Women in the U.S. have made some monumental gains at work. We’re now at least half the labor force and more women today are middle- and upper- managers in corporate America. Even so, I wasn’t surprised to discover that women have not (yet) made similar inroads into high-level corporate crime.

Rather, it’s “business as usual” when it comes to who is responsible for orchestrating and carrying out major corporate frauds.

For the American Sociological Review, Darrell Steffensmeier, Michael Roche, and I studied accounting malpractices like security fraud, insider trading, and Ponzi schemes in America’s public companies to find out just how involved women were in these conspiracies. The Corporate Fraud Task Force indicted 436 individuals involved in 83 such schemes during July 2002 to 2009. We read and recorded information from indictments and other documents or reports that described who was involved and what they did.

I expected the share of women in corporate fraud to be low – definitely less than the near-half that are women among (low-profit) embezzlers arrested each year– like your bank teller or local non-profit treasurer. However, I was surprised that women corporate fraudsters were about as rare as female killers or robbers – less than 10% of those sorts of offenders. Of the 400+ indicted for corporate fraud, only 37 were women.

Most of these frauds were complex enough to require co-conspiracy over several years and a criminal division of labor. Often, women weren’t included at all in these groups. When they were, they were nearly always in the minority, often alone, and most typically played rather small roles.

The Enron conspiracy, for example, led to over 30 indictments; three were women and each played a minor role. The five women indicted among 19 in the HealthSouth fraud were in accounting-related positions and instructed by senior personnel to falsify financial books and create fictitious records. Martha Stewart, rather than criminal mastermind of an insider trading conspiracy, committed “one of the most ill-fated white-collar crimes ever” in which she saved just $46,000 after receiving a stock-tip second-hand from her broker.

Women were almost never the ringleader or even a major player in the fraud. Only one woman CEO led a fraud – the smallest fraud we studied – and two women with their husbands. One reason surely must be that women are not as often in positions to lead these schemes. However, even when we compared women and men in similar corporate positions, women were less likely to play leadership roles in the fraud. Is there a “glass ceiling” in the white-collar crime world?

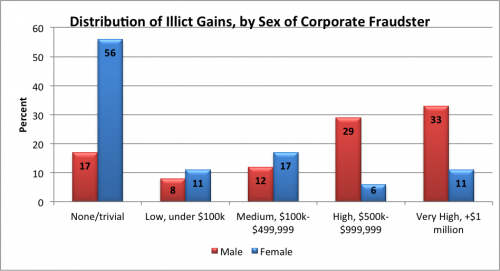

What most surprised me, however, was how little the women benefited from their illicit involvement. The wage gap in illicit corporate enterprise may be larger than in the legitimate job market. Over half the women did not financially gain at all whereas half the men pocketed half a million dollars or more. The difference in illicit-gains persisted even if we compared women to their co-conspirators. Males profited much more. Women identified “gains” such as keeping one’s job.

Even when women are in the positions to orchestrate these frauds, it’s likely that the men who initiate these conspiracies prefer to bypass women, involving them in minor roles when need dictates or when trust develops through a close personal relationship. And women hardly initiated any schemes. Women business leaders tend to be more risk-averse and apt to stress social responsibility and equity, perhaps making corporate fraud unlikely.

So, would having more female leaders reduce corporate crime? We don’t know, but we think it’s likely. Women executives tend to make more ethical decisions, avoid excessive risk-taking, and create corporate cultures unsupportive of illegal business practices. Time will tell if, on the other hand, women moving up the corporate ladder increasingly adopt a wheeler-dealer, “dominance at all costs” corporate ethic.

Some may be a little disappointed that women either cannot yet or do not exercise their power over others to illegally advance their business (and personal) interests as men have been doing for generations. There are moments when I catch myself “rooting” for a more successful pink-collar offender – and examples exist. However, when I consider the destruction and havoc wrought on the U.S. economy and so many peoples’ lives by these financial crimes, I am reminded that this is not the way in which I hope women wield power when business leadership roles are more equally shared.

This posts originally appeared at the Gender & Society blog.

Jennifer Schwartz, PhD, is an associate professor of sociology at Washington State University. Her research focuses on the gender and race demographics of criminal offenders, violence, and substance abuse.