Flashback Friday.

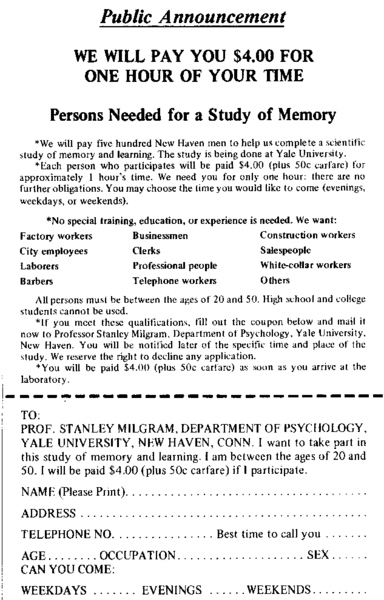

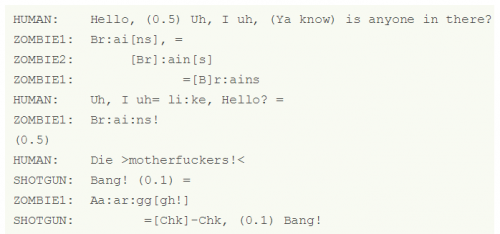

Bewildered by Nazi soldiers’ willingness to perpetuate the horrors of World War II, Stanley Milgram set out to test the extent to which average people would do harm if instructed by an authority figure. In what would end up being one of the most famous studies in the history of social psychology, the experimenter would instruct study subjects to submit a heard, but unseen stranger (who was reputed to have a heart condition) to a series of increasingly strong electric shocks. The unseen stranger (actually a tape recording) would yelp and cry and scream and beg… and eventually be silent. If the study subject expressed a desire to quit administering the shocks, the experimenter would prod four times:

1. Please continue.

2. The experiment requires that you continue.

3. It is absolutely essential that you continue.

4. You have no other choice, you must go on.

If, after four prods, the subject still refused to administer the shock, the experiment was over.

In his initial study, though all participants at some point required prodding, 65 percent of people (26 out of 40) continued to submit the stranger to electric shocks all the way up to (a fake) 450-volts, a dose that was identified as fatal and was administered after the screaming turned to silence. You can watch a BBC replication of the studies.

Originally posted in August 2010.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.