In March, Gender & Society published an article titled, Gender-Based Violence Against Men and Boys in Darfur: The Gender-Genocide Nexus. The paper, co-authored by Dr. Gabrielle Ferrales (Sociology, UMN), Dr. Hollie Nyseth-Brehm (Ohio State) and Suzy McElrath (Ph.D. Candidate, UMN), analyses gender-based violence against men and boys during mass atrocity. Demonstrating new theoretical connections between gender, violence, and hegemonic masculinity, this work significantly advances our understanding of how genocidal violence is gendered, but also more broadly how gender inequalities can be reproduced and maintained in diverse settings and social structures.

Gabrielle Ferrales, Professor in Sociology at the University of Minnesota

Wahutu Siguru: What was the motivation behind this paper?

Dr. Ferrales: Though scholars have debated how gender facilitates and patterns violence, what is gendered about gender-based violence in any context remains understudied. Along this line more specifically, there is insufficient empirical work on gender-based violence against men and boys during mass atrocity. Yet, a more inclusive approach provides an opportunity to test, evaluate, and refine existing theory.

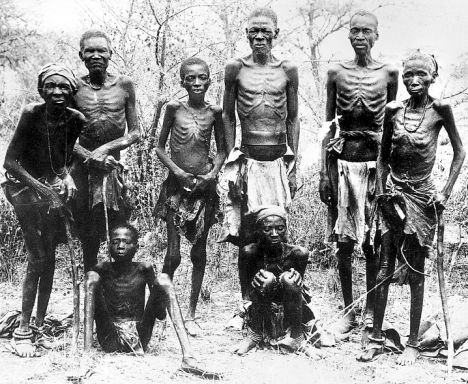

Current scholarship has also predominantly focused narrowly on rape by men against women. Yet, rape is but one form of gender-based violence perpetrated against men, boys, women, and girls during mass conflict. Drawing on the case of Darfur, we demonstrate how gender-based violence against men and boys constitutes an extensive range of physical and psychological actions, including acts of penetration, sexual assault, genital mutilation, forced nudity, culturally inappropriate actions that sexually harass or humiliate victims, as well as non-sexual acts perpetrated on the basis of gender, such as sex-selective killing. This expansive focus allows us to advance theoretical linkages between gender and genocide to illuminate why and how this violence occurs.

There appears to be a significant lack of scholarship on gendered violence against men during mass atrocity [your paper seems to add onto those by Charli Carpenter (2006) and Lisa Sharlach (1999)]. Why aren’t more scholars looking at this particular facet of mass atrocities?

This research is in its infancy and has faced several limitations, including limited sources of systematically collected data due to the underreporting of gender-based violence. This applies to victimization of men and boys, but also women and girls. Men specifically underreport due to shame and also significantly, their failure to conceptualize themselves as victims of gender-based violence. Work by professor Karen Weiss alerts us to the fact that when male victims do report gender-based violence, they frame their experiences in ways to reassert their masculinity, such as emphasizing how they vigorously fought back against their attacker. Similarly, international aid workers have lagged in recognizing men as victims, or potential victims, of forms of gender-based violence.

You state that both the body and gender become salient organizing principles of interaction. Would you expound on why and how?

This is a rather immense question, let me start with explaining why. Hegemonic masculinity or an emphasis on men’s physical strength, aggression, and sexuality patterns social interaction. It is omnipresent, not only in this context, but more broadly in social systems that construct men as heterosexual and dominant. Stated simply, specific norms about gender will pattern violence, where crime becomes a resource to invoke hyper-masculinity.

Gender-based violence manifests in multiple ways and contexts during mass atrocity. We identify a gender-genocide nexus where violence establishes, enforces, and reproduces gender-hierarchies within the broader social system. Candace West and Don Zimmerman originally coined the term doing gender illustrating how gender is a social construct or a product of social interaction between individuals, as well as social groups. In our case, we illustrate how dominant norms regarding gender influence forms of mass violence such as rape, genital mutilation and sex-selective killing. More specifically, doing gender through violence produces differences between groups along gender constructs that link heteronormativity, power, and ethnicity with the collective goal of eradicating the Darfuri enemy group. Specifically, we show how Darfuri men were systematically denied the attributes of dominant heterosexual masculinity and demarcated as outgroup members through four mechanisms of emasculation. Individual perpetrators, victims, and collective ethnic groups thus assume divergent yet interconnected roles of emasculators and emasculated. In this way, gender-based violence reaffirms the perpetrators own masculine dominance while simultaneously proclaiming power over the ethnic victim groups. Significantly, victimization of an individual is emblematic of the victimization of the entire community. Violence then is not only based on gender ideology but affects gender norms in cyclical, mutually reinforcing social processes that foster an exclusionary social order.

What, if any, was the most surprising finding for you as you wrote this paper?

How explicit norms regarding masculinity surfaced. For example, in one instance a perpetrator held a woman’s son hostage. He made her pay ransom in addition to forcing her to explicitly state that Arabs were the only “real” men. This strikingly illuminates how manhood is intimately linked with ethnicity. Another notable finding was the occurrence of post-mortem rape. This specific act not only emasculates the individual victim but brings shame to his family at large violating sacred burial norms and the victim’s standing in the afterlife.

