The geographic span of the Holocaust was one of the most pivotal elements of the genocide. The extreme lengths that the Nazis took to displace many of their victims demonstrates their dedication to ethnic cleansing, enslavement, and ultimately the eradication of entire societies.

In Professor Sheer Ganor’s course “History of the Holocaust,” students’ final projects were designed with three core goals: to highlight the spatial dimension of the Holocaust, to give students an opportunity to intimately learn individuals’ life stories, and to analyze primary sources and scholarly studies that shed further light on survivors’ stories.

The students used StoryMaps, a digital platform intended for telling spatial stories. “[Story maps generally] use geography as a means of organizing and presenting information,” says Shana Crosson, Academic Technology Consultant in the College of Liberal Arts, who worked with Professor Ganor to implement this technology in her course. “In some classes, students create spatial data by closely evaluating primary sources such as newspapers, oral histories, archival records, guide books, or even phone books. This information may be combined with other databases and information to create maps, and ultimately, combined with narrative in a story map.”

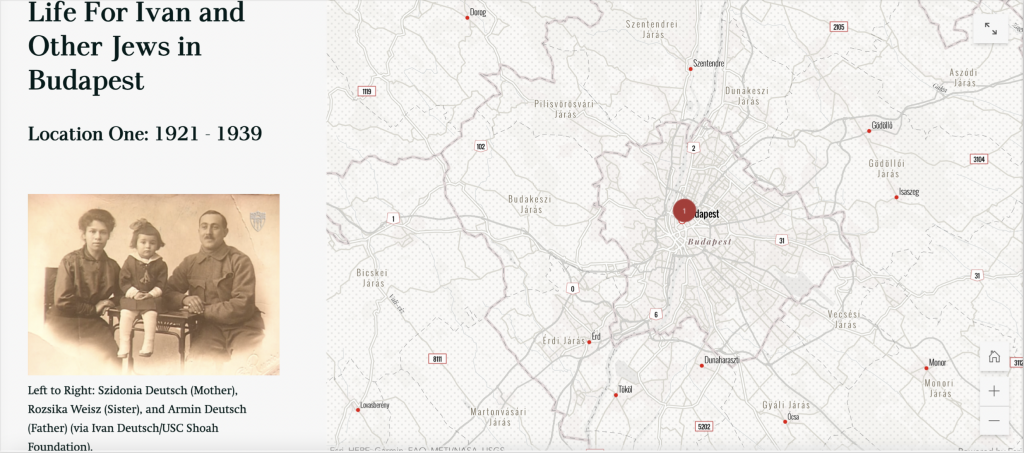

Survivors, as students learned, were torn from their hometowns, dislocated multiple times — often through several ghettos and camps — and left to search for a new home after the war’s end. As a result, mapping the paths of different individuals illuminated the Holocaust as a global event and showed how the genocide’s far-reaching effects extended across borders and continents.

Though millions of people fell victim to the Nazis’ genocidal machine, each person’s experience was unique. By closely studying a single survivor, students developed a sense of familiarity with that person and the details of their biography — from their childhood memories to strategies of processing trauma. Video testimony also increased this familiarity, as students learned to recognize the survivor’s voice, understand their accent, and pay attention to their body language.

This spatial visualization not only highlighted the centrality of forced removal in the execution of this crime; using story maps, students also embedded the events recounted by survivors into a broader history of the Holocaust and the Second World War. Students took the maps and spatial data they created and then communicated their understanding of events by combining textual narratives, maps, and other visuals.

The audience for these projects often extends beyond the course instructor, which gives them a different impact than a mere term paper. Students not only create a usable resource when compiling the data themselves; by defining structural parameters themselves (i.e., when students act as the mapmakers), they understand how mapping is left to subjective interpretations.

