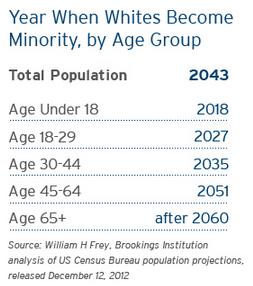

The year during which the U.S. will become a “majority minority” is well discussed. It looks like it’s going to happen sometime around 2050 or earlier. This statistic, however, elides an interesting subplot: the year various age groups will be majority minority.

Over at The Society Pages Editors’ Desk, sociologist Doug Hartmann offered the following table. It shows that children under the age of 18 will be majority minority 32 years earlier, by 2018. Young people ages 18-29 will join them by 2027. By 2035, people aged 35-64 will be majority minority. People 65 and older are quick to follow.

This data reminds us that demographic change is gradual. The year 2018 is just five years away. If young people continue to vote in numbers similar to those in the last two elections, their changing demographics could push forward a change that looks all but inevitable in the long run.

In the meantime, we need to be vigilant about how younger people are portrayed. Today poverty is racialized so as to demonize social programs designed to help the less fortunate. Can we imagine a future in which public education and other youth-oriented programming is similarly framed: as white people helping supposedly undeserving people of color? This is likely something that we should be vigilant against in the coming years.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.