For many people, moving—especially to another city, state, or country, instead of just across town—is an opportunity to sort through (and likely, discard) possessions, in hope of making the impending relocation process less of an ordeal. I did this when I moved back to Massachusetts from California last February; I actually gave away more than 65 percent of my worldly possessions (by volume) before trading a two-bedroom house in West Oakland for a one-bedroom apartment in Cambridge. This pales in comparison, however, to what my parents are currently undertaking: After 28 years in the same house, they’re preparing to move across state lines next month. For them, July has so far been all about sifting through the accumulated sediment of so much time in one enclosed space; since this is the Internet age (and since my mom has access to a scanner), for me July has been all about a steady stream of emailed highlights from rediscovered family—and personal—history.

Now, don’t get me wrong: I save stuff, and I have for a long time. Initially, as a prepubescent kid, I’d wanted to make sure that who-I-would-become would have a way to access who-I-had-been; I was afraid that, from the ignorance of forgetting, my adult self would fail treat her own someday-children with compassion. Over time my concern has shifted from, “When I am an adult, I will not remember what it was like to be a child,” to “When I am senile, I will not remember what it was like to be me,” but both fear of losing my empathy and fear of losing my identity have made equally effective documentary drives. Among the things I dragged to California and back again are small boxes of ticket stubs, received letters, old journals, longhand rough drafts, scrawled-on paper scraps, filled-up notebooks, the occasional school assignment, and paper photos from back when lab prints were the default, among other things. If informally and in a disorganized manner, I have through these artifacts documented at least some aspects of what my experience of being in the world has been.

What I didn’t think about until recently, however, is that I have only captured my existence from my own perspective. In contrast, you know who has a very different curatorial eye, and direct access to a whole lot of material?

Yeah, that would be my mom.

