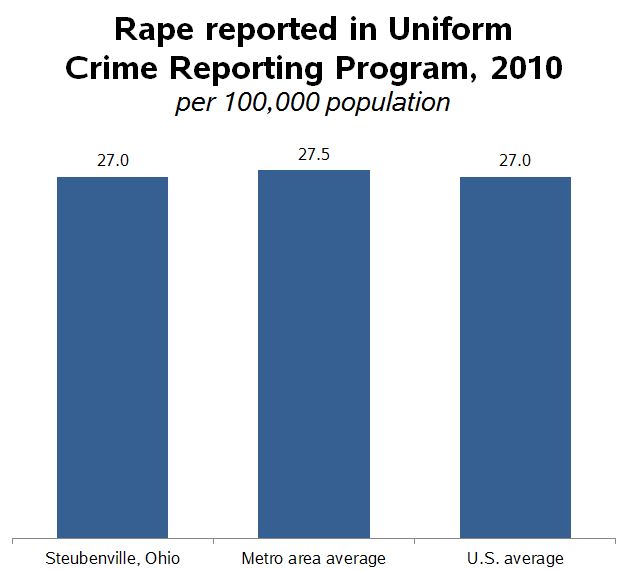

Philip Cohen, at Family Unequal, used FBI crime reports to put together this telling graph:

We need to remember that Steubenville is us and we are Steubenville.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.