Most of our interactions with technology are rather mundane. We flip a light switch, buckle our seat belts, or place a phone call. We have a tacit knowledge of how these devices work. In other words, we have relatively standard, institutionalized, ways of interacting with familiar technologies. For example: if I were to drive someone else’s car, even if it is an unfamiliar model, I do not immediately consult the user manual. I look around for the familiar controls, maybe flick the blinkers on while the car is still in the drive way, and off I go. Removal of these technologies (or even significant alterations) can cause confusion. This is immediately evident if you are trying to meet a friend who does not own a cell phone. Typical conventions for finding the person in a crowded public space (“Yeah, I’m here. Near the stage? Yeah I see you waving.”) are not available to you. In years prior to widespread cell phone adoption, you might have made more detailed plans before heading out (“We’ll meet by the stage at 11PM.”) but now we work out the details on the fly. Operating cars and using cell phones are just a few mundane examples of how technologies shape social behavior beyond the actions needed to operate and maintain them. The widespread adoption of technologies, and the decisions by individual groups to utilize technologies can have a profound impact on the social order of communities. This second part of the Tactical Survey will help academics, activists, and activist academics assess the roll of information technology in a movement and make better decisions on when and how to use tools like social media, live video, and other forms of computer-mediated communication.

“The Master’s Tools” or, The Apparent Hypocrisy of Apple Computers in Zuccotti Park

Skeptical journalists and talking heads were quick to point out an apparent hypocrisy within the Occupy Wall Street movement. How can these hippies protest corporations when they are using Apple computers? The earliest of these pronouncements came from a New York Times piece that ended with:

One day, a trader on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange, Adam Sarzen, a decade or so older than many of the protesters, came to Zuccotti Park seemingly just to shake his head. “Look at these kids, sitting here with their Apple computers,” he said. “Apple, one of the biggest monopolies in the world. It trades at $400 a share. Do they even know that?”

These sorts of observations are usually left unchallenged. Eric Randall, writing in The Atlantic, noticed this trend and wrote:

Depicting protestors sitting on their MacBooks fits in with the broader narrative the media has settled on, one that depicts a disorganized group of well-educated college grads who can’t figure out how to stay on message. The MacBook seems always to be used as a sort of tongue-in-cheek “stuff white people like” condemnation of the jobless, disenfranchised protestors who can somehow swing a $1,300 computer.

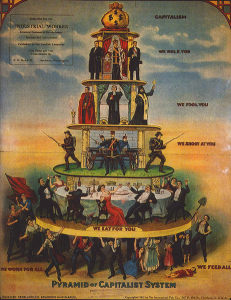

This is nothing new. Ever since the “Battle for Seattle” Western news outlets have used this particular narrative to discredit activists and reasserts the legitimacy of status quo consumerism. Sociologist Richard J.F. Day comments on this rhetorical device in his book Gramsci is Dead: “This is an extremely common trope of exclusion by inclusion, which works by trying to show that They (anarchist activists) are no less tainted with the stain of capitalist individualism than We (good capitalist citizens) are, and therefore have no right to criticize the status quo.”

Members of OWS have responded to these sorts of accusations, but (predictably) little has changed. Randall quotes the occupywallst.org blog‘s response:

This is a specious argument, that if taken to its conclusion would preclude the use of any product to those angered by the injustice of its producer. If you disagree with the policy of GE’s board, you cannot own a refrigerator, if a major paper conglomerate cooks its books you may not use toilet paper. This protest is against injustice committed by the greedy, not commerce itself or the products of corporations.

This appears to be an intractable problem. The powerful get to where they are by making lots of people need (and therefore buy) their stuff. They become an obligatory point of passage. An alternative is to engage in “lifestyle politics” and avoid the use of technologies that are incompatible with your politics. This, however, usually means you are spending considerable time and effort building new capacities from the ground up, and not using your energy and resources to actually fight what you see as wrong in the world. To the extent that fighting for change and building alternative capacities are mutually exclusive tactics, a collective must make a decision on time horizons and overall goals. In a pluralist social movement like #OWS, there is enough capacity to do both. Some can fight with the problematic tools that are currently available (e.g. Apple computers and Twitter) while others work on new technologies that are less connected to the corporations.