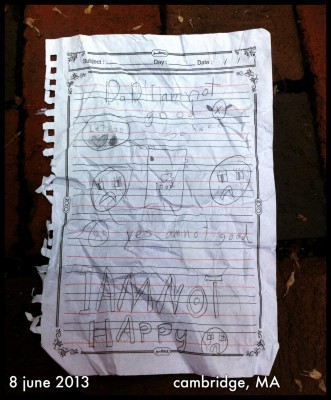

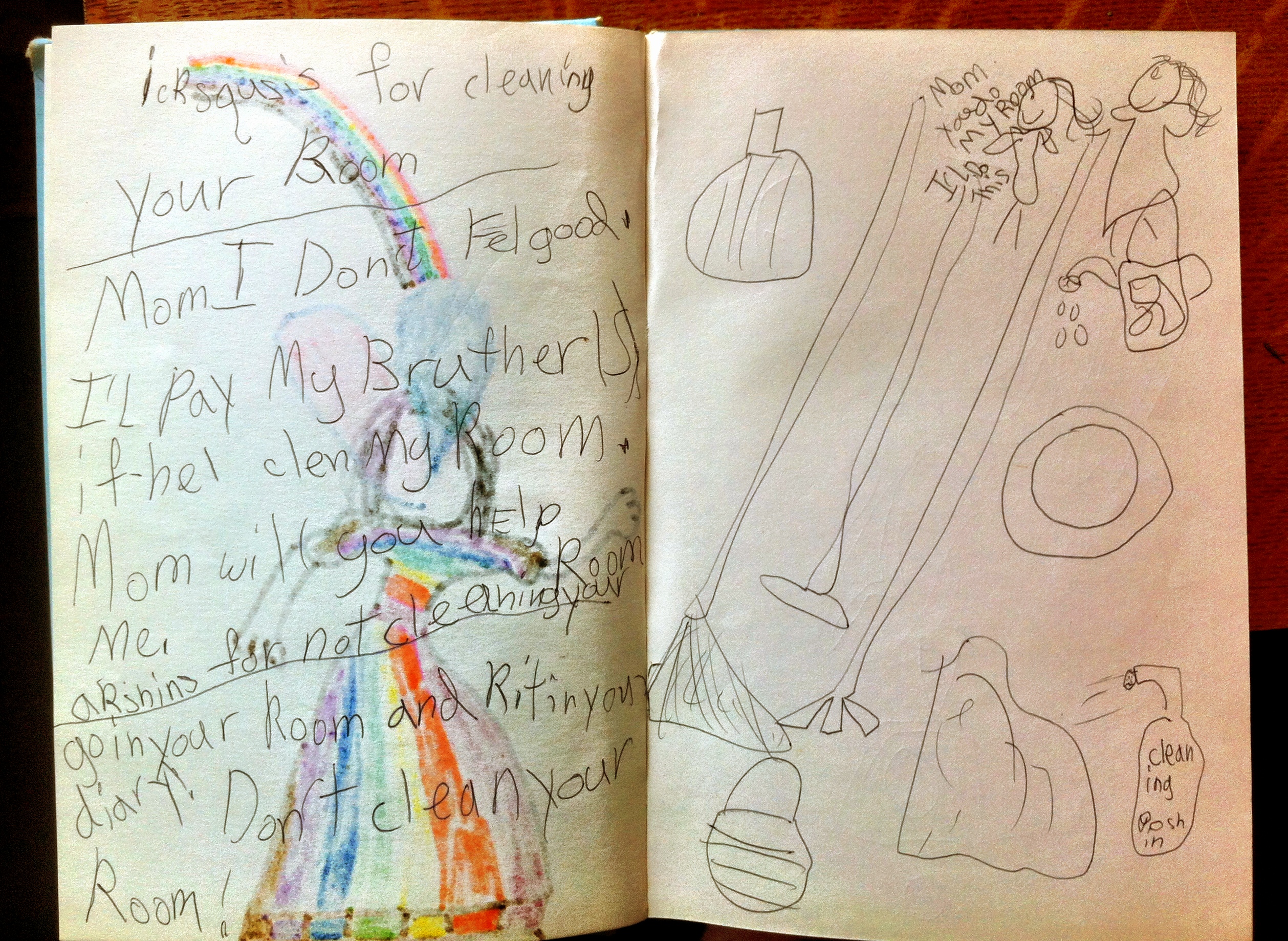

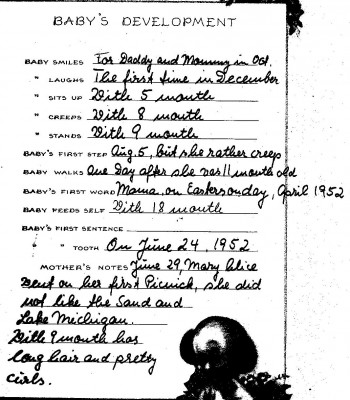

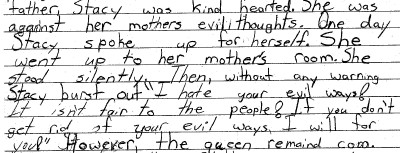

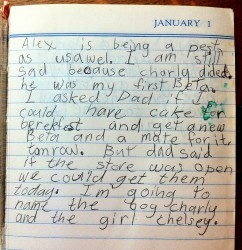

And holy crap, you guys: my mom’s got archives. My mom has saved stuff I don’t even remember making, artifacts created by a creature so tiny I can’t remember inhabiting her body without digging up a book with a tarnished lock and the word “DIARY” embossed across the front. There are things like preschool art projects, things I probably gave to my parents, but also things like stories scrawled on legal pads that I have no idea how my mother ever came to have, other than perhaps through some magical, panoptic parent voodoo. There are other things I vaguely remember writing, but that it never would have occurred to me to save (such as a particularly tongue-in-cheek rejoinder to an automated response from the email system at my mother’s place of employment, after my enthusiasm for swearing tripped a newly-installed spam filter). I have no idea where they were keeping all this stuff, but as my parents keep going, the scans keep coming—and those documents of documents are kind of amazing. Though I was only dimly aware of it at the time, it’s now quite apparent that my parents (mostly my mother) were engaged in a documentary project that paralleled my own, but that captured a notably different piece of my life.

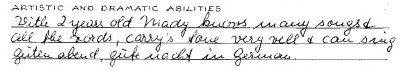

To a lot of people—or at least, to a lot of people who are vaguely near my age and who share a roughly similar class- and cultural background—this is not particularly unusual. Saving Stuff From Childhood is just what parents, and especially moms, are supposed to do (or so we’ve been told); though the practice doesn’t have a name, we know what it is and we more-or-less expect that it takes place. Viewed through another lens, however, we can frame parental archiving as something else: as a kind of child-tracking. Some commonplace child-tracking practices are direct and quantitative, like a collection of report cards in that one kitchen cabinet, or a doorway with dates and dashes denoting height; other practices are more informal and qualitative, like a collection of stories over which one can watch my handwriting slowly solidify, and my spelling slowly become less “creative” (to use my mother’s term). Far from being the exception, then, the parental tracking of children and childhood seems almost mundane, the expected norm.