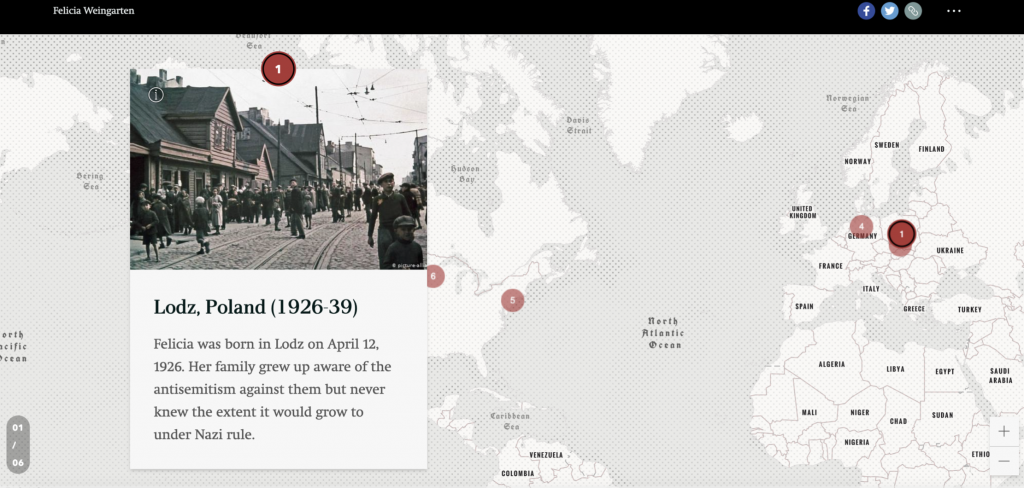

As Crosson also noted, feedback from students has been quite positive. Kyli Knutson, one of the students in Professor Ganor’s course, said, “I think what struck me the most about this project while working on it was just how close I felt to [Felicia Weingarten] after completing it. Even though I had never met [Weingarten], I learned so much about her life and her personality, that I felt like I had met her.” Knutson’s comments echo what many students said: they learned new skills, including learning a new technology, presenting information in a different format, and how to build maps.

Knutson enjoyed the opportunity to do something creative with story maps that also addressed challenging topics such as the Holocaust. “It was hard for me at first to figure out how to structure the Storymap because the question was: how do you compile someone’s whole life in a way that does justice to their story while also educating others? The story maps helped combine [Weingarten’s] life story, the educational importance of her story, and relevant secondary sources.”

Knutson’s subject, Felicia Weingarten, was born in Łódź in 1926. Weingarten has been a consultant for the University of Minnesota in the past and has served as a resource for interviews and panel discussions on television and radio, as well as for newspapers and books. She has spoken extensively with high school and college students on topics dealing with the historical, psychological, and political factors of the Holocaust. In 2005, her book “Ave Maria in Auschwitz: A True Story of a Jewish Girl From Poland” was published by DeForest Press. The book is a collection of short stories that poetically reflect her experience in the ghettos and camps during the Holocaust.

Some students even traced the paths of survivors who settled in the Twin Cities and whose materials are part of the Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies’ permanent collections. Felicia Weingarten’s book and other materials are available through the Center’s collections. Her testimony is available at the University of Minnesota through CHGS (via Elevator), the Visual History Archive, developed by the USC Shoah Foundation Institute for Visual History and Education. Since its founding, CHGS has maintained and curated its own collections, which are accessible to UMN faculty, students, and staff as well as the general public.

Taylor Johnon, an MFA Candidate in Art at the University of Minnesota, along with Jennifer Hammer, began in earnest to reorganize the Center’s Elevator site to make it more user-friendly. Since last spring, CHGS staff have begun creating new search parameters and organizational practices. CHGS hopes that, with an Elevator interface that is easier to use, more faculty and students will use the Center’s digital resources.

Sheer Ganor is an assistant professor of history at the University of Minnesota. A historian of German-speaking Jewry and modern Germany, her work focuses on the nexus of forced migration, memory, and cultural identities.

Shana Crosson is the academic technology consultant at the University of Minnesota’s College of Liberal Arts. She currently helps integrate Geographic Information Systems in a variety of disciplines in K12 and Higher Education, including History, Sociology, and Foreign Languages.

Kyli Knutson is a junior History major at the University of Minnesota – Twin Cities. She has always been interested in history. Her undergraduate coursework has allowed her to pose important questions about historical events and figures, as was the case with her Storymaps project. In addition to her interest in History, she plans to double major in Art History and graduate in the spring of 2022.

Meyer Weinshel is a Ph.D. candidate in Germanic studies at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities. He is a research assistant and the educational outreach coordinator for the UMN Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies. He has taught community Yiddish classes with Minneapolis-based Jewish Community Action and will be a lecturer of Yiddish studies at the Ohio State University in 2021.

Comments