In early March, 10-year-old Ariana Mangolamara committed suicide in the Aboriginal community of Looma in Western Australia. Her death wasn’t unique: she wasn’t the first in her community or even her family to commit suicide. However, her story gripped international headlines and prompted a soul-searching analysis of why the plight of Australia’s indigenous peoples is worse than ever, despite formal political recognition and efforts to help. Many of these efforts seem designed to destabilize Aboriginal communities through systematic neglect, the breaking of families through child removal and a callous disregard for culturally viable strategies.

The fact is that Australia has a staggering 15,000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in out-of-home care, making them nine times more likely to be removed from their homes than non-indigenous children. By contrast the Stolen Generations, who were removed and forcibly assimilated into settler society from the 1930’s to the 1960’s, only claimed around 10,500 children. Historically, Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders have been subjected to genocide and many groups have been completely destroyed, including the entire native population of Tasmania. Activists have had good reason to advocate that the genocide continues through child removal and systematic neglect of indigenous communities.

While the child’s safety is often a legitimate concern, lack of cultural sensitivity and outright racism also play a role. Child removal is often the first action taken when a problem is discovered and families rarely receive other help or a chance to regain custody. Radically different cultural practices in child-rearing are often misinterpreted as neglectful by western criteria. Indigenous Australians were among the most dehumanized and persecuted ethnic groups in the British Empire. Open racism is still prevalent today, especially in rural areas where Aboriginal populations are most concentrated. As late as the 1980’s, prominent Australians were on TV promoting mass sterilization of Aborigines who refused to be assimilated into mainstream society.

Although Ariana had been removed from her home, she was one of the 67% of children who were placed with relatives or in other Aboriginal homes. The initiative to keep removed children as close to their family and culture as possible was spear-headed by Grandmothers Against Removals, an activist group made up of survivors of the Stolen Generations dedicated to keeping the current ‘stolen generation’ from happening. Keeping removed children within context of their culture has been shown to improve their ability to recover from the trauma of dislocation, but their new communities often lack even basic mental health services. Even though Ariana displayed symptoms of depression and it was known that her 12-year-old sister had committed suicide before she was removed, no professional help was given to her. The remoteness and lack of infrastructure in many Aboriginal communities is a prime reason for the sharp rise in suicides among young people in the last 20 years. Suicide rates have corresponded with the spike in child removals which has itself inhibited efforts to resolve prevalent social problems within indigenous communities.

A survey of Ariana’s community found that 17% of the men were convicted sex offenders. Her father had been incarcerated for domestic assault on her mother. Aboriginal women are 35 times more likely to be hospitalized for assault than non-Aboriginal women and 11 times more likely to be killed. Alcohol and other chemical substitutes for hope ran rampant through her community. Kids have been seen playing with nooses and heard talking about death and suicide, and there is no wonder that the adult suicide rate is 4 to 5 times higher than among non-Aborigines. Despite lower rates of sexual abuse, Aboriginal children are twice as likely to contract an STD due to lack of access to healthcare. Although Ariana found a safe home with relatives, the accumulated harm of years of abuse, neglect and universal despair was not adequately addressed.

These issues have not been completely ignored by the government, though. After Prime Minister Kevin Rudd became the first leader to acknowledge and apologize to the Stolen Generation, he launched a “Closing the Gap” initiative in an effort to reduce inequality between Aboriginal and larger Australian populations. Goals such as reducing infant mortality and increasing literacy are currently on track, but employment and life expectancy gaps remain wide. A parallel “Close the Gap” public awareness campaign was launched by Aboriginal communities to voice their opinions and concerns on how the initiative should proceed. Despite this, cultural norms and differences between Aboriginal and Western societies have often been a hindrance to government initiatives. Indigenous communities rarely have a stake in proposed programs and local leaders are often over-ruled or ignored. A long and continuing trend of abuse and frustration have left many Aborigines mistrustful of government assistance.

Prejudice against native Australians remains strong, especially in the communities who have the closest and most direct impact on Aborigines. The devastation of their lifestyles and communities are as likely to be viewed with contempt as compassion. Until these attitudes are changed, efforts to “Close the Gap”, protect children and restore vitality to communities will continue to fall short.

Jamie Anderson is a senior at the University of Minnesota, majoring in Global Studies.

But the declaration of incompatibility of the “General Amnesty Act for the Consolidation of Peace” with the national and international corpus of law is not the only achievement in the quest of justice for the victims of the armed conflict. In that same judgment, El Salvador aligns itself with the current tradition in international law which establishes that war crimes and crimes against humanity are not bound by statutes of limitations. This decision also constitutes a breaking point with the national jurisprudence that had declared so far that the time to judge the international crimes committed during the civil war had passed by.