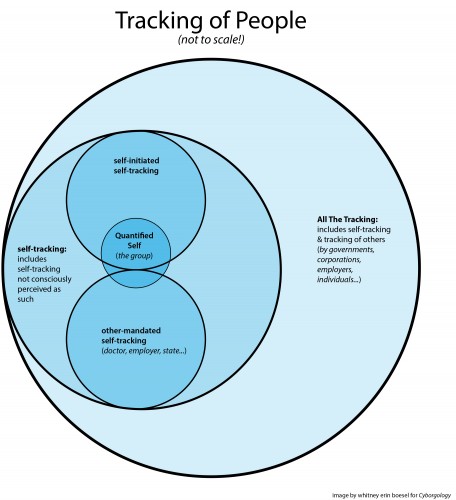

Or so you’d think. Earlier this week, Slate published an article titled, “I Measure Every Single Thing My Child Does,” which is about exactly what you’d think it’s about. Here, the child-tracking practices in question look a lot more like the kind of highly quantitative self-tracking that takes center stage in media coverage of Quantified Self, and a lot less like my family’s disorganized salvaging of early artistic endeavors. There are spreadsheets, and detailed measurements, and subjective observations coded as Likert items, some of which begin well before the titular child (a daughter) is actually born; notably the author, Amy Webb, is also the author of the book Data: A Love Story (so this is a family, or at least a couple, whose collective enthusiasm for “data” is likely greater than that of most other American parents). While I don’t know if Webb has ever been to a Quantified Self event, the story she tells in Slate does resemble what I’ve come to see as a classic QS narrative: “I track, and though my data I come to know myself better, and through this self-knowledge I’m able to be better”—a better (more healthy, more productive, happier) version of myself, or perhaps a better worker or a better partner. Webb’s story, however, has an interesting twist in the identity department: the thrust of her essay is, “I track, and through my daughter’s data I come to know my daughter better, and through this knowledge of her I’m able to be a better parent.” Webb therefore implicitly captures what I’m finding to be an increasingly fascinating question with respect to Quantified Self: where exactly does “self” stop, and “other” begin?

Several friends and colleagues sent me Webb’s article when it came out (I love it when that happens), and there was a discussion about the piece in my Twitter feed as well. Overall, reactions from within my circles tended toward the negative: some wondered if the article was a satire, while others posited that, “[the] experience [of tracking] enables activities that begin as caution to transform into absurdity.” To be fair, Webb does acknowledge that her child-tracking practices “might seem obsessive, ostentatious, or just plain weird”; though she offers an argument for how such practices have benefited her family, she doesn’t exactly go out of her way to make them seem any less abnormal. My own first thought, however, was less about normalcy (or lack thereof), and more about “this isn’t exactly new”—although a sociologist saying, “This isn’t new” is just about the least-new thing that there is. Instead of stopping at “that’s not new,” then, I want to spend the rest of this post thinking about why Webb’s child-tracking practices aren’t that new. I threw out the term “QuantBaby” on Twitter in part as a joke and in part as a piece of character-saving shorthand, but if we consider “QuantBaby” to stand for the detailed, quantitative tracking of one’s child and one’s child’s development, what preconditions have laid the groundwork for QuantBaby to be A Thing?

To answer this one, I think you have to back—back before the turn of the 20th century, when three key things were happening: a decline in infant mortality, the shift to an industrial economy, and the coalescence of institutional medicine.