What message do you hope the reader of this paper leaves with?

In order to theoretically advance our understandings of gender-based violence during mass atrocity, we need future research which examines the multiplicity of victimization of men, women, boys, and girls. While we caution that our findings reflect the Darfur case, they nevertheless highlight the importance of gendered analyses of mass violence and of uncovering the mechanisms through which gender inequalities are reproduced and become embedded in social structures. Specifically, we need more comparative work accounting for variation in extent and forms of gender-based violence across conflicts. There is also a need for both national and international courts to address both the scale and the nature of gender-based violence in mass atrocity.

Beyond this case, gender-based violence against men is not aberrant or confined to mass conflict but is prevalent in social systems that construct men as heterosexual and dominant. Gendered identities—typically masculine identities that emphasize strength, and courage—are privileged in settings ranging from the U.S. to Sudan. Following this line of inquiry, future research must further investigate how myriad forms of crime are linked to hegemonic masculinity.

Interview conducted by Wahutu Siguru, Ph.D. candidate in the University of Minnesota’s Sociology Department.

J. Siguru Wahutu was born and raised in Kenya and moved to Minneapolis to pursue his undergraduate education. He graduated from the University of Minnesota with a BA in Sociology and Global Studies and a minor in Cultural Studies. He stayed in Minnesota to obtain his PhD in Sociology with a thematic focus on genocide, media and collective memory and a regional focus on Africa. Wahutu is broadly interested in how news organizations and journalists in Africa produce knowledge about genocide and mass atrocity in neighboring African countries. He was the 2013-2014 and the 2015

J. Siguru Wahutu was born and raised in Kenya and moved to Minneapolis to pursue his undergraduate education. He graduated from the University of Minnesota with a BA in Sociology and Global Studies and a minor in Cultural Studies. He stayed in Minnesota to obtain his PhD in Sociology with a thematic focus on genocide, media and collective memory and a regional focus on Africa. Wahutu is broadly interested in how news organizations and journalists in Africa produce knowledge about genocide and mass atrocity in neighboring African countries. He was the 2013-2014 and the 2015

The semester is about to start and I find myself touching up syllabi and putting some order in my course material. While reviewing files, I came across a very helpful handout from a

