlash: a “wardrobe malfunction” costs more than a half-million dollars and, despite breastfeeding’s protected legal status, women who do so in public are routinely told to “cover up” or to leave public places. The unsanctioned, involuntarily visible breast is the worst one of all: “revenge porn” is a thing[iii], and a photograph of breasts can incite enough abuse to drive a young woman to suicide.

Exposed breasts are bad, and potentially dangerous; exposed data equals exposed breasts; exposed data is bad, and potentially dangerous.

Now we have the “So what”: The shirt becomes transparent to remind the woman wearing it that by spreading her information, she is at best committing indecent exposure and at worst tempting someone to violate her. The shirt also serves to make the woman wearing it an example to everyone around her: check your settings, tug down your hem, button your blouse. Abstinence only, please—or you’re asking for it. Keep your knees (bits?) pressed together, and cover up already. Surely you’re not trying to show your data to everyone, you [insert choice of sexual slur here]. It’s the same tired, victim-blaming, “Shame On You” strain of privacy critique, this time made patently manifest in fetching high-tech couture.

Chen and Oliveira’s description goes on to elaborate,

In today’s data-driven society, individuals carrying smartphones and interacting with social media networks have agreed, often without conscious consideration, to policies that grant service providers explicit rights to harvest and utilize personal data on a massive scale. These include companies like Google and Facebook that offer “free” services for a value exchange of our data.

There currently exists a paradox in our internet culture. As a generation, we are simultaneously obsessed with publicity and privacy. While we publish and post details about our lives online, at the same time we demand the most advanced privacy protection software. An unprecedented degree of potential exposure comes with the current mode of existence.

I have ceded control of my data emissions and Based on my activity logs, Google clearly knows where I am, where I’ve been and possibly even where I’m going. Yet when I wanted a log of my location history, I had to go through numerous steps to “enable” tracking…

By participating in this hyper-connected society while having little to no control of my digital data production, how much of myself do I unknowingly reveal? To what degree does the aggregated metadata collected from me paint an accurate portrait of who I am as a person? What aspects of my individuality are reflected in this portrait?

x.pose is my exploration of these questions. Since I have already ceded control of my data, I wanted to go a step further and broadcast it for anyone and everyone to see.

Again, if you translate this into sex instead of data—which x.pose itself is encouraging us to do—the rhetoric is clearly problematic. Facebook invited you over late at night and, “without conscious consideration,” you said yes; you should have known better. Google offered you a drink and, since it was free, you said yes; you should have known that the drink was spiked with roofies. You went out wearing that short skirt, and then had the nerve to demand that Online respect your boundaries and stop at making out? You got drunk with Google and lost “control,” so of course it had its way with you (and then pretended the next day that nothing had happened). Don’t be so surprised.

The fact that Chen and Oliveira only made a women’s version intensifies x.pose’s slut-shaming aspects and, whether they intended to make a gendered statement or not, x.pose has been read as something for women. For instance: What Chen and Oliveira describe as “a data-driven wearable sculpture” (shown covering the top part of Lee’s body) has alternately been described as “a 3D-printed sculptural boob tube,” an “interactive dress,” a “3-D printed dress,” a “data driven dress,” or a “naked dress” (occasionally, a “bustier” or a “corset“). That’s how othering works: Others are marked, and only Subjects can stand for everyone. Even if Chen and Oliveira intended x.pose to be “political, not sexual,” as one commentator (who calls the piece a dress) wrote, out in the world, x.pose is political and sexual. Lee’s body can only represent women’s bodies—not because that’s how things should be, but because that’s how U.S. culture currently is. Women’s bodies are profoundly sexualized—and in western cultures, Asian women’s bodies are “associated with sex to the point of absurdity.” This is in no way to say that Chen’s concept should not be modeled by someone who shares her race and gender identity. It is to say that, in the U.S. context, x.pose will never not send extra messages about women’s bodies and women’s sexuality.

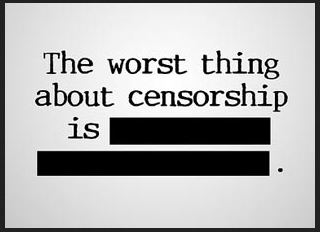

And still, the problem with x.pose is rooted not in its execution, but in its concept. ALL visibility-shaming comes back to slut-shaming. The slut-shaming would be there even if Chen and Oliveira had made his-and-hers versions of x.pose; even if they had made one and instead fit it to a man; even if they had made one to cover and reveal a gender-indeterminate portion of a body. Like slut-shaming, digital-visibility-shaming denies agency by presuming everyone is a victim (or a future victim), and by condemning those who transgress by proclaiming the intentionality of their choices and actions. Like slut-shaming, digital-visibility-shaming blames victims for any harm that comes to them and, in so doing, deflects attention from the more powerful actors who harmed others in the first place. Rather than confront the state of our society, we blame the people who “allow” themselves to be hurt by its worse elements. We treat people—and especially, women—who are naked, sexual, or visible as “bad” not because of anything they are or do, but because of what other people might do to them. And that needs to change.

To be clear, x.pose does touch on some very important issues. Digital media companies—especially huge ones like Google and Facebook—do have a lot more power than most of their users. They have used both their policies and the design of their platforms in outright attempts to shift social norms, and have done so with a mind-boggling ignorance of how social interaction works. Our very conceptualization of privacy is in flux, and Silicon Valley keeps trying to tell us that that means privacy is dead. A lot of people find Facebook’s constantly shifting privacy settings to be utterly confounding; unless you’re a lawyer, forget about trying to read an actual ToS or privacy policy. Many people cannot “opt out” of these services, whether because their schools and workplaces use Google products or because the high social cost of abstaining from social media isn’t one they can pay. Visibility can absolutely be vulnerability, especially for marginalized Others. This isn’t just about “the digital realm”; there is no such thing. This is our (one) world, and our always-embodied everyday lives.

I care about these things a lot, and I’ve been writing about them on Cyborgology for two years now. But to everyone who comments on these issues, whether in text or in image or in any other format: Please, enough with the shaming and the victim-blaming. We need to get over obsessing over what “we show,” and turn our attention toward who does what to whom. Breasts—whether biological or metaphorical—are not themselves the problem.

Whitney Erin Boesel (@weboesel) gets accused all the time of posting “everything” online. Depending on her mood, she laughs, glares, or rolls her eyes.

Lead photo of x.pose: Image credit Roy Rochlin, from Xuedi Chen’s website.

———

[i] I’m guilty of this, too, but as I love to tell students: Always Question the Assumptive We. Who is “we,” really? Though further into the description it becomes clear that the project is geared toward social media users (and in particular, smartphone owners), here the unqualified “we” is the one we’ve been taught to read as a nebulous “everyone.” Obviously, this does not apply to everyone. Even aside from the points I’ve made above about choice and intentionality, only 58% of U.S. adults own smartphones. While the formal definition of “everyone” is “every person,” I think the Urban Dictionary definition for “everybody” captures more of what’s going on here: “All people whose existence the speaker deigns to acknowledge. Generally limited to those with similar interests and vocabulary.”

[ii] While, say, men’s underwear models are making headway in the “masculine bodies=sex=sales” department, women’s bodies are sexualized to an extent that allows a woman’s body in-and-of itself to symbolize sex and sexuality. This is particularly true of women’s breasts, which is why so much of the U.S. (to say nothing of Facebook) has a meltdown over public breastfeeding.

[iii] Revenge porn victims are predominantly, though not exclusively, women and girls.