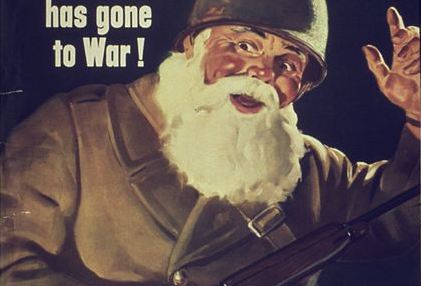

- Militarizing Santa: Then and Now (pictured)

- A Short History of Santa Claus

- Politics and the Rockefeller Center Christmas Tree

- The Pagan Roots of Christianity

Christmas Across Cultures

- Befana, the Christmas Witch

- Christmas Cultures

- Santa’s Evil Side Kick

- Black Pete (NSFW; trigger warning for images of blackface)

- Protestantizing Christmas Gift Giving: The ChristKind

- Snegurochka: Santa’s Granddaughter

- Global Christmas

- Culture and Coordinating Human Action

- Jewish Christmas — The Chinese Connection

The Economics of Christmas

- Disguising the Gift of Money

- International Comparison of Christmas Spending

- Christmas has an Economy

- The Christmas Tree Industry

- 1/3rd of People Say Commercialism is the Worst Part of Christmas

Racializing Christmas

- Racism and Xenophobia in “War on Christmas” Rhetoric

- White Privilege and the Snow White Santa

- New York Times Gift Guide for People of Color

- Black Pete (NSFW; trigger warning for images of blackface)

- Holiday in the Hood

- The Hazards of Historical Amnesia

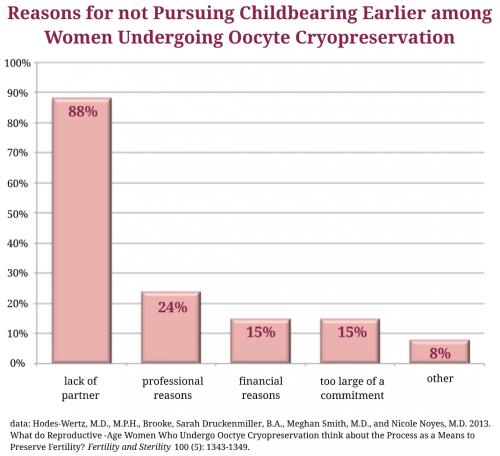

Christmas and Gender

- Gender-Swapping Christmas

- Mariah Carey’s “All I Want for Christmas is You”: 1994 versus 2011

- 12 “Mums” Makes the Workload Light

- Christmas is Women’s Work

- Tis the Season for Reinforcing Gender Differences

- Holidays: A Time for Men to Buy Themselves Stuff

- Christmas at the White House: A Role for the First Lady

Gift Guides and the Social Construction of Gender

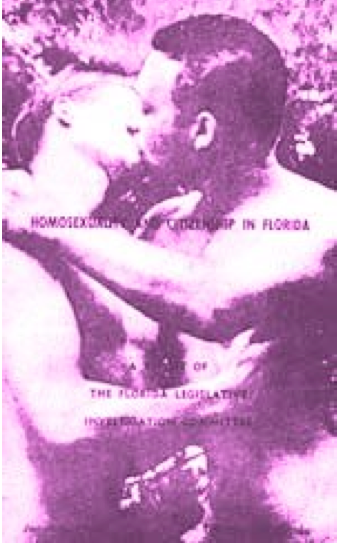

- The Heterosexual Gift Giving Imperative

- Gender, Technology, and Toys ‘R Us

- Gender in Toy Catalogs

- Body Messages in Christmas-Themed Ads

- Gift Giving with Gender Stereotypes

- More Gender Gift Giving and Advertising

- Another Gendered Gift Guide

- And more Gendered Gift Guides

- And more Gendered Gift Guides!

- Or, you could just buy her a clothesline

Sexifiying Christmas

Christmas Marketing

- Support the Troops. Shop Walmart?

- Fun with the 2009 Target Catalog

- Guns for Christmas

- A Shorty History of Santa Claus

- 1930s Ad Touting Razor Technology

- Gap Thinks Girls are Vapid

On Discourse:

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.