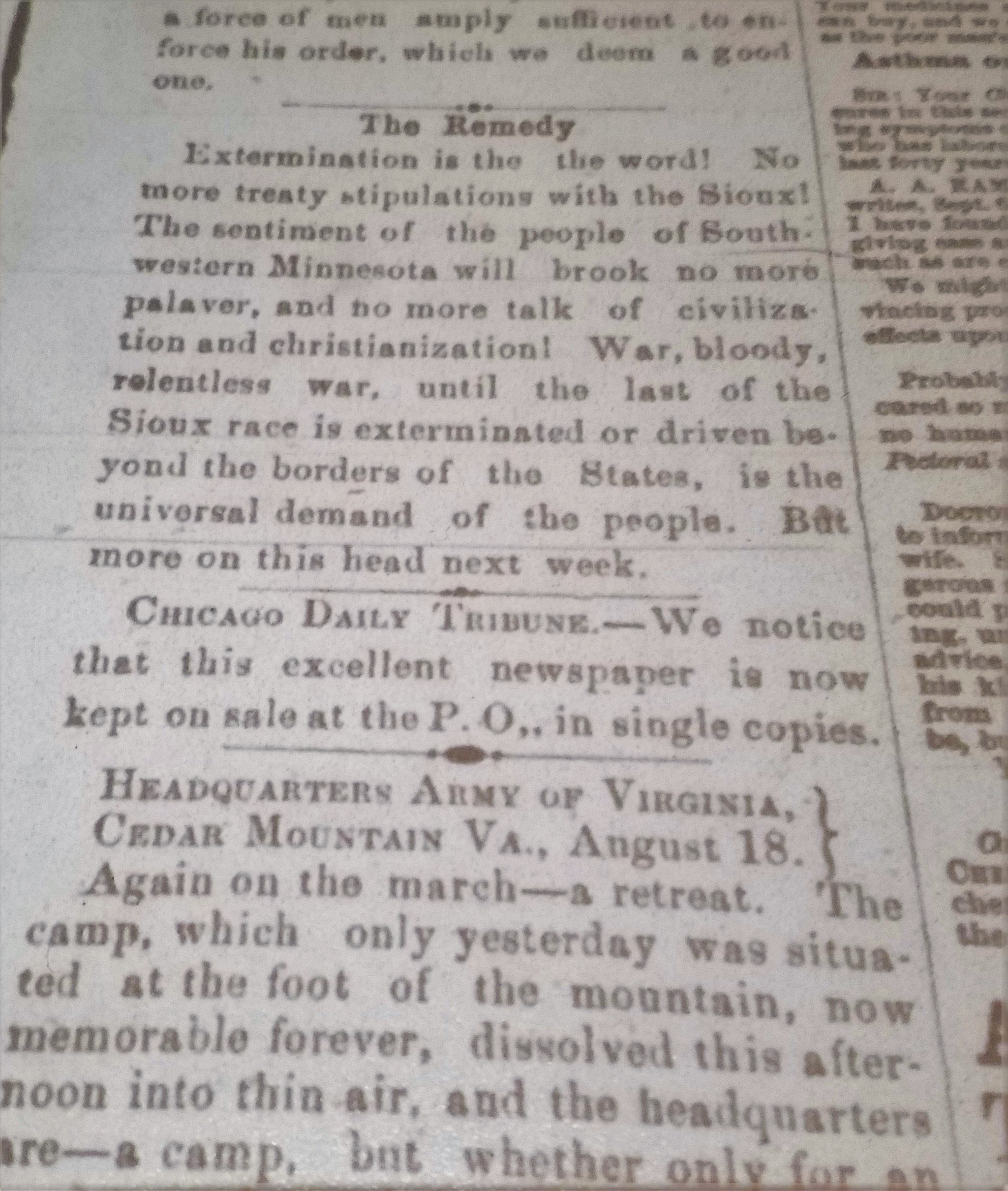

The semester is about to start and I find myself touching up syllabi and putting some order in my course material. While reviewing files, I came across a very helpful handout from a  The beauty of Discourse Analysis is that it helps explain what is underlying particular instances of speech, text or visual communication. It allows us to “distill” its essence and identify the patterns, rules, and structures of such expressions. Moreover, Discourse Analysis allows us to illuminate the relationship between specific language and its broader social and historical context. Forms of discourse have objectives, and follow strategies and devices to pursue these objectives. For instance, negative and positive atributions are stressed through the continued use of topoi and fallacies. In-groups and out-groups are constructed by membership categorization using literary devices like metaphors or synechdoches (in which a part represents the whole).

The beauty of Discourse Analysis is that it helps explain what is underlying particular instances of speech, text or visual communication. It allows us to “distill” its essence and identify the patterns, rules, and structures of such expressions. Moreover, Discourse Analysis allows us to illuminate the relationship between specific language and its broader social and historical context. Forms of discourse have objectives, and follow strategies and devices to pursue these objectives. For instance, negative and positive atributions are stressed through the continued use of topoi and fallacies. In-groups and out-groups are constructed by membership categorization using literary devices like metaphors or synechdoches (in which a part represents the whole).

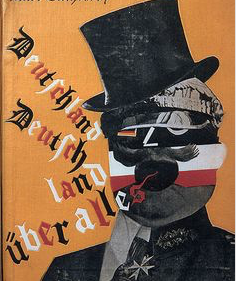

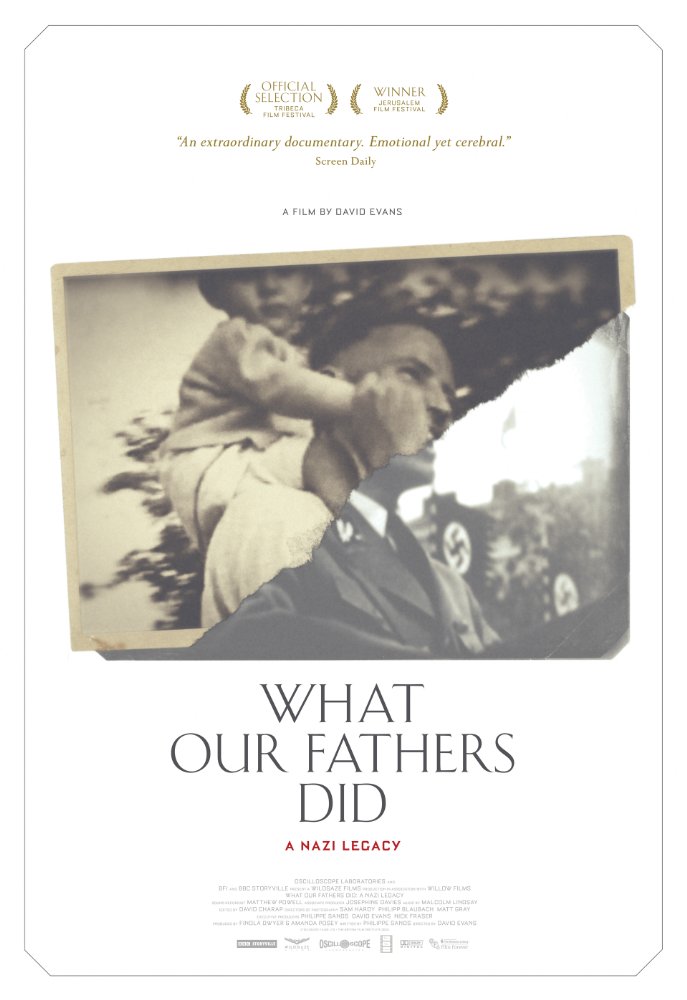

What Our Fathers Did: A Nazi Legacy

What Our Fathers Did: A Nazi Legacy