In 1985, Zeneca Pharmaceuticals (now AstraZeneca) declared October “National Breast Cancer Awareness Month.” Their original campaign promoted mammography screenings and self-breast exams, as well as aided fundraising efforts for breast cancer related research. The month continues with the same goals, and is still supported by AstraZeneca, in addition to many other organizations, most notably the American Cancer Society.

The now ubiquitous pink ribbons were pinned onto the cause, when the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation distributed them at a New York City fundraising event in 1991. The following year, 1.5 million Estée Lauder cosmetic customers received the promotional reminder, along with an informational card about breast self-exams. Although now a well-known symbol, the ribbons elide a less well-known history of Breast Cancer Awareness co-opting grassroots’ organizing and activism targeting women’s health and breast cancer prevention.

The “awareness” campaign also opened the floodgates for other companies to capitalize on the disease. For example, Avon, New Balance, and Yoplait have sold jewelry, athletic shoes, and yogurt, respectively, using the pink ribbon as a logo, while KitchenAid still markets a product line called “Cook for the Cure” that includes pink stand mixers, food processors, and cooking accessories, items which the company first started selling in 2001. Not to be left out, Smith and Wesson, Taurus, Federal, and Bersa, among other companies, have sold firearms with pink grips and/or finishing, pink gun-cases, and even pink ammo with the pink ribbon symbol emblazoned on the packaging. Because breast cancer can be promoted in corporate-friendly ways and lacks the stigma associated with other diseases, like HIV/AIDS, these companies and others, have been willing to endorse Breast Cancer Awareness Month and, in some cases, donate proceeds from their merchandise to support research affiliated with the disease.

Yet companies’ willingness to profit from the cause has also served to commodify breast cancer, and to support what sociologist Gayle Sulik calls “pink ribbon culture.” As Sulik notes, marking breast cancer with the color pink not only feminizes the disease, but also reinforces gendered expectations about how women are “supposed” to react to and cope with the illness, claims also corroborated by my own research on breast cancer support groups.

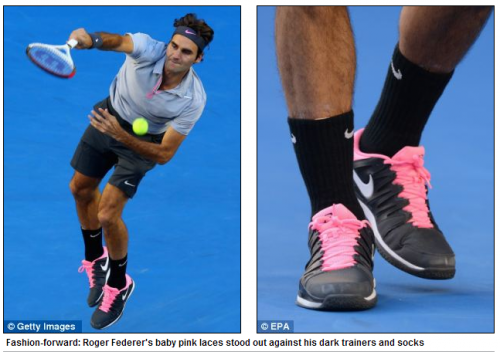

Based on participant observation of four support groups and in-depth interviews with participants, I have documented how breast cancer patients are expected to present a feminine self, and to also be positive and upbeat, despite the pain and suffering they endure as a result of being ill. The women in the study, for example, spent considerable time and attention on their physical appearance, working to present a traditionally feminine self, even while recovering from surgical procedures and debilitating therapies, such as chemotherapy and radiation. Similarly, members of the groups frequently joked about their bodies, especially in sexualized ways, making light of the physical disfigurement resulting from their disease. Like the compensatory femininity in which they engaged, laughing about their plight seemed to assuage some of the emotional pain that they experienced. However, the coping strategies reinforced traditional standards of beauty and also prevented members of the groups from expressing anger or bitterness, feelings that would have been justifiable, but seen as (largely) culturally inappropriate because they were women.

Even when they recovered physically from the disease, the women were not immune to the effects of the “pink ribbon culture,” as other work from the study demonstrates. Many group participants, for instance, reported that friends and family were often less than sympathetic when they expressed uncertainty about the future and/or discontent about what they had been through. As “survivors,” they were expected to be strong, positive, and upbeat, not fearful or anxious, or too willing to complain about the aftermath of their disease. The women thus learned to cover their uncomfortable emotions with a veneer of strength and courage. This too helps to illustrate how the “pink ribbon culture,” which celebrates survivors and survivorhood, limits the range of emotions that women who have had breast cancer are able to express. It also demonstrates how the myopic focus on survivors detracts attention from the over 40,000 women who die from breast cancer each year in the United States, as well as from the environmental causes of the disease.

Such findings should give pause. If October is truly a time to bring awareness to breast cancer and the women affected by it, we need to acknowledge the pain and suffering associated with the disease and resist the “pink ribbon culture” that contributes to it.

Jacqueline Clark, PhD is an Associate Professor of Sociology and Chair of the Sociology and Anthropology Department at Ripon College. Her research focuses on inequalities, the sociology of health and illness, and the sociology of jobs, work, and organizations.