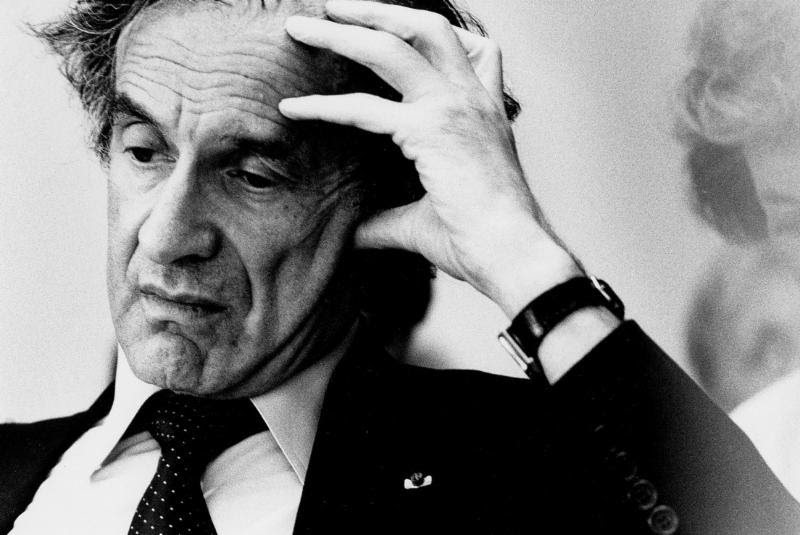

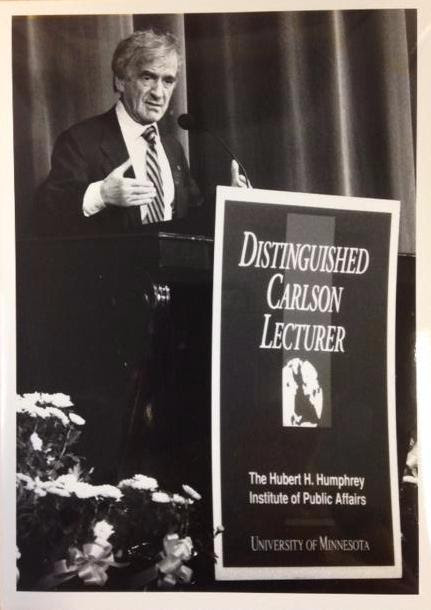

But the declaration of incompatibility of the “General Amnesty Act for the Consolidation of Peace” with the national and international corpus of law is not the only achievement in the quest of justice for the victims of the armed conflict. In that same judgment, El Salvador aligns itself with the current tradition in international law which establishes that war crimes and crimes against humanity are not bound by statutes of limitations. This decision also constitutes a breaking point with the national jurisprudence that had declared so far that the time to judge the international crimes committed during the civil war had passed by. There are many that contend today that the Holocaust’s global presence and iconic status obscures other forms of mass violence, and even the acknowledgment of other genocides. Elie Wiesel’s seminal role in Holocaust memorialization worldwide demonstrates exactly the opposite. The proliferation of Holocaust remembrance, education and research efforts has been extraordinarily influential in the moral and political debates about atrocities, and in raising the level of attention to past violence and responsiveness to present genocide and other forms of gross human rights violations.

There are many that contend today that the Holocaust’s global presence and iconic status obscures other forms of mass violence, and even the acknowledgment of other genocides. Elie Wiesel’s seminal role in Holocaust memorialization worldwide demonstrates exactly the opposite. The proliferation of Holocaust remembrance, education and research efforts has been extraordinarily influential in the moral and political debates about atrocities, and in raising the level of attention to past violence and responsiveness to present genocide and other forms of gross human rights violations. Elie Wiesel had a profound effect on my life. In 1997 I embarked on a journey to earn my Master’s degree from the University of Minnesota. At the time that I began my classes I had no thoughts of studying the Holocaust, but through a series of small events, I found myself thinking of nothing else. I do not remember when I read Night, nor do I recall what led me to return to Wiesel’s work while in graduate school. For some reason I turned to a little known collection of his short stories titled One Generation After, published in 1970. How the book found its way from my mother’s bookshelf to mine is not clear, but for some reason, I picked it up and read it. The story that changed my life was “The Watch.” Over the course of six pages, Wiesel tells of his return to his home of Sighet, Romania and the clandestine mission he undertakes to recover the watch given to him by his parents on the eve of his Bar Mitzvah. It is the last gift he received prior to being transported with his family to Auschwitz. Like many Jewish families, fearing the unknown and hoping for an eventual return, he buried it in the backyard of their home. Miraculously, he finds it, and quickly begins to dream of bringing it back to life. However, in the end he decides to put it back in its resting place. He hopes that some future child will dig it up and realize that once Jewish children had lived and sadly been robbed of their lives there. For Wiesel the town is no longer another town, it is the face of that watch.

Elie Wiesel had a profound effect on my life. In 1997 I embarked on a journey to earn my Master’s degree from the University of Minnesota. At the time that I began my classes I had no thoughts of studying the Holocaust, but through a series of small events, I found myself thinking of nothing else. I do not remember when I read Night, nor do I recall what led me to return to Wiesel’s work while in graduate school. For some reason I turned to a little known collection of his short stories titled One Generation After, published in 1970. How the book found its way from my mother’s bookshelf to mine is not clear, but for some reason, I picked it up and read it. The story that changed my life was “The Watch.” Over the course of six pages, Wiesel tells of his return to his home of Sighet, Romania and the clandestine mission he undertakes to recover the watch given to him by his parents on the eve of his Bar Mitzvah. It is the last gift he received prior to being transported with his family to Auschwitz. Like many Jewish families, fearing the unknown and hoping for an eventual return, he buried it in the backyard of their home. Miraculously, he finds it, and quickly begins to dream of bringing it back to life. However, in the end he decides to put it back in its resting place. He hopes that some future child will dig it up and realize that once Jewish children had lived and sadly been robbed of their lives there. For Wiesel the town is no longer another town, it is the face of that watch.

The

The