* * * * *

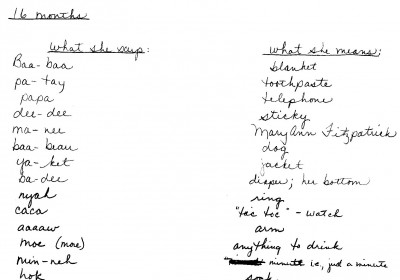

Consider the baby book, one of the oldest mass-produced tools for child-tracking. Baby books first started to emerge in the late 1880s, which historian Janet Golden credits in part to a decline in infant mortality: both the experience of raising a child and the child itself seem altogether different things once it’s more certain than not that the child will live past childhood. And yet, the mass-market baby books that appeared slightly later reflected something else as well: the shift toward an industrialized economy. As one author puts it, “Businesses discovered that babies are a wonderful excuse for consumption.” Consumer goods need consumers in order for an industrialized economy to work, and the early baby books printed by companies such as Borden’s and Carnation helped to create consumers for baby products in two important ways: first, by serving as a convenient vehicle for advertisements; and later, by helping to recast children not as something one created out of obligation (or a need for farm labor), but as a source of emotional fulfillment. From the beginning, baby books structured “good parenting” as something that involves a lot of metrics; this was due in part to the popularity of the Child Study movement at the time, and was also probably not unrelated to advertisements for rentable baby scales. Later, as both “childhood” and “the family” were reconfigured in the postwar era, baby books—along with new experts like Dr. Spock—prompted parents to record developmental milestones as well as raw quantitative metrics. Good parents still tracked, but now they did even more tracking—at least, in theory; even a hundred years ago, oldest children were much better documented than were their subsequent siblings. (As Golden points out, third or fourth children are rarely documented at all.)

The medical profession, too, has played an important role in the rise of parental child-tracking. The professionalization of medicine was gaining momentum at the turn of the 20th century, and pediatrics itself was emerging as a medical specialty (the American Pediatric Society was formed in 1888). All “experts” need a field of expertise, and this new class of experts—pediatricians—staked their claim to authority not just in matters of childhood sickness, but in “infant feeding, child hygiene, and disease prevention in well children” as well. Up until this point, institutional medicine had considered childhood illnesses to be within the purview of obstetrics, which was itself still in the process of wrestling authority away from a long tradition of midwifery; accordingly, the establishment of pediatrics as a profession was doubly-dependent on the assertion that pediatricians hold some sort of “special knowledge” unavailable to lay practitioners or to parents themselves. As sociologist Eliot Friedson argues in Profession of Medicine, institutional medicine draws its power in part from a state-sponsored monopoly on defining what counts as ‘normal’ as opposed to ‘abnormal,’ ‘sick,’ or ‘deviant’; if one’s area of practice is children and their growth, how better to delineate “normal” from “abnormal” development than through tracking individual children and comparing their numbers to aggregate data sets?

For many parents (who have access to medical care), child-tracking therefore begins in the pediatrician’s office, with or without a baby book. None of my friends who have children have tracked their children QuantBaby style, for instance, but all of those friends could tell you during their children’s infancies where their children fell in “the percentiles.” (As one friend explained, it was fine that her child was below the 20th percentile for both length and weight; as long as that stayed consistent, there was no cause for concern. While a dramatic shift in percentile placement could indicate some kind of problem, my friend’s daughter was simply “petite.”) When we recall that “educating” (socializing) parents into their roles-as-such was among pediatricians’ initial institutional goals, is it any wonder that parents—especially those with access to pediatricians—might associate child-tracking with fulfillment of their parental duties? (And similarly, is anyone that surprised that Webb’s pediatrician was irritated when she brought her own spreadsheets, rather than automatically accept his professional authority and the authority of his discipline’s metrics?)

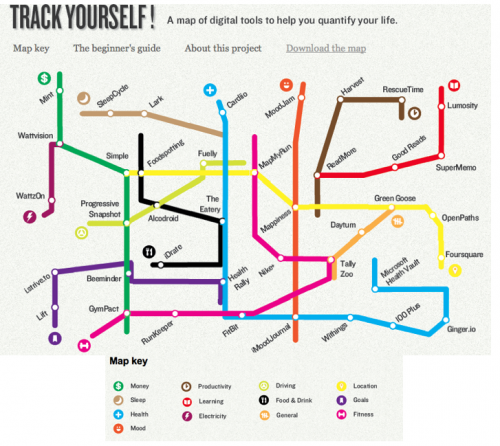

But what else might lead present-day parents track their children, and why might they do so at the level that Webb has? Some of it, undoubtedly, is due to the affordances of available tools: a print baby book with blanks to fill in encourages certain types of observations, whereas if what you have is an Excel spreadsheet (and we do know Webb loves spreadsheets), “every single thing” might start to look like a numerical value. Tools and affordances, however, are only the beginning. Start with the availability of digital child-tracking tools, which—like print baby books before them—will shape and structure “good parenting” in different ways, according to the end goals and values of whoever has produced them. Consider that pediatricians similarly socialize parents into child-tracking generally, and into quantitative child-tracking specifically, through the use of percentile comparisons and normative expectations for developmental milestones. Remember that (for many people) tracking is an expression of agency, an attempt to gain control—or at least, the feeling of control—over something that is vast and unknowable and possibly frightening, and that to first time parents awash in modern risk rhetoric, a helpless infant is pretty unknowable and frightening (or so I hear).

