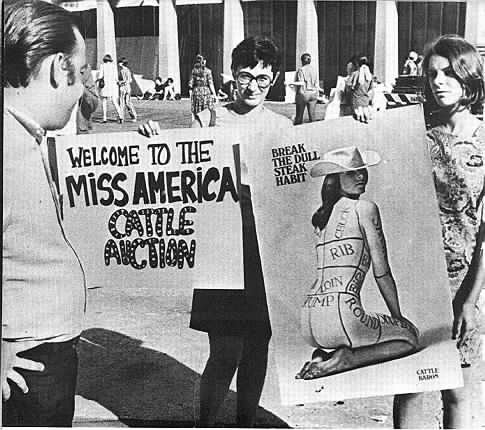

Iconic images — such as a single student standing stoic before Red Army tanks in Tiananmen Square, a protester leaning forward to put a flower into the barrel of a soldier’s gun, or two African-American athletes raising black-gloved fists on the Olympic victory podium — often seem to shape much of what we “know” about various historical events or social movements. In our social media, mass culture world, images and interpretations spread fast. But where do these images come from? How and by whom are they produced?

Last week, wire services photographer Noah Berger found himself behind the lens of a photograph that has the potential to become such an image. In it, a white, plain-clothes police officer in Oakland, CA, aims his gun at protesters and reporters, while his black partner holds down a black protester. At a historical moment when protests are sweeping the country, bringing issues of police violence and the unequal treatment of minorities into public consciousness with slogans like “Black Lives Matter,” it is perhaps not surprising that the photo seems to have gone viral.

Sociologist Joshua Page reached out to Berger to discuss the photographer’s experience in creating this powerful image. In an interview, the two talked about the social logistics of photographing protests, the life of a “stringer,” and the struggle to capture the essence—even the sociological significance—of events that have complex backstories and often conflicting meanings in single, silent photographs.

1. The Photo.

Page: Why was the police officer pointing his gun at people?

Berger: In basic, loose terms, what happened on the night that the plain-clothes officer pulled his gun on the protesters began with protests on the Berkeley campus, about 7:00pm. They disrupted a lecture by, I think, one of the founders of Paypal, but they marched peacefully for a couple of hours. It was about 150 people, and they marched all the way from the Berkeley campus to downtown Oakland—about three miles.

When it reached downtown Oakland, at 14th and Broadway, which is sort of “protest central,” it started getting a little bit edgier. You could just feel it in the crowd… Pretty soon after that, the first window got smashed. Then the cell phone store got looted. I watched that happen. I couldn’t take any pictures, but I did watch it.

So, the protesters kept marching, banging on windows. There was some minor vandalism, and, according to the California Highway Patrol [CHP], when the cell phone store was looted, that was when two officers who had been in a car behind the protest group got out and started walking with the group. This is all according to the CHP.

I noticed the officers in the crowd, and I actually thought they looked kind of scary. I made a mental note to stay away from them. They didn’t strike me as cops, they just looked kind of scary. But as far as I saw, they just walked along with the crowd. There have been some reports of them doing other things… but all I saw them doing was walking along with the group.

About 20 to 30 minutes after the first vandalism started, a group of roughly 60 people were walking, and someone just turned on these two guys and started yelling that they were cops. Kind of taunting them. More people joined in. At that point, the San Francisco Chronicle photographer tells me, somebody ran up behind the cops and pulled the hat off one of the guys, threw it on the ground. Apparently another person hit one of the officers on the back of the head. This is according to the Chronicle.

At that point, one of the officers in the crowd and a guy just started scuffling. It just turned into a brawl, and the crowd started advancing on these two officers. At that point, one of the officers pulled out a baton, which you can see in some of the pictures, and he also pulled out his firearm. He kind of aimed at the crowd and swung it around, saying something to the effect of, “Stay back! Back off.” He held them off for about 30 seconds until the regular, uniformed officers swooped in from the end of the block. They formed a protective semi-circle around these two guys and the protesters they were detaining, and pushed the other protesters backwards to secure the area.

Page: At what point did he point the gun at the Chronicle’s photographer?

Berger: I very much doubt that the cop knew the guy was press and was specifically pointing at him. He was holding the crowd back. It was more general, to everybody, “Stay back.” And in the picture, his hand isn’t on the trigger. So, I don’t think he was specifically targeting the press. It was just that we were close to him.

Page: Have you been surprised at how widely that image has been circulated and the ways people have interpreted it on Facebook and elsewhere?

Berger: Very much so. Michael Short, the Chronicle photographer and I, when we talked about it right after it happened, we thought the story was gonna be, “How crazy is this that a group of protesters knowingly attacked undercover officers?” That’s what we thought was the amazing part of the moment!

But after that picture came out, it conveyed a different perspective: “How crazy is it that this undercover cop would pull his weapon on protesters?” It’s a really good case of the picture not showing the whole story. It’s not a lie. It definitely is part of the story, but it’s not the whole occurrence.

It’s led to a cascade of interest that I’ve never really seen before, which was weird and mostly good. Not all good, but mostly good.

2. The job.

Page: So, what is your job title?

Berger: I’m a freelance photographer, a “stringer.”

Page: Do you see yourself as a photojournalist?

Berger: Yeah, I kind of wear two hats. It changes depending on the season, but I spend about 60% of my time on the news and about 40% in corporate or government work. But when I’m out during the protests, I certainly consider myself a photojournalist.

Page: Are there particular assignments you like to take?

Berger: Definitely the protests, the edgier protests are high on my list. That, and wildfires. My favorite assignments are protests and wildfires.

The King Wildfire, 2014. © Noah Berger

The King Wildfire, 2014. © Noah Berger

Page: What is it you like about them?