Tactic 3: Pluralist movements must recognize the failures of the existing sociotechnical social order, while also developing alternative capacities. Using computers made in sweatshops and for-profit social networking sites that have dangerous privacy policies are a necessity for effective augmented activism in the short term. Sustained, long term actions should also be working towards alternatives to these technologies.Building Alternative Capacity

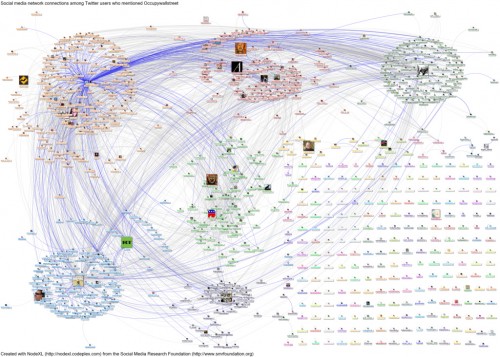

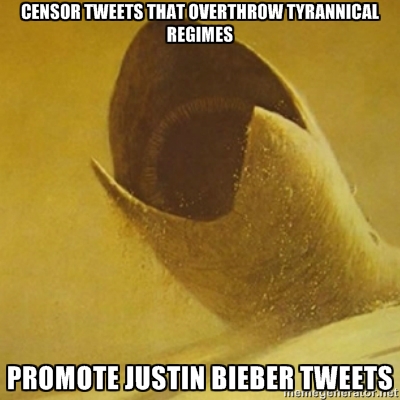

Since the eviction of almost every physical occupation in the United States, occupiers (especially the geeky ones) have been hard at work finding new and inventive ways of coordinating and connecting. One of these efforts is TheGlobalSquare.org– a multilingual, open-source social networking platform that would offer a “platform for the movement.” The media has already billed the project as “Occupy Wall Street Builds Facebook Alternative” but that only tells half the story. Building an alternative to Facebook also means building an alternative set of behaviors. Services like Twitter and Facebook are built with a certain kind of user in mind. They can be used for activism, but they are built for monetizing social activity. This means identity-protecting pseudonyms are forbidden, and censorship is negotiable.

Social media technologies are built with equal parts computer code and social norms. The assumed relationship of the individual to the collective is built into the system. For Facebook that means being open to everyone. Its institutionalized through and by the default settings of your account and the corporate business model. For Twitter, it means talk and connect as much as possible, but within the bounds and abilities of state authorities to suppress free speech on the web. Global Square’s stated philosophy is (in part):

The Global Square recognizes the principles of personal privacy as a basic right of individuals and transparency to all users as an obligation for public systems. While User Profiles will allow for as much privacy as the individual desires (technology permitting), Squares, Events, and Task Groups must be, at minimum, completely transparent to their user groups, and Systems must be completely transparent for full auditing capability by all Users.

Here, again, we see the delicate interplay of transparency and privacy that characterizes Occupy Wall Street. For Global Square, privacy of the individual is paramount, but that privacy is nested within two levels of transparency- transparency of collectives to its constituent individuals, and global transparency of governing sociotechnical systems to all users. Chris Kelty used the term recursive publics in his book Two Bits to describe communities of open-source coders that develop platforms that allow for and sustain the community. Global Square represents a similar social recursion: it is a platform to build capacity for new platforms of capacity building.

Tactic 4: Corporate-owned social media tools are not politically ambivalent. Technologies have embedded within them, assumed relationships and social organizations. Activists taking advantage of social media must recognize the subtle influences these technologies have on social action. If possible, new capacities for augmented activism must be built and maintained.Coda

Granted, the recursion can only go so deep. The code for Facebook or Global Square still run on the problematic hardware part 2 opened up with. The construction of open source hardware is much more complicated and resource intensive. This begs the question: Is it possible to have widely available digital technology in a world without exploited labor? Are the rare earth metals in our smart phones counter-revolutionary? What would a socially just version of Moore’s Law look like? These are questions left to future posts and other authors. What activists can and must do now, is enroll the expertise of engineers and scientist to explore these questions. This might mean activists learning the skills of engineering and science, but it might also mean creating a revolutionary computer science. Creating a computer for the people will be no easy task, and might mean creating a totally new technical artifact. It may also mean redefining technological progress to include lateral shifts that produce similar computational power but in more socially just ways. It is not enough to use these tools for good, we have to make new tools that are good.

Twitter’s new policy has been discussed by a variety of sources, but two authors –

Twitter’s new policy has been discussed by a variety of sources, but two authors –