There’s a lot at stake in a present day child, especially if she’s the only child of somewhat older upper-middle class parents (as Webb’s daughter is). Such a child is not just a person, or a person-to-be; she also reflects on the person or people who created her. As Barbara Katz Rothman points out, the commodification of children has led privileged parents in particular to feel anxiety about producing “blue ribbon babies”; where a “healthy” baby once sufficed, now only an overachieving, exceptional baby possessed of “desirable attributes” will do. Privileged parents are far from the only ones to feel these anxieties, however; you can observe any parent’s internalization of developmental norms (for example) in the pride they take when their kids do something “early,” and in their embarrassed justifications for when their kids do something “late.” (In my family, for instance, my mother will tell you that I started walking “late” because I started talking “so early,” and so had figured out how to make people bring me the things I wanted; my brother, on the other hand, walked “early” and talked “late” because I “did all the talking for him.”) Parents want their children to be successful not just because they love those children and so want them to succeed, but because they themselves cannot be “successful parents” without raising “successful children.”

This, then, hits upon my final point, which is the complicated interplay between a parent’s identity and her child’s identity. We tend to put more emphasis, I think, on the way parents shape their children’s identities, but in truth a parent’s identity is equally shaped, if not defined, by her child. Children “fail” or “succeed” according to a complicated interplay of factors (not the least of which is how “success” and “failure” are defined), and yet inevitably, we blame or credit parents—mothers, especially—for the actions and achievements of their children. How often have you heard someone speak of a troubled child by asking, “Where are the parents?” How often do you hear the phrase “a good family” in the same breath as mention of a child’s laudable accomplishment? Even “good parents” of “bad kids” are accorded pity, not respect; if adults want status as “good parents,” they have to produce the appropriate child or children as proof.

When you stop to think about it, that’s an awful lot of personal identity performance riding on someone who isn’t actually you yourself. And yet, it’s hard to get around it: many parents take their kids very, very personally. Webb, for instance, relates an interaction with the mother of another student in her daughter’s ballet class, and it’s plain that their conversation has nearly nothing to do with the two little girls on the other side of the classroom mirror. The other mother boasts about her daughter’s physique, and expresses “concern” about Webb’s daughter’s facial expression, but the comments are far more about Webb’s daughter as an extension of Webb herself; similarly, Webb puts the other mother back in her place (at least, in the article) by judging the other daughter’s demeanor. Presumably without knowing much about the other mother’s parenting methods, Webb presents the contrast between the two girls’ moods after class not just as evidence that her own parenting methods are superior, but that she herself is a superior parent. Alternatively, one could also consider the clichéd image of parents who are over-invested in their children’s sports games, and who scream at coaches and referees. Both types of interaction reflect competition between adults projected onto their children, and both are rooted in the same underlying assumption about parental status and identity: “My kid is or does, therefore I am.”

Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised, then, if some child-tracking practices are starting to resemble some self-tracking practices. Children are in many ways cast as extensions of their parents’ selves, both emotionally and socially; how much of child-tracking, then, is tracking one’s child’s development, and how much is tracking one’s own development as a parent? Similarly, children are vulnerable, and parents can never control their children to the extent that they’d like; child-tracking might therefore seem to offer the possibility of accessing hidden power-knowledge, of gaining greater protective control, of somehow warding off the unknown yet terrifying inevitable. Children themselves can be strange and unknowable beings, both before they develop a capacity for language and perhaps even more so after; given that parents have already long been encouraged to track their children, it makes sense that some parents would move to help their children “speak through the data.” Is it that big a leap from recording a list of made-up words to filling out one of Webb’s spreadsheets, at least while we’re still talking about infants and toddlers?

I do wonder what will happen, however, when Webb’s daughter gets older and wants to speak for herself—as in speak with her words, not through her data. (That assertion of independent, individual identity happens with all Western children, or so I’m told.) Perhaps as Webb’s daughter gets older and gains a greater ability to speak with words, her parents won’t feel they need “data” as an intermediary; perhaps “the data” will come to reflect that Webb’s daughter finds the tracking distressing, and the Webbs will decide to stop. Perhaps Webb’s daughter will rebel by skewing “the data,” and engaging in some database vandalism as an act of resistance; perhaps the answer will be “none of the above.” In any case, Webb’s child-tracking will become less self-tracking and more other-tracking as her daughter becomes her own self, and I wonder if—and how— that will be reflected in the numbers.

Whitney Erin Boesel has so far escaped her mother’s curse that she give birth to three daughters just like herself. She does have a cat though, and a Twitter account: she’s @phenatypical.