Berger: The wildfires are great, because you’re in these volatile, somewhat dangerous situations, but no one’s aiming for you, unlike in the protests. You’re out in the woods, trying to get your shot, and you’re not dealing with the public relations side or negotiating society. You’re just on your own.

The protests, it’s just interesting to see when there are clashes and when the emotions and violence flare up. And on another side, it’s just interesting to see that side of life. It’s something a lot of people don’t witness.

Page: Are there particular types of images you’re looking for when shooting a protest?

Berger: Sure. Working for the wire services like the AP or Reuters, I try to keep in mind one image that sums up an event. I’m not just looking for one image from the night, but I like my images to say something. When you’re working for a wire service, it’s more important to consider an audience outside the local area and know that you’re looking for images that sum up the event.

Page: Those tend to be more dramatic images.

Berger: “Dramatic,” like for the police protests, obviously would be something that might have a policeman and a protester in it, and some interaction. But it doesn’t need to be. Reuters, another photographer, got a shot of this guy with fire around him and a sign that said “Black Lives Matter.” There’s no other context, but it just had a great feeling. So it doesn’t need to be both sides, but I think the photo needs to speak to the whole issue.

Page: How do you know when the picture represents what’s going on?

Berger: You just kind of know when it happens, I guess…

Page: Another shot you had the other day, of the freeway stopped in both directions, was just amazing.

Berger: That’s actually a little different than I normally shoot; it doesn’t tell the story as quickly as the images I would normally look for. It took me longer to warm to that photo, because it was harder to “read.” You need more context [to know that these are protesters stopping traffic on a freeway].

Page: What’s your process for shooting a protest? How do you know where to go?

Berger: Well, there are a couple different ways. To find out where the protest is gonna be, there’s a website that lists the bigger ones. Twitter has become huge. A lot of these protests are just organized a couple hours before by someone saying, “Hey, let’s meet at 7:00 at the corner of _______ and _______,” and that just creates the protest. So, Twitter’s good.

I also use a police scanner, and I’ll have that on, depending on what the protest is. Like, if there are multiple protest groups roaming the streets, that’s really useful…. The other way is following, if there are multiple groups, following where the police helicopters are. You can look up and kind of figure that out. But the scanner’s a really useful tool.

3. Interactions: Protesters, Police, and the Press Corps.

Page: Do you ever get pushback from protesters, get hassled?

Berger: All the time. When I’m out there, my primary concerns are staying safe from protesters, staying safe from the police projectiles or clubs, and just keeping my gear safe.

Page: I’m sure there must be times when the idea of a protest is to get the images out there and spread the word. Are there times when your relationship with the protesters is more collaborative than antagonistic?

Berger: It’s not necessarily true, actually, that they want the word out. There’s definitely a large group that does want the world to know what’s going on here… but a lot of people seem to want to be out there pushing the boundaries of police and society and don’t want it documented.

Page: Is there a sense in some protests that the press is part of the “system” people are protesting to begin with?

4. Framing and Representation.

Page: Do you think about potential public or political reactions to the images when you’re shooting them?

Berger: Yeah. And I have a strong belief that we’re showing the world what’s happening in any given situation. I mean, that moment with the handgun coming up, you’re not gonna see that otherwise. There were, plus or minus, three mainstream journalists there, and we’re really the eyes of “truth” in the bigger, somewhat objective reality that’s being conveyed to the world.

Page: Do you think about how certain images would support particular narratives?

Berger: Sure. I think there’s an inherent bias toward, in protests, the sparky, edgy action shot. It’s not because we want to show protesters [as violent], but it makes for more dramatic pictures… I don’t ever go into it going, “I’m gonna take a shot that makes this side look like this,” but sometimes when you’re editing, you can see that. “Oh, this shot really conveys this.”

Page: You’re aware that certain images support certain perspectives, and recognize that sometimes you’re emphasizing the edgier side of a protest when a lot of it is peaceful. Like you were saying, all the way from Berkeley to downtown Oakland…

Berger: I am very conscious of that: one image can convey something that isn’t the whole truth. I try, when I write my caption, to reflect that. When I covered Occupy, if there was a protest where 1,500 people shut down a port and then 100 people broke windows, in my caption I’d say, “After a largely peaceful protest of 1,500 people…” There is definitely a responsibility beyond the image.

Page: So, what is your view of the current wave of protests? Do you think they’re effective? Justified?

Berger: I definitely don’t feel comfortable speaking to whether they’re justified… I don’t think any mainstream journalist trying to report from an objective position should put out their opinion on an issue they’re covering…. Our job is to stay, to try to stay as objective and neutral and balanced as we can. Telling our opinion would fall outside those boundaries, so it’s not something I’m comfortable talking about. …You could definitely be looking at a group on any side of an issue and think… “That’s kind of wacky,” but it’s still your job to stay objective and present all sides to an issue.

5. Letting Go.

Page: It must be really interesting to shoot the images, put them out there, and see how people respond to them and use them. I’ve seen this undercover cop photo turned into a meme. Do you pay attention to how they get written up and used?

Berger: On this story, I have been, definitely, but not always. I mean, there are all kinds of ironic things. This one was used as a protest poster for this coming weekend’s protest. I’m sure some of the people, maybe even the people designing the poster, are gonna be out there blocking my camera! Usually, the photos just sort of go off into the media world, and they’re gone for me.

Joshua Page, PhD, is a professor of sociology at the University of Minnesota, where he specializes in crime and deviance. He is the author of The Toughest Beat: Politics, Punishment, and the Prison Officers Union in California. This post originally appeared at The Society Pages.